Courtesy Urban Oasis

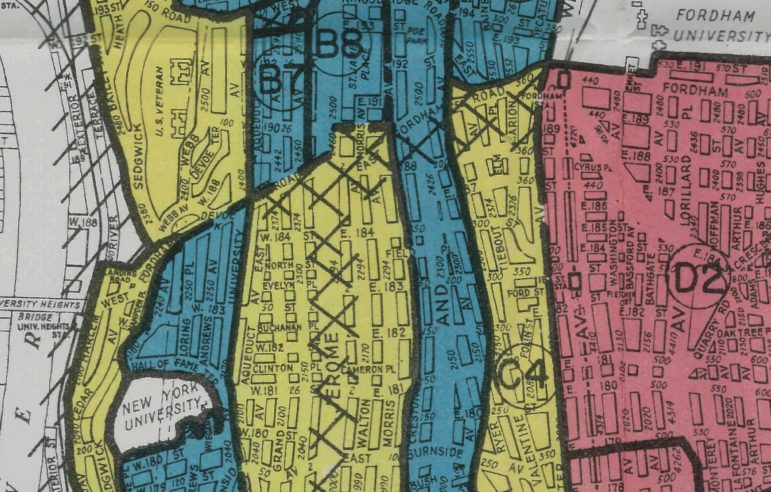

A section from a Home Owner's Loan Corporation map of the Bronx. Green was good (white). Yellow was iffy (mixed). Red was a place to avoid.

A cascade of crises is forcing America to confront the racism of its past and present—from overt acts of hate to subtler injustices that shape our society. Over 17 weeks, City Limits and Enterprise Community Partners will feature prominent New Yorkers’ views on how race and housing policy intersect to create a legacy each of us must confront, and the way forward we should take together. These are not necessarily views we endorse. But they are views we fully believe are important to share with each other. Here is the 15th post in our series. Read the rest here.

The city as we see it today did not happen by accident, but has been shaped and designed by policy, investment and intentions that predate most of us. To transform places for the better, these structures must be “undesigned” and their effects repaired. Undesigning systems and structures requires different thinking and creative innovation, both grounded in a deeper understanding of our shared history.

Much of the underlying fabric and identity of our nation was redesigned during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The absence of a social safety-net in such an economic crisis led to new policies of mass social uplift under Franklin Roosevelt, a progressive New York Democrat. Roosevelt’s New Deal for America, however, was heavily tainted by the Democratic Majority in Congress, based firmly in the South during the explicitly racist Jim Crow era.

Safety-net programs such as Social Security and Unemployment Insurance would exclude the vast majority of Black Southerners (and many poor Whites as well) by exempting agricultural and domestic workers from the benefit programs. New Deal housing policies in the late 1930s followed suit through the implementation of what would become known as “Redlining” maps.

Amongst other factors, maps created by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation gauged risk in the real estate market based primarily on racial “infiltration.” Neighborhoods in 239 cities and counties across the United States were each assigned a color. Green areas were considered optimal for investment while blue neighborhoods were almost as good. Yellow neighborhoods were considered third rate and expected to continue their decline. Finally, the red areas were deemed “hazardous” and cut off from investment.

In the corresponding Area Descriptions that explained the rationale for each color assignment, surveyors were explicitly instructed to look at factors such as “infiltrations of lower grade populations or different racial groups.” Redlined areas almost always included some degree of “Negro Infiltration” and were at times noted for their “obsolete homes”.

These government maps and the similar policies of the Federal Housing Administration significantly bolstered and expanded practices such as racial zoning and restrictive covenants, cutting communities of color off from mortgages, stable housing, and wealth creation for decades. This disinvestment in people has limited their potential and curtailed the contributions they have made to their families and society as a whole.

In the decades to follow, Redlined areas were more likely to be declared slums and slated for Urban Renewal, disproportionately displacing people of color for interstate highways, civic centers and public housing. Combined with the loss of industrial jobs, white flight, a shrinking tax base, and policies of Planned Shrinkage by local governments, the social fabric of cities was ripped apart, ushering in an era of intentionally designed urban decay and blight.

Epidemics of drugs, violence, disease and fires would follow. Instead of addressing the trauma and systemic crises of the 20th Century, our collective response was to focus on individual behaviors by increasing policing and criminalizing low level offenses leading to the era of mass incarceration—a new iteration of what Dr. Mindy Fullilove in her book, Root Shock, calls serial forced displacement. This mass displacement has helped open to the door to gentrification in formerly Redlined neighborhoods across the country.

Solutions to our most entangled social crises have faltered because we are still living and thinking within the “othering” framework Redlining created. In order to undesign this legacy, we must first understand how our society has devalued whole groups of people through designed systems and social constructs. We must vehemently reject the basic assumptions of Redlining: that some are inherently more valuable and have more to offer society than others. It will require more than patches or policy fixes. We need an intentionally transformational approach.

Just as Redlining was designed, we can see that systems and structures to undo and repair its effects can also be designed. In this new design, those who have been historically shut out will be able to produce and share tremendous value in their communities and, more importantly, generate social and economic value for themselves. Many of the methods for making this transformation happen have been with us all along, and are currently gaining steam.

Erasing social and economic redlines

First, we need to examine what are our underlying intentions and priorities. Are we just trying to fix an immediate problem or can we address something much deeper in our process? This comes through widespread education: understanding collectively how we got into this situation. It also comes through engaging those who have been historically devalued and making sure they have a seat at the decision-making table.

Two years ago, conversations about a forthcoming Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy in one New Jersey city would would lead to two proposals: a center for those who make a precarious living as day laborers, and a center for young and emerging artists with a ‘makerspace’ and freelance entrepreneurial accelerator.

Emphasizing the importance of designing with and not for communities, key questions arose: Don’t young artists and freelancers also look for gigs on a daily basis? And can’t day laborers also be entrepreneurial? Indeed, even the language being used—”Day Laborer” and “Freelancer”—were highly racialized and class based terms, but they were constructs the well-meaning decision-makers had assumed as a given. Could we instead envision that these two classes of workers had more in common than existing frameworks for describing them would lead us to assume?

Breaking from the traditional approach, the group transformed the conversation and proposed a new alternative space. Here, day laborers could offer trainings in the makerspace, and thus be called teachers, allowing those freelancers and craftsmen to work together on shared entrepreneurial projects. With this new perspective place, the two groups could come together to work in ways that would not have otherwise been possible, allowing everyone to contribute and generate something valuable. The result is a newly defined ‘creative class’ that can reinvent how their community works and lives.

A thorough exploration of how we got into current predicaments is also key to designing new ways forward. At the Mary Mitchell Family and Youth Center in the Crotona section of the Bronx, the youth and staff began to engage in a process of understanding and researching their neighborhood’s history—from the development and later demolition of the Third Avenue El, to Redlining, the building of the Cross Bronx Expressway, the destruction of 85 percent of the local housing stock during the 1970s and 80s and the community organizing work to rescue buildings and convert a mostly vacant block into a baseball field.

This research laid the foundation for their collective reimagining of a vacant tenement building the Center owns. Located in the outfield of the nearby converted ballfield, Center staff and young people saw that developing a few units affordable housing in the vacant building would not address systemic issues nor be an appropriate use of resources.

After exploring various models of economic development, the young people identified key elements they wanted to bring to the new space. They wanted a space where neighborhood residents could use their creativity to create value out of nothing (or waste), where elders in the neighborhood could train young people in intergenerational apprenticeship programs, and where participants could launch businesses collaboratively. Most importantly, they wanted the space to be owned collectively in a way that would generate wealth in the community. Importantly, the youth could explain to other stakeholders how each of these key elements addressed their local history of systemic inequality.

Considering housing as an ecosystem

What does the collective design of spaces for shared economic development have to do with fixing the massive housing crisis? For one, it takes us out of the framework that our number one task is to solve a problem. Many past solutions to big problems created even larger crises (think about Slum Clearance and Urban Renewal). Committing to work to address our deep, systemic and entangled history leads to new processes founded on the principle that everyone has value to contribute.

This renewed perspective also takes us out of the narrative that has us believe that tools like affordable housing are an end in and of themselves. Rather we begin to see that goals like sustained livelihoods and a broader ecosystem of home are what many of us seek across lines of race, class, gender and age.

Not only do we need to shift from addressing symptoms to root causes, it is imperative for us to work across existing sector divisions like housing, food, education, health, incarceration, wage equity and the arts. But busting up these “silos” is insufficient if we continue top-down approaches that assume those in power know what’s best for historically redlined communities and the people who stand on the front lines of the collateral consequences of its legacy. If we do not disrupt existing power dynamics, we often merely form a new layer on top of existing structures rooted in the principles of Redlining.

At the core of producing neighborhoods that support the “we” above the “me” is a participatory design process that democratizes decision-making within neighborhoods and that is grounded in the collective knowledge of our shared history.

This means as much as we need to work across, we need to work bottom up. By establishing public gathering places where community data and input are collected, where knowledge is shared and new cooperative projects and housing models are generated, we can begin to undesign the redlines that have divided and devalued us. Thus, opening the door to regenerative economic development that can build shared social and economic wealth.

With this distinct approach we can begin to repair the social fabric and build diverse community relationships critical in today’s highly polarized and divisive climate. Only within this new framework will deep systemic crises like housing inequality be challenged and undesigned.

April de Simone and Braden Crooks are co-founders, Gregory Jost is a partner and Charles Chawalko is lead researcher at Designing the We.

3 thoughts on “Building Justice: How to Undesign the Decades of Racial Redlining that Scar U.S. Cities”

Pingback: Community Developments: Atlanta Preservation Challenge, Housing Inequality – Right Now Help Services

The 1938 HOLC maps are interesting. I looked up the Staten Island map. My current location in New Dorp was a ‘yellow’ (3rd rate) zone back then. I thought that odd since my neighborhood has been a solid middle-class area over the last 100+ years. But I’m guessing that in 1938 my area was an ungraded, undeveloped area without sewers prone to flooding. In Brooklyn parts of Borough Park were also ‘yellow’ zones which makes no sense.

Boro Park was a jewish neighborhood and were on the be cautious list