‘City leaders have asked for our trust to embark on yet another massive jail building spree, at the cost of almost $10 billion dollars. But we can learn from the history of “reform” on Rikers Island, and Blackwell’s Island before it.’

DOC Archives via International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice

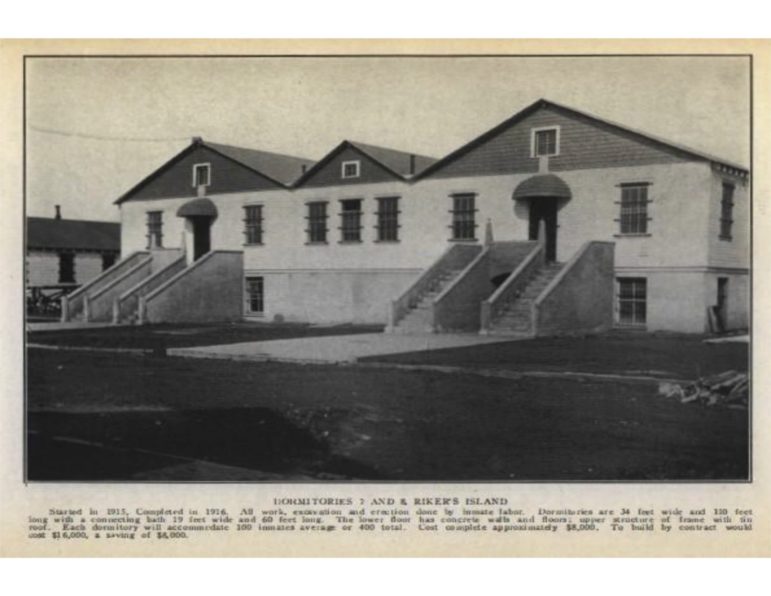

Jail dormitories on Rikers Island in 1916.Segundo Guallpa is one of 12 people that New Yorkers have lost to the deadly custody of the Department of Corrections this year alone. Mr. Guallpa’s story reveals the dark heart of our city’s correctional history: we have tried over and again to use caging to solve our problems. To a city whose leaders have offered only a hammer, every problem is a nail. But if one hundred years of crisis and “reform” at Rikers Island shows us nothing else, it is that incarceration will not, and cannot, save us. It is time we try something new: invest, not in new jails, but in our city’s families and communities—and in the restorative programs that address the underlying causes of violence.

Luz Gualman, Mr. Guallpa’s wife of 37 years, decided to involve the criminal legal system in her marriage, after years of escalating harm, because she wanted to “give the criminal justice system a chance” at solving her family’s problems. Her husband’s substance use disorder had created an unsafe home, marked by violent abuse. Ms. Gualman believes that Mr. Guallpa’s substance use was triggered by a series of traumatic incidents, she told reporters, including an almost-deadly assault and robbery in 2013, after which his drinking reached new, terrifying heights. Ms. Gualman wanted help for her husband, but instead of treatment for both his alcoholism and the underlying trauma with which he was using alcohol to cope, Mr. Guallpa was sent to a cage. He committed suicide at Rikers Island less than two weeks after his arrest.

What those in power will have you believe is that the violence and death that stalk Rikers will be solved by the next jail, that “modern and humane” one just over the next horizon. They have told us that this new jail system will provide “space for quality education, health, and therapeutic programming.” But the history of Rikers itself shows us that this reform isn’t possible; that jails cannot address the underlying social problems that we have asked them to solve.

Before Mr. Guallpa ever set foot on Rikers Island, 136 years earlier, a “happy idea suggested itself” to the New York City Commissioners of Charities and Correction: purchasing Rikers Island on which to build “an enormous model penitentiary, ample in size to serve for many years to come and which in all its plans and parts should be the most perfect prison in the world.” The Commissioners were seeking to solve the “emergency” of violence and overcrowding at Rikers Island’s predecessor on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island). Rikers Island was to be the solution: a humane, progressive jail created in consultation with the “best European authorities.”

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

As Jarrod Shanahan and Jack Norton detail in A Jail to End All Jails, “from its inception, Rikers was a place of abuse and corruption.” But in 1954, spurred by the spirit of the early 20th Century’s Progressive Era, a reformist judge by the name of Anna Moscowitz Kross took over control of the Department of Corrections. Kross believed that the city’s incarceration system “was not correcting, though we are a Department of Correction.” In order to realize her vision to make treatment and rehabilitation the primary objective of the DOC, Kross brought in social workers, clinicians, and educators to augment the cadre of traditional correctional officers. At that time, the city’s incarcerated population was scattered across various borough-based facilities, which were also notorious for squalid conditions and violent abuse. Kross sought to consolidate all of the city’s correctional facilities onto Rikers Island. She believed that the rehabilitative model could only be realized by closing the borough-based jails and building new gender- and youth-specific facilities on Rikers.

Yet Anna Kross did not leave behind a legacy of “humane conditions” at Rikers Island; the new jail complex on Rikers was plagued by just as much violence and misery as the decades before and after her tenure. Instead, Kross’s legacy can be found in the massive expansion of the city’s incarceration capacity on Rikers Island, realizing her liberal reformist vision to use the island, that “model penitentiary,” as the principal response to the city’s social ills. As such, the incarcerated population rose to new heights, increasing from 6,667 in 1954 to 9,000 in 1960. That rise would continue unabated for decades, until Rikers became the largest jail complex in the country, at a peak of over 20,000 in 1991. It was in the Anna M. Kross Center, the largest facility on Rikers Island, that several people died in 2021. The building is a monument to the failure of progressive Rikers reform.

Commissioner Kross’s reforms should sound familiar. They are part and parcel of the carceral humanism that undergirds the plan to build “modern and humane” borough-based jails to replace Rikers Island. The very same arguments that Kross used to convince city leaders to finance her Rikers reform project have been dispatched yet again. Instead, now the reformers claim that the problems on Rikers can only be solved by the borough-based system that we left behind 60 years ago. The city’s jail plan resounds with the echoes of reformers past, claiming that these new jails will be completely different, “designed to foster safety and well-being,” with a “network of support systems” that have treatment and rehabilitation at their center. Just as Anna Kross promised before. But would new jails have solved the problems that plagued Segundo Guallpa, Luz Gualman, and their families?

City leaders have asked for our trust to embark on yet another massive jail building spree, at the cost of almost $10 billion dollars. But we can learn from the history of “reform” on Rikers Island, and Blackwell’s Island before it. We can learn from the massive new jail complexes built in cities like New Orleans that are still racked with death and despair. As Mariame Kaba warned at a Council hearing in 2019: “We will be back in this room, I promise you, in 10 years, if these four new facilities are built, calling these facilities inhumane.”

Incarceration is the problem, not the solution. We must demand something new: the kind of investment in our communities that can address the underlying problems, those that we have long sought to hide on an island of trash.

Nicholas Barber is a New York-based writer and advocate who most recently worked at the Southern Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit law office that challenges legacies of violent racism in the criminal legal systems of Georgia and Alabama.