‘It is unacceptable for NYC schools to continue to expect students to succeed knowing that access to reliable internet connection and devices still remains spotty at best.’

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

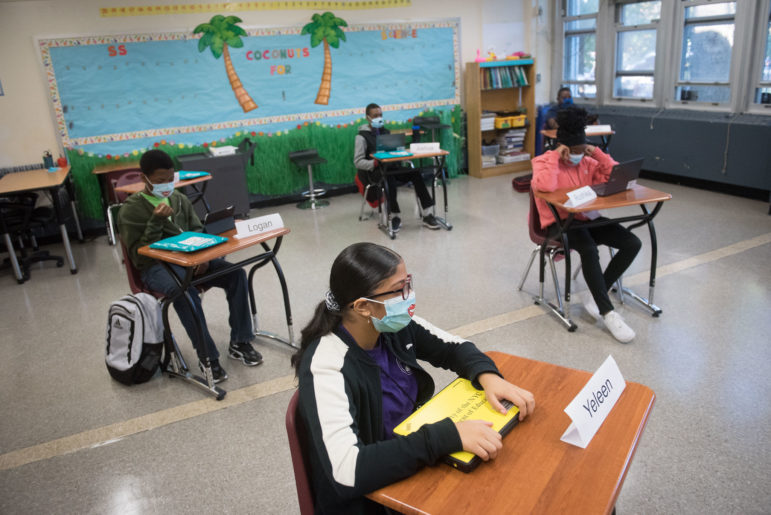

Students work on laptops in a NYC school during 2020.The start of this school year marks the third in a row where students will be attending classes in settings radically shaped by the pandemic. And continued uncertainty with the Delta virus means remote or hybrid learning contingency plans are still front of mind for parents and educators.

But for millions of students, truly effective remote learning remains out of reach. A recent analysis of statewide data representing more than 2.6 million students by the New York Civil Liberties Union found in New York City, 14 percent of students didn’t have devices and 13 percent lacked internet. By the city’s own estimate, more than 1.5 million New Yorkers have neither a mobile or home broadband connection.

In the year 2021, these figures are unacceptable. And it is unacceptable for NYC schools to continue to expect students to succeed knowing that access to reliable internet connection and devices still remains spotty at best. All New Yorkers are able to recognize the value of connectivity—both digital and otherwise. Connections to people, education, opportunities—and particularly in today’s world, the internet—are critical ingredients of a successful and fulfilling life.

I know this first hand. Growing up in Queens in a small apartment with a single mom, it was connections made that granted me access to special programs in NYC public schools, allowing me to eventually become the first person in my family to go to college. As long as New York City students’ connectivity to teachers and classes remains at risk, an entire generation of young learners will be left behind.

The internet is a requirement for many facets of daily life: to sign up for a vaccine, register to vote, complete the Census, file taxes, apply for jobs, consult with a doctor, or train for a new career. If we treated internet connectivity like any other utility—water, gas, electricity—these shortfalls in delivering an essential public good would be an outrage. Indeed, the news last fall was filled with accounts of frustrated parents and teachers whose students were missing out on their first day of school for lack of devices, or had to patch into class on a borrowed cellphone with a cracked screen. Although the city hustled to get hundreds of iPads and wifi hotspots out in the mail, the wait for learning devices took as long as six weeks in some parts of the city, and some requests may have gone unfulfilled.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

This scrambling is all the more wrenching for the disparate harm it has already inflicted on young students of color. At the end of last school year, students in majority Black or brown school districts were four times more likely to have inadequate or no internet, and three times more likely to not have a dedicated device to use for school, according to the NYCLU report. Learning loss during the pandemic has also disproportionately impacted these students.

Despite the plan to return to fully in-person learning in New York City this year, we all know how quickly this pandemic can upend our plans. We can no longer deny that technology and internet connectivity is absolutely crucial to students this year, and every year.

The mayor’s recent dedication of $112 million in federal stimulus funds to help address the digital divide is welcome news. More learning devices are being distributed, on top of the hundreds of thousands already issued last year. I’m proud that grantees of Siegel Family Endowment have helped students maintain access during the pandemic: For example, NYC FIRST, which provides STEM education to New York City students, sent out hundreds of “Robot in a Box” kits to continue hands-on tech learning at home. But relying on this ad hoc approach is no longer an adequate response.

For thousands of students, the damage has already been done. Too many questions remain about which students are getting the resources they need and who is being left out. A recent comptroller audit found that the Department of Education lacks formal procedures for tracking and reviewing data on these disseminated devices.

Despite the city’s challenges with virtual learning over the past eighteen months, I still believe that reimagining and creating new ways for people to learn and develop skills online is a robust frontier of educational technology. Online learning is more than a pandemic-era backstop; it is the future. City Hall and the Department of Education need to conduct an honest assessment of the current state of students’ ability to access online learning.

Our new mayor should develop a cross-agency task force to address issues in education access caused by systemic barriers—from lack of broadband and devices, to missing childcare services, to housing stability. Across the public, private, nonprofit, philanthropic, and community-based sectors, we must work together to build a digital infrastructure that is comprehensive, equitable, and inclusive.

Katy Knight is the executive director and president of Siegel Family Endowment.