David Brand

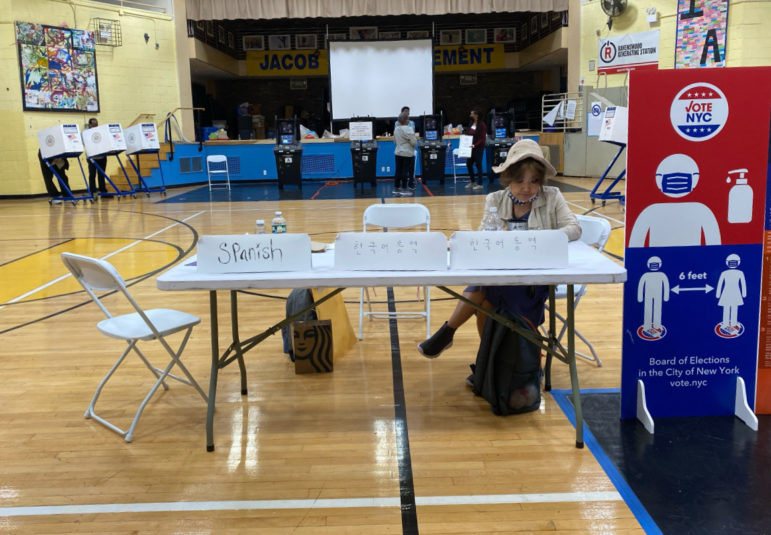

The polling place at Queensbridge Houses, where Spanish and Chinese-language translators had yet to show up on the morning of primary day.At the Jacob Riis Settlement Houses poll site in the Queensbridge Houses, a table was set up Tuesday morning to offer translation services for voters. But some chairs sat empty: two of the three Board of Elections translators slated to serve the site—its Spanish-language and Chinese-language interpreters—had yet to show.

Poll site coordinator Margaret Johnson said they notified the city’s Board of Elections of the snafu. “They told us there’s nothing they can do. They don’t have any more,” Johnson said. “We’re trying the best we can.”

Poll workers were giving out information cards in seven languages to try to fill the gaps. The lone interpreter at the site Tuesday morning, who was providing translation services in Korean, was using Google Translate in an attempt to assist voters, who are being asked to vote differently this year under the city’s new ranked choice voting system.

“They need to fix this,” Queensbridge Houses Tenants Association President April Simpson told City Limits. “We’re the largest housing development in the United States.”

The BOE did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Campaign workers for candidates running in City Council District 26, where the Queensbridge Houses is located, told City Limits that DemocracyNYC—a city program charged with increasing voter engagement—was sending interpreters to the site the fill the gap, though the initiative did not immediately respond to a request for comment to confirm this.

The BOE is required by the Voting Rights Act to provide language assistance at select city poll sites in specific languages: Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Bengali, Punjabi or Hindi. In addition to those services, the New York City Civic Engagement Commission (NYCCEC)—established as part of 2018 changes to the city charter that aimed to increase voting access—offers its own interpreter services at some 55 poll sites across the city in other languages: Arabic, Bengali, Chinese (Cantonese, Mandarin), French, Haitian Creole, Italian, Korean, Polish, Russian, Urdu and Yiddish. A map of those locations can be found here.

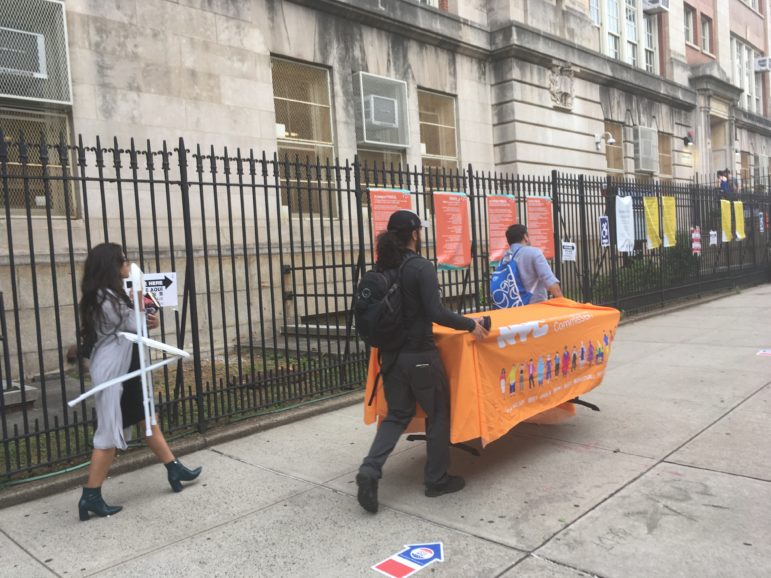

Among them is P.S. 85 in Astoria, where the NYCCEC was offering assistance to voters in Italian on Tuesday, in addition to services being provided there by the BOE in Spanish and Bengali. There was some initial confusion over where the Italian NYCCEC translators were allowed to operate: When polls initially opened at 6 a.m., they had set up shop outside 100 feet away from the voting site, next to candidate campaign volunteers.

After City Limits asked why they were outside, one of the coordinators called the BOE to clarify the rules. Around 8:25 a.m., the NYCCEC interpreters were allowed into the building and set up shop in the school’s hallway. The staffers declined to comment on the switch.

Other city poll sites were also experiencing hiccups and some worker shortages Tuesday. At Frank Sinatra High School on Astoria’s 35th Avenue, a worker told City Limits that a little less than half of the 42 poll staffers had failed to show up to the site in the morning.

“It’s difficult when you want to take a break,” one poll site coordinator said of the situation. The BOE was notified of the shortage by 7 a.m., the coordinator said, and they told her help was on the way, but no one had arrived by 10:35 a.m.

Over in Manhattan, it had started to rain by the afternoon, causing issues at the polling site inside the Church of the Heavenly Rest, a gothic Episcopal church across from the Engineer’s Gate on 5th Avenue. Carmen Mathis, the site coordinator there, has bad memories of the last time an election day saw bad weather — in 2018, three of her scanners jammed, making them unusable for over two hours. This year, she said, the dampness on people’s hands from the humid air was similarly causing some machines to jam.

“But it’s nowhere near as bad as 2018,” she said, adding that early voting has helped to mitigate the crowds on election day. Indeed, the crowd was thin in the mid-afternoon, with several voters sitting in the pews, filling out their ballots with towering stained glass windows behind them. “It’s very serene and calming in this site,” said Mathis.

The vibe was less serene just a few blocks away at Robert F. Kennedy High School (P.S. M169). The voting site, held in a humid basement gymnasium, was busy at around 5:30 p.m., with a steady stream of damp voters at the check-in station and the scanners. “Terrible,” said coordinator Vincent Milo when asked how the day has been. He said he is short 20 poll workers, then scurried away to fix a jammed scanner.

At Yorkville Community School on 88th Street and 1st Avenue, a handful of early risers were already at the polls shortly after they opened at 6 a.m. Coordinator Brenda Richards weaved through the stations set on a bright chartreuse floor, counting volunteers and talking into her cell phone with a medical mask slung across her chin. “We have only one person at each table, and a table with nobody,” she said. “Send 10 people.”

At 6:20 a.m, a volunteer flagged her down. “We have a ballot jam,” the volunteer told her. “Already?” Richards responded, reaching again for her cell. “Come on, y’all!”

By 8 a.m., the site was bustling with a steady stream of voters but without a wait time. Richards reported that the broken scanner had been fixed and everything was functioning smoothly. The requested 10 poll workers, though, had still not arrived.

“The main thing I need is the people,” she said.

–Daniel Parra, David Brand, Liz Donovan and Jeanmarie Evelly

2 thoughts on “Worker Shortages at Some NYC Polls: Missing Translators, ‘A Table With Nobody’”

One solution to this issue could be to increase funding and resources for the New York City Board of Elections to hire and train more poll workers and translators. Additionally, increasing public awareness of the need for poll workers and translators and encouraging individuals to volunteer at their local polling stations can also help alleviate this issue.

Nu uitati sa vizitati Terasa Cu Carti to watch lista seriale turcesti subtitrat in Romana.