Murphy

The sound permit for the Saturday rally in Harlem protesting the death of George Floyd and other slayings of Black people came late, according to the man who organized it, Craig Schley. So, as several dozen police officers stood in the shadows of the state office building on 125th Street, Schley used a megaphone to address the crowd gathering around the statue of Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., suggesting the armed force observing him didn’t matter. “I’m seeing red, not blue. I’m seeing red,” Schley said, to cheers of agreement.

“Destiny lies in your hands. And whoever is in office today is not your future,” Schley said. There was a voter registration table set up. Schley has run for Congress twice and this year mounted a challenge to incumbent Assemblywoman Inez Dickens. He did not make the ballot.

It was not clear that the crowd, in general, had much faith in electoral solutions.

The mics came soon thereafter, but by the second speaker, a stream of people began peeling off and moving down Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard. “Fuck the speeches,” said one man, as he turned away from the stage amid a chorus of horns honking in support.

Hundreds filled the west side of the boulevard. They chanted “Whose streets? Our streets,” “George Floyd” and “Fuck the Police.” As was the case at the Powell statue, almost everyone wore masks, but it was impossible to maintain six feet of distance. Cars driving north honked. People leaned out their windows to shout support.

At 116th Street, the group stopped, circled and knelt. A single NYPD van pulled up and dropped off a handful of officers. The march resumed its path south. A dozen or so NYPD motorcycle came along the northbound side of the boulevard. At 111th the group swung left. “NYPD, suck my dick” was the chant now.

A small group of young men keep tight control on the front of the march, slowing here, speeding there. Deputies on bikes raced ahead to seal off intersection and bid cars to turn away from the march. A young guy on a motorized scooter kept racing off to gather intelligence on the movements of police and then report back.

As the crowd surged east, filling the block, one of the lead organizers beckoned his fellow marchers to stay close together. “We’re going to take the highway,” he said. They ran a block, apparently to gain a little lead time over the police who were probably moving along parallel streets. No one menaced bystanders. Nothing was turned over, smashed, or pounded it on. The crowd was peaceful and swift.

At 1st Avenue, cops on bikes and motorcycles formed an L-shaped barricade to force the crowd south. The protesters locked arms and moved Whites to the front, expecting a clash. As they encountered the blue barrier, a few stopped to hurl insults or chant at the officers. But the leaders moved south, then turned onto 110th. They had an objective.

Two cops trailed the head of the pack, but there was nothing stopping the group from vaulting onto the FDR Drive. As dozens spilled onto the roadway, halting traffic in both directions, no more than five NYPD officers stood about 100 yards south.

The crowd began moving down the highway. They chanted “I can’t breathe” and “say their names.” A group of officers on bikes tried to form a barrier but the crowd flowed around them. There was a skirmish or two. Instead of a line, the bike officers formed a self-protective circle. The crowd pressed on.

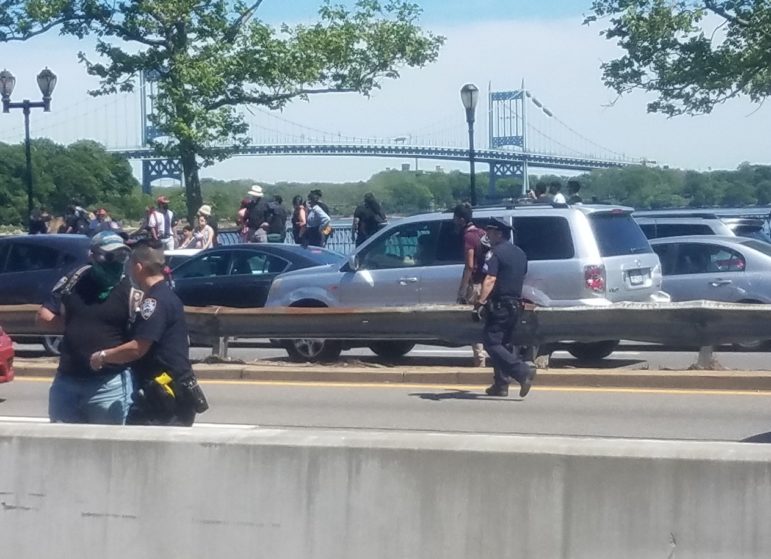

A team of motorcycle officers started to take position a few blocks south, then moved further back, to just beyond the 96th Street Exit ramp. Unable to pass along the southbound side of the highway, the front of the crowd jumped the median to move along the northbound lane, but by then, a few other NYPD vehicles had arrived and officers raced across the guardrail, making the first arrests. Some protesters made it to the walking path along the river. Six or seven got arrested.

As the arrested were led toward NYPD vehicles, an officer from the department’s legal bureau leaned toward a commander with what sounded like a gentle reprimand. “The summonses have to be personally observed,” he said. “I just saw three guys, and [the officers holding them] were like, ‘I don’t know what they did.’”

Now the march’s southward movement had been stopped. A small group of officers, including a couple white-shirted commanders, began walking up toward the main group of protest that was lingering a few dozen yards north. Someone threw a bottle that smashed near the NYPD personnel. “OK, let’s go,” one of them yelled, and the officers charged. They grabbed five or six more people, including a man and woman whom they wrestled to the ground. The rest of the crowd gathered around the scene, demanding the people be released. “He was moving back.” “Let … her … go.”

“Everyone come up!” one commander, apparently worried about being too badly outnumbered again, yelled to officers who were standing well back from the action. A diminutive cop stood on the opposite side of the jersey barrier until a boss barked at her, “Get over the fuckin’ wall.”

The arrestees were led away. A wall of officers came down the FDR. The protesters began to retreat toward the sidewalk. “We’re regrouping at 96th and 1st,” someone shouted. A line of helmeted officers (“Oh, those are the riot cops,” one protester remarked) blocked the street. Nodding toward the cops, who had gone from badly outnumbered to everywhere, another marcher said, “They’re like water.”

The crowd drifted south and west. They gathered in a mass near a gas station on 96th. An NYPD van pulled up. The officers stepped out, stood on the sidewalk for a few minutes, and went away. A bespectacled young man was standing on something, addressing the crowd. The march was going to continue on the sidewalk, peacefully, he said. They’d keep moving around whatever obstacles they encountered. “You’ve got to be like water,” he said.

Murphy

Craig Schley addresses the rally at the State Office Building.

Murphy

A march breaks off down Adam Clayton Powell.

Murphy

Kneeling in quiet protest at 116th Street.

Murphy

Police force the march south at 1st Avenue.

Murphy

A lone cop observes as marches approach the barricade to the FDR Drive.

Murphy

Over the barricade.

Murphy

Traffic stops.