The Guardianship Project, Vera Institute of Justice.

Kimberly George, Director of the Guardianship Project, Vera Institute of Justice, at her home. Since March 13th George has picked up and scanned nearly 600 pieces of mail containing clients’ bills, benefits paperwork, income checks and health insurance.On March 27, John, a 68-year-old, succumbed to COVID-19 one day after he was diagnosed with the disease. He was one of 167 people that passed away in the city that Friday. Already afflicted with COPD, peripheral vascular disease and diabetes John (not his real name) had little chance of surviving. In fact, his health had been so fragile for so long he’d spent a dozen years in the state’s guardianship program—a program now facing immense challenges protecting its extremely vulnerable charges from the ravages of the pandemic.

In 2008, after 20 years of homelessness, a hospital petitioned for John to be enrolled in the state’s guardianship program, and he spent the last 12 years of his life under the watch of The Guardianship Project, an initiative of the Vera Institute. The guardianship program was implemented for individuals like John who are unable to make their own health or financial decisions. They are often those determined by a judge to be “incapacitated” due to a wide variety of issues, including dementia, serious medical problems, pending evictions, elder abuse, and placement in institutional settings against their will. If family or friends are unavailable to take responsibility, the court will appoint a legal guardian. While anyone over 18 qualifies for the program, most participants tend to be the elderly.

Data on how many guardianship cases in the system are fuzzy but from 2007-2011 there was an average of 2,400 cases per year, according to court data.

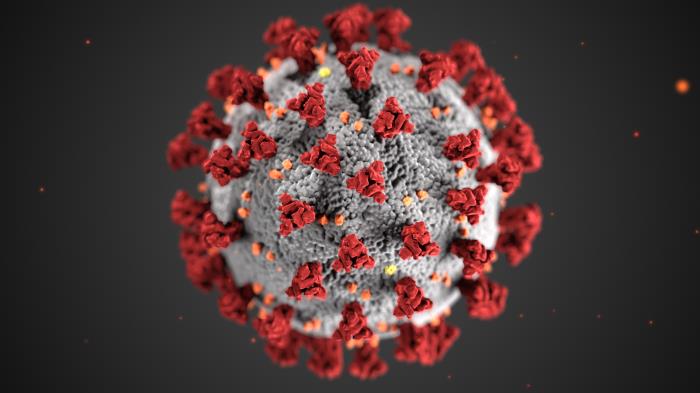

From disrupting grocery delivery services to shaping how medical decisions are made, COVID-19 has disrupted the arrangements that have helped the vulnerable New Yorkers enrolled in guardianship programs achieve a semblance of a normal life.

In most cases, staff in these organizations have to take on multiple roles to meet the needs of this vulnerable population. About 40 percent of the 174 clients in the guardianship program run by the Vera Institute live independently at home. Some rely solely on social workers for groceries, medication, or money. Without gloves or masks, social workers have to make grocery runs because grocery delivery services are hard to obtain. “We’ve had to find alternative methods for getting groceries to 25 clients,” says Kimberley George, director of the guardianship program. “Our social workers are going to grocery stores, doing the shopping, and delivering the groceries to clients in their homes,” she added.

As of Monday, 11 Vera clients have died since the pandemic began. At least six were confirmed to have COVID, and it is suspected in the other cases. Fifteen other clients are sick.

Marco Damiani, CEO of AHRC NYC, an organization that supports thousands of intellectually and developmentally disabled people, says staff now have to act as counselors to those clients who have lost friends. The organization has already lost 12 clients and four staff members to COVID-19. “Our staff are also now … being mental health counselors,” he says to City Limits. “People no longer have their roommates or their friends and it’s harder for them to understand it,” he added. Damiani says his organization has launched a virtual mental-health platform where psychologists and social workers can now talk to staff and residents.

Because most clients in the guardianship program are elderly and already suffer from poor health, simple decisions such as whether to send someone to the hospital —where they risk exposure to the virus— are now complicated. “While in normal times sending a client to the hospital is a safety measure, with the pandemic, we are trying to avoid sending clients to the hospital if at all possible,” George writes in a follow-up email.

George says another challenge guardianship programs face is convincing some clients who live independently—and may not understand the gravity of the situation—to stay home. “We have some clients who want to go out either because they don’t understand what’s going on right now or they don’t understand that they need to stay put.”

Damiani echoes a similar sentiment. He says the pandemic is affecting some residents who may not fully understand the disruption in their daily routines. For example, some programs have been temporarily shut down and face-to-face services have been limited. Movement in and out of the group homes is also restricted.“This is very upsetting to folks with autism. It’s very hard for them to communicate their fear. So, they act out of fear. They may strike out at somebody. They may become very isolated and not cooperate,” he says.

But for Damiani and his organization, another threat looms large on the horizon: anxiety about a possible delay in state funding. In a little over a week, funding for organizations such as AHRC NYC will run out. Damiani says they have been unable to get assurances from the state about whether funding will continue at pre-COVID-19 levels. Despite many programs shutting down, Damiani says he is concerned that any cuts will make it harder for organizations to retain their workforce. “We do have increased call out rates. I think with every organization the workforce is less robust than it was,” he says. “In a week or two if we don’t have additional resources, we may have a staffing challenge,” he added.

In a statement to City Limits, the Office for People With Developmental Disabilities, the state agency responsible for the funding says it is working with the federal agencies “to sustain providers by providing retainer payments to provider agencies in recognition of the costs incurred as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.” The agency says it “will continue to work with providers of services through this difficult time to ensure they receive the needed resources to continue to provide quality services,” the statement continued.

While guardianship programs face many challenges, George says she worries more about those elderly New Yorkers that are unknown to the system. “What we are most concerned about is people who do not have family, friends or guardians. We are worried that those people would fall through the cracks,” she says.

Ruth Finkelstein, executive director of the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging at Hunter College, agrees. She says people who have guardians or are in congregate settings are in better shape than those not known to the system. “People who are frail and may lack capacity in all kinds of ways are even more worrisome because they are not necessarily known to any system of care,” Finkelstein says. “It’s very concerning to think about people who are behind those doors and what do they need,” she added.

According to George, the actual number of cases among clients is unknown since some nursing homes have stopped testing. Some of those tested positive suffer from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or dementia. “We are also being told by the nursing homes that they are understaffed and lack the appropriate protective equipment,” George says. “One of our ill clients is completely bed-bound and in their own room, leading us to believe they must have caught the illness from a staff member.”

As case counts begin to subside, the focus will shift to what could have been done better to protect all New Yorkers, especially the most vulnerable, from the coronavirus.

“We’ve learned a lot of lessons on what we need to do to be prepared,” George says. “We have to ensure that our safety net is robust enough that every person in society has somebody looking after them whether it’s family or friends, community-based organization,” she added.

Unlike many unforeseen service disruptions, John’s funeral went relatively smoothly. Thanks to a prepaid funeral contract signed in 2010, it was one set of decisions that didn’t have to be made under the pressure of a pandemic.

2 thoughts on “Guardianship Programs See Rising COVID-19 Death Toll”

Guardianship is totalitarian dictatorship. Two of your famous guardians are April Parks and Rebecca Fierle. The Catholic church also kills seniors “with dignity,” whatever that means. Join the Facebook group “Stop Terrorist Guardians”

Here is a more complete list of Facebook groups about abusive guardianships http://larrytessari.com/personal/fbgroups.htm