Murphy

Making sure students have laptops is important. But teachers and parents say access to WiFi, guides for how to navigate online learning, a clearer set of goals and new emotional support are also needed.For New York City teachers, students, and parents, the first week of remote learning came with frustration, anxiety, technical difficulties, and questions about what the future holds for the country’s largest school system.

When Mayor de Blasio and Chancellor Carranza moved to close schools, access to laptops, iPads, Chromebooks, and other devices for students across New York City was one of the biggest questions for parents and teachers.

While Carranza and de Blasio promised to distribute devices to the 300,000 students without personal computers or Internet access, thousands missed out on learning in week one. Even for students who have access to their teachers and assignments, adapting to remote learning has been difficult.

Based on interviews with teachers, providers and others, here is a snapshot of how week one went:

Machines not delivered

The scarcity of devices was anticipated as one of the largest challenges to remote learning. Organizations like Win NYC and Bronxworks, which run some of the city’s 450 shelters for families and single adults, have firsthand knowledge of the large number of students who do not have devices.

According to a Win spokesperson, their organization needed 1,400 devices for students and as of Thursday evening had only received around 375 for one shelter in East New York.

“The mayor’s announcement that they would deliver 300,000 devices to our students excited parents from our shelters, who were afraid their children would be left behind, and now those children have been totally forgotten,” says Christine Quinn, CEO/President of Win NYC. “I feel, I believe, and I know laptops should have gotten to these kids sooner, because now our kids have lost a week of remote learning.”

While Win has received one delivery, Bronxworks was still waiting for the 159 tablets and iPads they’ve requested from the DOE. Resident Director Estrella Montanez expects a delivery by Monday and seems more upbeat that the DOE will make good on their promise.

However, Montanez’s biggest worry is her facility not having Wi-Fi access.

“The DOE said they would provide us with tablets and iPads that are Internet enabled with data plans, but we do not have Wi-Fi in our building, so our students either have to congregate together, or leave the building to gain access to hotspots,” says Montanez.

The gaps don’t just affect students who live in shelters. According to Dr. Carmen Applewhite, who teaches fourth and fifth graders in Brooklyn’s district 13, says some of those who live in homes there are also struggling to gain access to the platforms needed for remote learning.

“Most of my students are able to get on Google Classroom, but some teachers and parents have students waiting for devices, and waiting for their requests to be answered while their kids are falling behind in their assignments,” says Applewhite, who still has three of her own students waiting for devices that were requested last week.

A lack of prep time

The question of whether schools were closing or not came at every press conference the week leading up to the decision on Sunday, March 15, when the city finally chose to shut the doors of all New York City Public schools. For several teachers, the last minute decision was a disservice to students, because if they are not prepared then students will not get a full scope of their lessons.

“We needed more time to prepare, and we didn’t get it. The announcement to close happened on Sunday, and never once was it discussed with us in a real way of how we were going to move forward together,” says a social worker at an E. Harlem public school. “I have parents who don’t know how to access their children’s online classes, and students who have trouble doing the work, because of distractions at home or not having access to the Internet, and it’s become increasingly difficult for me to step in and help when we are still trying to navigate through this.”

“We didn’t even have a full week to prepare for this. We only got three full days to actually prepare for remote training,” says. Applewhite, who also claims that the DOE did not formally reach out to teachers until tuesday to inform them how they would go forward with the remainder of the school year, or at least until they could safely return to school. “These students deserved a better response, and so do the teachers, and we all deserve transparency from the DOE going forward.”

A parent’s worry

For Milly Tejeda, 31, of the South Bronx, remote learning presents a variety of issues. For starters, her 6-year-old son Evan is an Individualized Education Program student, and requires speech therapy services. Her biggest fear is the effect this sudden disruption in her son’s learning process will have going into the next school year.

“I know Evan can do the work. He is intelligent, but I fear that without his services he will regress, because the way he has to learn and the techniques they use at school is something I am not fully equipped for at home,” says Tejeda.

She hopes that starting next week Evan will have some sense of a normalcy, but for now there seems to be nothing but uncertainty. Including the amount of time she can dedicate to helping him.

“I am frustrated, because I want to give him more time than I really have, but I also have to work and even though I am home, I’m just not able to help him with his school work until my work day is done,” continues Tejeda, who is an administrative worker at NYU Langone. “To make it worse I don’t think there was a clear line of instructions for parents, and i wonder why we weren’t given better directives to get our kids ready for remote learning.”

Along with the lack of direction Tejeda has been unable to access Evan’s assignments.

“Since Thursday I haven’t been able to get his assignments online. Luckily I have been in touch with his teacher, who reached out to IT and we are hoping that we will be back on track by monday,” Tejeda says, anxiously.

A whole new game for teachers

The day-to-day process of remote learning is also a concern for the city’s teachers. Their workload has increased and their methods of teaching have had to change. For ninth grade teacher Beatriz Reynoso, week one has come with frustration–professionally and emotionally.

“Honestly, It’s overwhelming for us all, because it’s much easier being able to explain things and go over work in person for both students and teachers, but right now we have to make due with what we have,” says Reynoso. “We also have students who we know for sure have access who haven’t responded to emails or logged in to office hours, but are doing assignments, and some who haven’t done anything, but this is all hard to gauge, because unless we communicate with them, we won’t know what they are actually able to learn.”

Reynoso’s school is following an asynchronous model, so they currently have no live classes. They post work with due dates and each teacher has office hours throughout the week for students to check in via Zoom.

Reynoso and several other faculty members at her school have had students reporting difficulty getting online to do assignments.

But the challenges of remote teaching are more than technical.

“It’s been emotionally difficult for me and my students. One of our students was on the verge of tears during our class session yesterday, because they miss their friends, they miss coming to school, and I just think there is some fear with all this change,” Reynoso tells City Limits. “Even my anxiety is on overdrive. I’m barely sleeping through the night, I have bouts of crying and I just have a lot on my mind.

According to Reynoso, a lot of students have reported feeling depressed and unmotivated, but she remains positive and does her best to stay in touch to show them they are not alone right now.

How will the school year end?

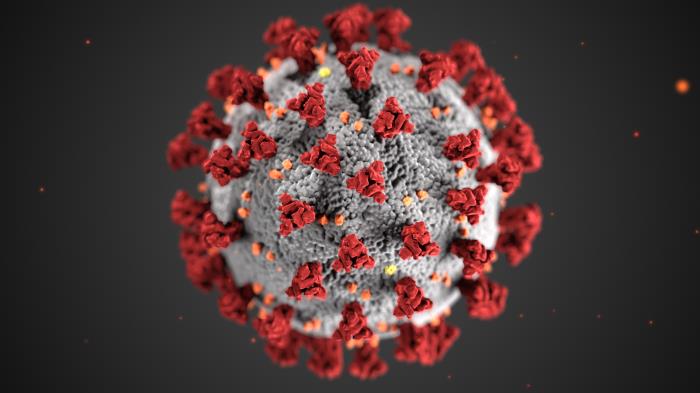

Though it’s been only one week, the biggest question is how will students be graded at the end of the year. De Blasio wants to reopen school on April 20th, but the likelihood of that is rapidly dwindling as COVID-19 cases continue to increase.

The thought is that if the DOE is unable to work out the kinks of remote learning, then the students should not be penalized.

“Right now the DOE needs to communicate better with all of us; parents, teachers and students need to know,” says Applewhite. “The DOE needs to explain to everyone that students cannot be penalized because they are losing a portion of the year, especially when there isn’t a universal platform and equal playing field for them.”

For parents, it remains unclear how potentially losing the rest of the school year could impact their children’s ability to pass into the next grade.

“I have my concerns about Evan advancing to the next grade, but I do not believe he or any other student should be penalized for what’s happening right now, especially if students are having trouble accessing their work online,” says Tejeda. “It has not been part of any discussion, but I am curious how students will be graded throughout all this if the issues don’t get handled.”

The DOE was contacted for this story, but a response was not received by press time.