Adi Talwar

The New York City Panel on Climate Change has predicted that under a worst-case scenario where the Antarctic ice sheet melts more quickly, the city could face nine feet of sea level rise by the end of the century — a water level that would permanently submerge entire neighborhoods, including all of Coney Island.

The water first rose up out of the streets in Coney Island, recalls Ida Sanoff, sometime last summer.

“I was standing last summer on the corner of Mermaid Avenue and I think West 19th Street, and it hadn’t rained in several days, and the entire intersection was a lake,” she recalls. “And all of a sudden as I watched, the water started going down.” The next day at the same time, the same thing happened. “Sure enough, I pulled out my phone — the tide was going out.”

The phenomenon is known as “blue-sky flooding,” and occurs when rising tides reach the level of sewer outflows, sending seawater (and sewer water) backing up through storm drains. It’s become increasingly common along the Florida shore and other coastal cities, but until now hadn’t been a part of Coney Island life.

Meanwhile, a little less then a mile west down the peninsula, developer John Catsimatidis’ soon-to-open 21-story luxury rental project Ocean Dreams towers over the neighboring public housing blocks. And Sanoff’s puddled intersection itself is in the process of being torn up — ironically — for a sewer project to prepare the way for a massive 1,000-unit residential complex that is about to rise across the street from the Brooklyn Cyclones’ ballpark.

That juxtaposition — of a city with more residents at risk from sea level rise than any other in the U.S., yet still building new waterfront construction at a breakneck pace — has some New Yorkers wondering if two of the de Blasio administration’s signature issues, housing construction and green planning, are on a collision course along the city’s 520 miles of shoreline. The mayor’s office says it can do both, pointing to billions of dollars being spent to mitigate the impact of rising sea levels.

But as climate experts warn with increasing stridency, coastal cities are running out of time to prepare for threats from the ocean — and seawater is an implacable adversary.

“I have to give the city props” for swiftly shoring up its existing infrastructure, says City Tech architecture professor Illya Azaroff, an expert in climate-change preparations, which should “buy us 10 or 15 or 20 years.” But coming up on seven years after Sandy, he says, “we really need to learn to work with water — we need major surgery, versus just Band-Aids.”

“Even the Dutch are retreating from the shoreline, but here we’re building out 30- and 40-story buildings in a flood zone,” marvels Sanoff. “It’s all about money. And the developers don’t give a damn because they’re not going to be here.”

The reality of climate change and its inevitable impact on New York City came crashing down in October 2012, when Hurricane Sandy made landfall, bringing with it a 13-foot wall of water that flooded subway tunnels and neighborhoods, cut off power to lower Manhattan, washed away century-old structures, and left the city forever changed.

Sandy “was a turning point in our climate resiliency work,” says Jainey Bavishi, a former White House climate official who since 2017 has served as director of de Blasio’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency. That’s true not just for anticipating future Sandy-like storms, but also for predicting overall sea-level rise and such climate-change impacts as more frequent heat waves, which the New York City Panel on Climate Change projects will triple by the 2050s. (By the 2080s, the panel predicts, New York City could experience 75 days per year where the temperature breaks 90 degrees.)

All indications, in fact, are that while Sandy may have been unprecedented at the time, within a few decades it will likely be the new normal. Sea levels in the city are now about a foot higher than they were at the start of the 20th century, thanks to global warming. That relatively modest rise will soon be dwarfed by the effects of swiftly rising atmospheric carbon: By the end of this century, according to climate scientists’ best estimates, sea level in New York will rise another four to six feet. (Things will look somewhat better if humans massively reduce carbon emissions starting in the next few years, but not all that much; the warming effect of atmospheric carbon takes time to build up, so much of future sea level rise is already baked in from past greenhouse gas emissions.)

That’s bad enough for everyday tides, which will be increasingly surging into waterfront homes. It will be far worse when it comes to storms: With sea level already at a higher baseline, what was a once-a-century event will almost certainly become a more common occurrence as it takes less and less storm surge to push swollen oceans onshore.

Not only will future New York flood more often, but it will flood in far more places. The best place to see this is on the city’s own Flood Hazard Mapper, which can helpfully be customized to project any of a number of different future scenarios. For sea level rise, the projections don’t look too dire even when mapping the most pessimistic projections of high tide lines, though by the year 2100 (shown as the lightest pink), areas like Coney Island, the Rockaway peninsula, and Red Hook are being subjected to twice-daily deluges:

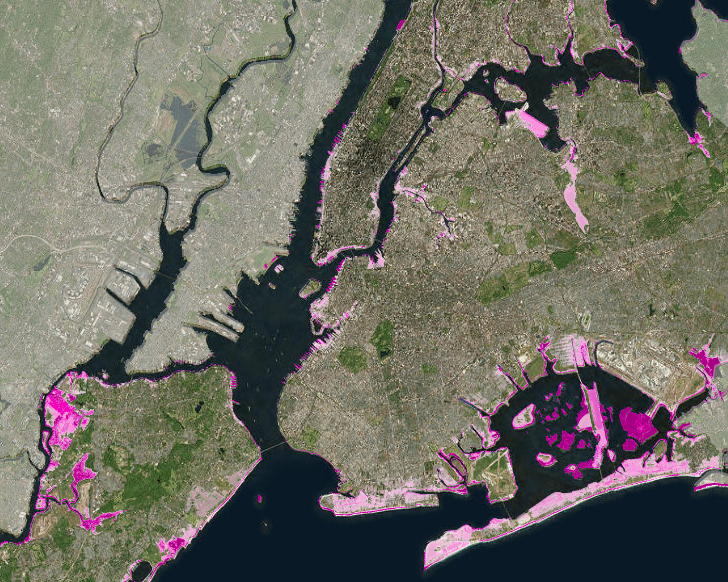

Looking at storm surge, though, is another matter. Here’s the medium-case scenario for a once-a-century storm, through 2100:

It’s predictions like this that have waterfront residents wondering what will be left of their neighborhoods by the end of the century, and what the city can possibly do to protect them.

“We’re screwed,” says Sanoff. “There’s no other way to put it.”

Exactly how much money the city is spending on shoring up waterfront areas is a bit dicey to calculate. Mayor Michael Bloomberg pledged $20 billion in spending over 10 years on “climate resiliency,” including building or rebuilding housing and city infrastructure that could withstand a 21st-century climate.

It’s a number that Bavishi reiterates: “We are implementing a multi-layered resilience strategy citywide, investing $20 billion.” The outlays, she explains, comprise a diverse list of projects: upgrading buildings and the building code, outreach and education around flood insurance, hardening infrastructure, protecting coastline, and “investing in neighborhoods” to promote “social cohesion.”

How much of that money has actually been spent — or even allocated by city, state, or federal sources — is less clear. The city budget scatters resiliency funding throughout the city’s various agencies, and lumps it together with “recovery,” which goes to rebuild from past storm damage, not necessarily protect against future flooding. There’s a “fine line between resiliency and recovery,” explains Independent Budget Office analyst Elizabeth Brown. “If you rebuild a boardwalk, hopefully you build it in a resilient way.”

While both types of spending are coordinated via ORR, keeping track of budgets is another story. ORR spokesperson Phil Ortiz says the office has a “resiliency portfolio totaling over $20 billion of committed funding.” (This is all separate from the mayor’s announced $10 billion downtown Manhattan shoreline project and the post-Sandy Build It Back initiative.) But he says there’s no central clearinghouse for how much is being spent on what, beyond providing an assurance that all the money is going to “projects that address climate risks.”

In addition, the city has also worked to incorporate anticipated sea-level rise into planning documents and building codes. Starting in 2017, the ORR began issuing Climate Resiliency Design Guidelines that spell out the ways in which city capital projects should take into account future climate change, from higher sea levels to hotter summers. The city’s building code has also been updated to encourage flood resistance and to incorporate updated flood maps; during Sandy, FEMA’s 30-year-old flood maps had proven vastly insufficient to the task, leaving many residents unprepared for the scope of storm surge.

The city’s approach has been to seek a “holistic response” to climate risks, says Bavishi. “Sandy exposed that climate vulnerabilities don’t exist in isolation. Whether it’s the presence of environmental hazards or inadequate infrastructure, or other challenges the city faces, climate risk makes those things worse.” In response, she says, “we’re really reenvisioning the waterfront as we attempt to find a solution.”

The city’s revised approach can be seen in its proposed rezoning documents for the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn. The city’s draft zoning proposal includes an entire section on “flood resiliency,” including requirements that residential units be built above flood levels (and raising of waterfront land be encouraged as well), that at-grade non-residential uses be “dry floodproofed (sealing the exterior of the building to make it water-tight),” and that drainage issues be assessed in light of potential new development.

These are all clearly good ideas, but there’s little in the report to indicate whether they will be sufficient to keep the ocean at bay. Significantly, zoning proposals can only affect new development and renovations — which could end up leaving the neighborhood with a mix of resilient new buildings and flood-prone older ones.

That’s a concern, says Katia Kelly, author of the Gowanus blog Pardon Me For Asking and a member of an EPA-led community advisory group for the area. Kelly has looked at the resiliency programs the city Department of Environmental Protection and state Department of Environmental Conservation have proposed, and is less than impressed.

“They’re all things that we should do, but the better alternative would be to go ahead and to retreat from the waterfront,” says Kelly. “But unfortunately that’s not at all what the city or the state of New York seem to be doing.”

One issue Kelly raises is that flooding doesn’t only come from the sea, but also from the sky. The Gowanus Canal, she notes, is an artificial canal built to drain the neighboring uplands of Park Slope and Carroll Gardens, which were originally separated by a vast low-lying swamp. “Right now, pretty unimpeded, some of the rainwater can flow down 2nd Street, for example, and drain into the Gowanus Canal,” she says.

If the city erects berms and other raised structures along the canal to defend against sea level rise, Kelly worries that will only cause rainwater to pool behind the raised sections, exacerbating the flooding that already plagues basements in the neighborhood. Already, the Lightstone luxury residential development that opened on Bond Street in 2016 raised its entire site, including the bed of 1st Street, by about ten feet under post-Sandy development standards, she notes. “That’s only on one side, but if you do it all the way around the Gowanus Canal, that could be a problem.”

Kelly says local residents have asked the Department of City Planning, as well as local councilmember Brad Lander, to conduct a hydrological study of the impact of greater development in Gowanus, but haven’t gotten one: “They basically said, ‘Oh, we’ll wrap it into the Red Hook study.’ And nothing really happened.” The city, she says, is “hellbent on building.”

Kelly has particularly called out Lander, who soon after Sandy issued a letter to the Lightstone developers asking for them to withdraw their application on the grounds that “it would be a serious mistake for you to proceed as though nothing had happened, without reconsidering or altering your plans, and putting over 1,000 new residents in harm’s way the next time an event of this magnitude occurs.” More recently, the councilmember has endorsed the city’s plans for high-rise developments in the neighborhood as “on the way to getting the balance right.”

Some waterfront residents have also expressed concerns that newly raised land could put neighboring unaltered areas at risk of seawater flooding. Ortiz says that the city has conducted hydrological analyses that show that seawater displacement into surrounding areas would be “negligible” — “it is essentially absorbed back into the vast volume of water in the East River/New York Harbor” — but the ORR has not made these studies public yet.

And then there’s the question of how fortified islands of new development would survive in the wake of a future storm.

“The new developments that are coming in are supposedly resilient — that means that they have some removable flood barriers on their ground-floor retail,” says Sanoff. “But what happens when we get the order to evacuate? Are all these new thousands of people going to be ordered to evacuate too?”

If not, she says, “when the storm waters recede they’re going to be in the same pickle as the rest of us: There’s going to be no safe food supply, there’s going to be no power; if you’re in a high rise, there’s going to be no water; and even if your building does have an emergency generator, it might need gas or diesel, and you can’t get trucks through because the streets are all blocked — we had walls of sand 10 feet high [after Sandy].”

Kelly notes that elected officials have justified new waterfront development on the grounds that it can be used to create more affordable housing, which she agrees the city desperately needs. “But really, the place to put these units should be on dry land — like Park Slope,” she says. “But the people in Park Slope would never go for it. The land is too expensive.”

In the past, city officials have also offered a type of “in for a dime, in for a dollar” defense of encouraging development on the water’s edge. “When you look at a really dense city like New York—we have 115,000 or so people living on the Rockaways—retreat has huge implications,” Daniel Zarrilli, then head of ORR, told City Limits in 2015. “There are ways to flexibly adapt and invest to reduce those risks to manageable levels, given the risks we see for the foreseeable future.” In fact, he said then, the de Blasio administration may even permit denser residential construction in some areas to lure new development, because new buildings constructed to code contain better protections against flooding.

Azaroff, who has degrees in both architecture and environmental studies, has made a career of working with local governments worldwide to help anticipate future environmental disasters. He says that New York could learn a lot in particular from Japan, where since the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, government officials have wasted no time in making sure that people will be safe the next time around — even if it takes “literally moving mountains.” The coastal city of Sendai, he notes, has relocated thousands of households away from the ocean to new, denser housing complexes; the 11,000-person town of Onagawa has raised its entire downtown by 15 feet, while relocating residents to higher ground being carved out of the surrounding hills.

“They spent over half a trillion dollars,” says Azaroff. “They were hit a year before Sandy, and they have largely completed all of this work.”

New York City’s strengths so far, he says, have been in improving existing infrastructure: shoring up beaches with fresh sand, repairing bulkheads, hardening ConEd facilities. He gives it worse grades on big ideas needed for long-term planning, such as the previously announced Big U plan for earthen berms to protect lower Manhattan, a project that received $335 million in preliminary funding back in 2015 but never moved forward, and has now been displaced by de Blasio’s scheme to build new land ..

Any long-term solution, though, may mean not just holding back the water, but retreating from it. The New York City Panel on Climate Change, notes Azaroff, has predicted that under a worst-case scenario where the Antarctic ice sheet melts more quickly, the city could face nine feet of sea level rise by the end of the century — a water level that would permanently submerge entire neighborhoods, including all of Coney Island, and much of Long Island City and East Harlem.

“If we are looking at that honestly, how do we accept the water in those areas, and what changes need to be made there?” he says. “Should people be living there? We should be upzoning other areas and really looking at how we begin to migrate neighborhoods into other areas.” Despite the Army Corps of Engineers’ current efforts to look into erecting enormous storm barriers, he says, “quite frankly, we don’t have a plan that is going to build seawalls around all of south Brooklyn and into the Rockaways and into those places, because it doesn’t make sense — from all standpoints of economy, of ecology, of environmental impact, it just doesn’t work.”

Instead, says Azaroff, New York should be looking at returning more waterfront areas to wetlands and other natural “sponges” that can help absorb storm surges when they hit. In Japan, the government has replanted coastal forests; in the Netherlands, retreat has taken the form of “depoldering,” which relies on decommissioning polders, undeveloped land reclaimed from the sea and protected by dikes.

But with no polders available to re-flood and a built-up waterfront, New York City is limited in how much it can do to retreat from the sea. Bavishi says that voluntary buyouts of homeowners will be an “important tool”; so far they’ve been largely limited to a few communities along Staten Island’s south shore. And especially along the East River waterfront, new luxury development will likely make future buyouts prohibitively expensive.

“Our issue is that we have 400,000 people living in those zones that are at the greatest risk,” says Azaroff. “Yet most of the large infrastructure proposals are focused on lower Manhattan.” The current wave of city upzoning to allow for denser construction — at least, everywhere but in high-income neighborhoods — could help, he says. “But is that upzoning part of a greater strategy of saying, hey, we already have people that will need to move to new places?”

The other concern about moving entire populations, of course, is that some neighborhoods (or some neighbors) would end up getting deemed more worthy of relocation — or protection — than others. The NYC Environmental Justice Alliance has already railed against the city’s plans to spend $10 billion building out lower Manhattan into the East River to protect against storm surge, while only spending $45 million toward a pilot project to protect Hunts Point market in the Bronx, a major element in the city’s food supply system.

The Regional Plan Association, in its Fourth Regional Plan released in 2017, has called for buyout programs to “return to nature all unprotected areas subject to permanent flooding from one foot of sea-level rise by 2040, and three feet of sea-level rise by 2075,” as well as placing a moratorium on new development in flood-prone areas by 2020.

“There are places we won’t be able to protect no matter what we do,” says RPA vice-president for energy and environment Rob Freudenberg. “We’ve figured out ways to accommodate coastal storm flooding” — such as by elevating homes — but “there will be places that will have everyday high-tide flooding, and that’s not a situation you can actively live in.”

The problem, Freudenberg acknowledges, isn’t just coming up with the unknowable billions of dollars that will be necessary to relocate communities, but also what will happen to lower-income residents, especially as their property values plummet as seawater begins to lap at their doors. “It’s almost built in with inequity,” he notes, especially with so much public housing having been concentrated in what was at the time cheap land along the shore. “We don’t know how to buy out public housing — there’s no system in place to do that.”

None of the choices facing New York — barring a sudden global decrease in greenhouse gases, which isn’t looking likely — are good ones, and many future New Yorkers are certainly going to be, as Sanoff says, screwed. But Arazoff still has hopes that even a vastly different city can remain a livable one, if we begin planning now.

In Japan, he notes, disaster shelters are instructed to ask the displaced not only their names, but also those of 10 families that lived near them. This means if it’s necessary to relocate residents, officials can at least ensure that neighbors are kept together. And that, he believes, could be more important than saving particular buildings, or even entire neighborhoods.

“If you want your neighborhood back, is it really the bakery on the corner, or the person who runs the bakery?” he asks. “If it’s the person who runs the bakery, we can solve these things.”

4 thoughts on “As the Sea Rises, Will Resiliency—Rather Than Retreat—Be Enough to Save Waterfront NYC?”

Thanks for the projections. In 2100 I’ll have harbor-front property. My great grand-children will be delighted.

Pingback: Benefits Of Investing In Climate Adaptation Far Outweigh Costs, Commission Says | PopularResistance.Org

It seems like the year 2020 is only an appetizer for more global events to occur. The article says that even reducing green-house gases is unlikely at this stage to stop cities from being largely compromised by global warming. I am American, 55 years old, and I live in Shenzhen, China. Nearby Guangzhou is considered highly vulnerable to early-stage rise of sea levels. It is good that mayors like Bloomberg and Blasio are putting some thought and resources into it. Today I was thinking of the migration of people from New York to other parts of the country. The Netherlands is taking it the most seriously. But from the article, I take away that the people now in charge do not enough for the people who are now being born or who are millennial youth and such. More so, from the year of 2020, where we have slowed down carbon emissions by being acted upon by an unseen force, we still seem to crave a Starbucks paper cup coffee go down and fire up our desire for more and more development. All anybody ever talks about is dealing with the economic reality of feeding oneself or their children. I hope that people can do something through the democratic process. And not bicker and name call and participate in partisan identity politics. These are my concerns and my voice. I used to run an event called Conversation Cafe in the U.K., and it was a way to exercise democracy and make friends at the same time by talking. We do not come together as a species, enough in my opinion, to talk in a heartfelt way. Bob Dylan famously said, The Hour is Getting Late. That is not prophetic. It has happened in 2020.

Good Lord if we still have the time and resources why are we not acting now and right now this second.

I have learned we may face complete social collapse within the next two decades if we do not take this thing head-on.