Adi Talwar

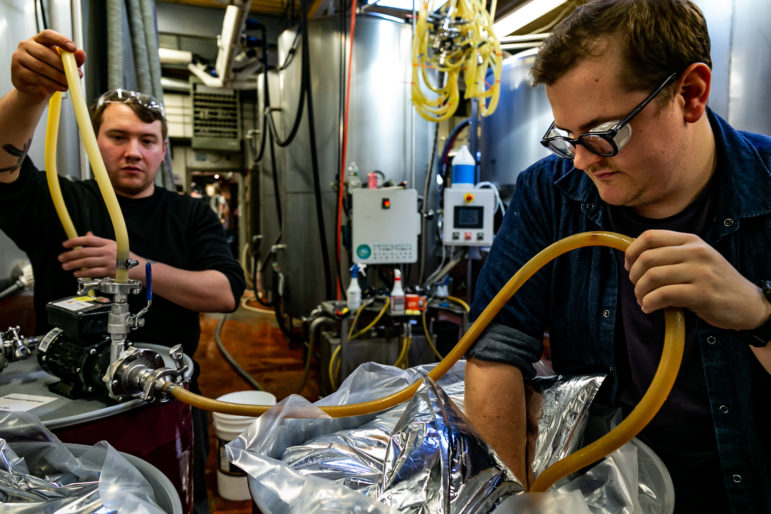

Intern Eric Nelson (left) and Lead Brewer JD Linderman pumping grape juice from a barrel to a fermenting vessel at the Sixpoint Brewery, located in Red Hook, an area that could be impacted by the Opportunity Zones program.

Days from now the Internal Revenue Service is expected to release a new set of regulations on Opportunity Zones, a new federal program that provides tax benefits for investments in economically depressed communities.

The Opportunity Zone tax program, shoehorned among the thousand pages of the Trump administration’s 2017 Tax Plan, has left New York housing insiders with little knowledge on what impact the city could see in neighborhoods presently facing development changes. Meanwhile, area investors are showing interest.

Less than a month after President Donald Trump was inaugurated, Senators Tim Scott (R-SC) and Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Congressmen Pat Tiberi (R-OH) and Ron Kind (D-WI) introduced the “Investing in Opportunity Act,” a bipartisan bill designed to incentivize investment in economically distressed communities across the country. Its sponsors said it would galvanize the creation of investments in small businesses, developing properties, local infrastructure projects and other activities to create new opportunities for local residents in geographically-targeted locations.

The Opportunity Zones program, administered by the IRS and the U.S. Treasury Department, provides preferential capital gains tax treatment—a option to avoid or minimize taxes—for investments within designated low-income census tracts. The low-income census tracts are based on federal census tracts which must have 50 percent of households with incomes below 60 percent of the Area Median Gross Income or have a poverty rate of 25 percent or more.

The tax treatment also applies to investments in areas contiguous to low-income census tracts.

A capital gain is the profit from the sale of an asset such as a business or parcel of land. An Opportunity Zone investor can take their capital gains from other activities and invest that money into what’s called a “Qualified Opportunity Zone Fund,” which is a partnership or corporation that then invests in eligible property located in an Opportunity Zones. (The only investments Qualified Opportunity Zone Funds cannot make are into “sin businesses” such as casinos or liquor stores within opportunity zones.)

At the very least, investors in OZ funds get to defer taxation on the capital gains that they invest in the first place. Then, the longer the investor keeps his or her money in the fund, the greater the tax benefit — a 10 percent break on capital gains taxes for investments held for five years, a 15-percent break for investments held for seven years and a total wipeout of capital gains taxes on investments held for at least 10 years.

It could be a lucrative deal for investors. What it means for residents is less certain, because the OZ program appears different from geographically targeted programs that have come before.

“There are a lot of place-based incentive programs out there. So there may be another fund somewhere that is structured like this,” says Scott Eastman, federal research manager at the Tax Foundation and co-author of a recent report on the emerging program. “But the benefits to economically distressed communities, those are very uncertain because there is not enough information to say they work,”.

The Tax Foundation report concluded the program will attract at least some investment to low-income census tracts designated as zones. However, how effective Opportunity Zones program will be at “improving the lives of low-income people in economically distressed communities” is unclear and there is the danger that if could “actually be counterproductive to generating sustained development in these communities” because of the lack of regulations. Adding to the uncertainty: Little data exists about the impact of federal Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Zones or Renewal Communities—the previous generation of federal, place-based incentive programs.

Where are the OZs?

Across the country, there are 8,700 certified Opportunity Zones and of those the U.S. Treasury identified more than 2,000 low-income census tracts in New York State as potentially eligible for the Opportunity Zone designation. The Cuomo administration was then allowed to select 25 percent of these low-income tracts to actually be part of the program. New York says it submitted its 514 tracts based on recommendations from the states Regional Economic Development Councils, local input, prior public investment and their perceived ability to attract private investment. The state sent their selections to the U.S. Treasury Department last April.

New York’s Opportunity Zones are spread statewide. About half are in the five boroughs.

In Manhattan, there are 35 OZ tracts including the greater Inwood area, parts of West and East Harlem, a section near East 25th Street and parts of the Lower East Side. In the Bronx, there are 75 OZ tracts, including most of Hunts Point, Mott Haven, Morrisania and Highbridge.

Brooklyn has 125 OZ tracts in neighborhoods such as Red Hook, Williamsburg, Seagate, Bayridge, Bushwick and East New York. In Queens, there are 63 (Long Island City, Whitestone, southeastern Jamaica, South Ozone Park and parts of the Rockaways) and Staten Island’s eight tracts are all on the North Shore.

Map courtesy NYS ESD

The concerns about OZs

The impact New York communities could see from the Opportunity Zones program is not clear enough for housing experts who have raised concerns about how the tax program could drive displacement through speculative investments in those low-income communities. But there is also sense that the program could offer real benefits.

According to senior policy fellow at the NYU Furman Center Mark A. Willis, the tax provision does not require any progress reports from the communities in Opportunity Zones so there will be little to no way to assess its results. However, there could be benefits for communities in low-income census tracts if it helps to drive down costs for affordable housing developers in those areas, and therefore allows the city’s subsidy dollars to go further in creating more affordable housing elsewhere.

In February, Lori Chatman, president of Enterprise Community Loan Fund, testified at a IRS public hearing on Opportunity Zones in Washington D.C. Enterprise announced its own qualified opportunity zone fund and aims to raise to raise $250 million for investments local main streets and entrepreneurs across the Southeast. Chatman said in her testimony that Opportunity Zone investments will be the most impactful when paired with existing federal, state and local community development initiatives, such as the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

But she also shared some concerns. One was that if IRS metrics exclude land value when calculating whether or not an Opportunity Zone investment had made real improvement to a parcel, speculators could be rewarded for merely grabbing and holding onto valuable land. She also thought real-estate investments should be held to a higher investment .performance standard than others

According to a letter by the de Blasio sent to the IRS in February, with contributions from the city’s Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) and NYC Economic Development Corporation, the city shares some of the same concerns as advocacy groups and urban policy experts. The letter stated that without a pertinent regulatory system in place the tax program could also incentivize predatory and risky investments in already distressed communities,

“Opportunity Funds have the potential to build on the successes of existing programs and to complement the public-private partnership model, but the positive benefit will only be maximized if the funds are regulated,” it read. “Without an appropriate regulatory structure in place, Opportunity Funds could incentivize predatory and risky investment that competes with rather than promotes the public interest, such as the need for affordable housing, economic and community development, hospitals, and schools.”

In the letter, the city recommended strong guardrails for the tax program and made four major recommendations. The first was to monitor the tax program by tracking the impacts of the tax benefits so investors can share best practices as well as “ensure investments serve the communities that need them most.” The second recommendation was to show complete transparency by having Opportunity Funds and their investments registered in order to assure the Funds are contributing alongside local government programs for low-income communities. The third suggestion was a well-coordinated structure between federal, state and local government for guidance and clarification so Opportunity Zones could work in conjunction with existing local tax benefits and programs to create more effective public and private partnerships. And the final ask from the city to the IRS was additional clarification on how Opportunity Funds will work with local legal structures.

Adi Talwar

Dwight Street entrance to the Sixpoint Brewery in Red Hook Brooklyn. One question about the Opportunity Zone program is whether it will incentivize job-generating investments in going concerns or merely encourage real-estate deals.

Who wants to be in the OZ?

Brad Molotsky, a real-estate attorney and partner at Duane Morris, has been pretty busy lately. He has been traveling across the tri-state area giving presentation to interested investors and speaks at conferences about Opportunity Zones. Molotsky says anyone can invest in a qualified opportunity fund. The interest has grown dramatically over the last few months, especially within the real-estate industry.

Molotsky said Senators Scott and Booker’s original goals were job creation and affordable housing. However, he acknowledges the fear of displacement and gentrification. “The potential is a bunch of development that a neighborhood is not interested in or not ready for. It could very well happen. And then what are the ramifications for that? They can’t stop it. So the issue becomes, what’s your zoning? What does the zoning allow you to do, right?”

A particular concern is whether true affordable housing, which offers low margins to developers and sometimes a long wait for that payoff, could demonstrate a “substantial improvement” within the 30 months the OZ program requires. Still, Molotsky points out: “We have to remember that there are hundreds of communities across the country that would give their left arm for this type of investment..”

Brooklyn’s Terra Commercial Realty Group founder and CEO Ofer Cohen and his partner Daniel Cohen said they see interest in Opportunity Zones from those already in their industry. “What we are seeing a lot in the market right now are developers or investors that are already in the business of buying real estate. It’s what they are doing anyway and it just changes they way get their capital,” said Cohen.

According to a Real Analytics report, many qualified census tracts were “already transitioning before the program,” and, reinforcing housing advocates’ concerns, in some areas land sales started spiking even before preliminary OZ regulations were set by the IRS in 2018. “With over 30% of commercial property in the NYC Boroughs now in a designated zone, the additional boost of investment from Opportunity Zone funds threaten to propel these markets into a new orbit,” the report warns.

But not all OZ investors are exclusively interested in real-estate development. Canadian Zale Tabakman, a former computer engineer, believes the Bronx is an ideal place for a vertical farm. Tabakman’s goal is to combat food deserts with his company Local Grown Salads, which operates self-contained vertical farming units. He wants investors to fund his company so he can operate vertical farms in Baltimore and the Bronx—to start.

“Opportunity Zones were invented for me,” boasts Tabakman. “I can create jobs. I’m doing clean work. I can create food in food deserts.”

Inconclusive reports and the lack of regulations:

Opportunity Zones is not the first place-based tax incentives program the United States has seen. Since the nineties, Congress has passed three different measures involving federally designated geographic areas displaying high levels of economic distress and where businesses and local governments could receive federal grants and tax incentives. According to the Congressional Research Service report, Congress remained interested in these programs “despite increased concern over the size and sustainability of the long-term budget outlook.”

The concept of place-based tax incentive programs originated in the mid-1970s in Great Britain and made its way to the United States. In 1980, an Enterprise Zone bill was introduced by Republican Representative Jack Kemp and while his federal legislation was not enacted, several states did implement enterprise zone programs.

The feds did get into the game with empowerment zones (EZ) which ran consecutively from 1993 until 1999. Another program, Enterprise Communities ran from 1993 until 1997, and a third program called Renewal Communities ended in 2000. The three programs had different benefits and eligibility criteria. According to a 2011 Congressional Research Service report, an estimated $1.8 billion in grant incentives was spent on the three programs.(Under the Obama administration, the government saw a related but different set of place-based initiatives such as Promise Neighborhoods and Choice Neighborhoods.)

Those earlier programs featured significant regulation. For example, a business’s tax benefit might be tied to whether their hires lived in the neighborhood or fixed their storefront. Currently, regulations such as these do not exist for Opportunity Zone investors. Molotsky says he expects the next announcement from the IRS on Opportunity Zones to offer more detailed guidance and regulations on the new tax program.

According to a 2010 U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) report, while the place-based tax incentive programs helped jump start businesses and finance some local projects, the lack of data on their actual impact was inconclusive.

But much of the uncertainty about Opportunity Zones is not about how past programs performed but rather the unique features of this new initiative. Molotsky says investors have expressed some concerns such as how they might connect with people who are already interested in starting or growing small businesses those low-income census tracts. Another question Molotsky gets asked is whether a business located in an opportunity zone but operating outside it—such as an Internet business—would qualify. Small details such as those are not defined in the federal regulations for Opportunity Zones, at least so far.

At least so far, “It’s all self regulated. So that’s good if you’re the business. It’s less good if you’re interested in specificity and clarity and oversight,” he says.

One thought on “New Federal Tax Program for Depressed Neighborhoods Stirs Hopes and Concerns”

total benefit for the rich real estate predators