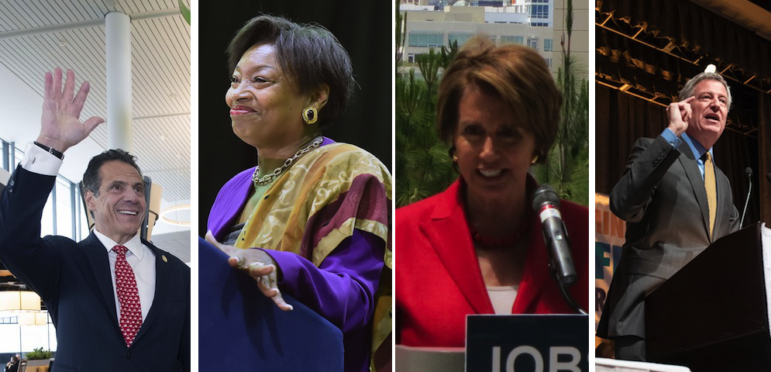

Office of the Governor, U.S. House, Mayoral Photo Office

A few of the people who will shape the 2019 agenda that affects New York: Gov. Cuomo, Sen. Stewart-Cousins, House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi and Mayor de Blasio.

The voting machines are back in storage, the “Vote Here” signs are gone, and politics in New York have entered the interregnum between Election Day and the start of the new term in Albany, when a newly-Democratic State Senate and a re-elected Democratic Assembly majority and Democratic governor will begin to set the direction of the Empire State in 2019—while a new Democratic majority in the U.S. House of Representatives vies with a Republican U.S. Senate and President Trump over where and how to steer the nation.

The rhetoric, posturing, and proposals of the campaign will give way to the rhetoric and posturing—and, ultimately, policymaking—of government. It’s too early to know how the new balances of power will play out, but some of the newly powerful or electorally emboldened are already giving indications of some of their priorities, which, in combination with campaign trail promises, form the outline of what to expect in Albany in the year ahead. Governor Andrew Cuomo and legislative leaders have quickly provided a sense of what they plan to tackle first and what might be on the backburner as the state governing session begins in January.

“I did better than I had done in my previous election which is normally unheard of,” Cuomo said the day after the election, on WVOX radio, “but we also won the Senate, which is very important and I worked very hard to make that happen, which it allows me to get all sorts of things done that we haven’t done before.”

As is always the case, so much of what happens in the state capital will impact New York City, and though there were no elections for city-level positions this year, those who live and work in the city have a great deal at stake as the new state government takes shape. Mayor Bill de Blasio and others are already laying out their priorities for 2019 in Albany, where the mayor and other city Democrats hope the atmosphere will be more friendly toward the five boroughs than in the past.

“[T]he fact that we not only have a Democratic majority in the State Senate but a resounding Democratic majority is going to allow for a host of progress for this state and going to allow some really important initiatives to finally be acted on that we’ve been waiting for, for years and in some cases decades,” de Blasio said on Wednesday. “Most especially reform to our election process, campaign finance reform, finally getting a solution for the MTA. Huge changes could come from the fact that we now have a strong, clear Democratic majority in the State Senate.”

Still, much will happen at the city level in the year ahead that is not necessarily a product of Albany decision-making. Even as he seeks legislative and funding changes in the state capital, de Blasio has city challenges to address, programs to implement, and major decisions to make. There is a Charter Revision Commission exploring sweeping changes to how city government operates, and there will be a handful of elections in the city, starting with a special election for public advocate, likely in February.

There will be a great deal at stake in 2019. Advocates, organizers, strategists, and elected and appointed officials have already provided a long list of topics and decisions that will come to the fore next year. So City Limits, Gotham Gazette, and other partners are teaming up over the next eight weeks to explore major policy issues where action is expected over the next 12 months.

Each week we will bring you an in-depth look at one issue area with comprehensive reporting, broadcast interviews, opinion columns, and other features to provide insight into the policies, politics, and people involved and set the stage for what will be an incredibly important year in New York City, New York State, and national politics.

First, an overview of what’s on hand.

Albany

The story begins in Albany. The 2019 landscape in the state capital will be unlike anything seen in roughly a decade: full Democratic control of the executive and legislative branches. This time around is likely to be far more functional than last, when the Senate Democratic conference quickly devolved into chaos and a weak governor was unable to keep his party-mates from disgracing themselves (several of those involved have served time in jail) and bringing legislative business to a long halt.

In 2019, Cuomo enters a third term with wind at his back, major infrastructure projects in motion, and a long to-do list; while Democratic majorities in the Assembly and Senate finally get the opportunity they’ve been waiting for to pass an agenda repeatedly stalled by Republicans in the upper chamber.

The questions that hang over this new arrangement include to what extent various Democrats with varied priorities are able to agree upon an order of operation and the specific details of policies they’ve championed but never actually had the power to pass into law without compromising with Republicans. Expected Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and others have already given indication of what they see as the top priorities with widespread agreement.

Cuomo, who has appeared mostly happy with a split Legislature, now faces the challenge of dictating terms to legislative majorities that may want to move faster and further left than he’s comfortable with, though Democrats also know that the next legislative elections are now less than two years away and their members from swing suburban districts need to be especially careful with ‘pocketbook’ issues. Taxpayers across the state will soon be adjusting to the full new reality of federal tax reforms, which capped state and local deductions and are of great concern to suburban homeowners. Plus, the state’s current “millionaires tax” is set to expire in 2019 and Cuomo hasn’t yet indicated his stance on renewing it, even as he faces upcoming budget deficits.

“I am a suburban legislator,” Stewart-Cousins of Westchester told Long Island-based Newsday. “I am very proud that New Yorkers have elected many great suburban legislators to take their place in the Senate Democratic Majority.”

Cuomo has been clear that he plans to continue the fiscal restraint and center-left governance of his first two terms. At the same time, he’s poised to push through many significant policies his critics have blamed him for not delivering, while addressing the twin crises of his second term: the failing New York City subways and the corruption that has continued to plague state government, recently in the governor’s own inner circle.

Cuomo wants to keep state spending increases to roughly two percent annually, to keep an annual cap on property tax growth everywhere outside New York City, and to take steps to mitigate the effects of federal tax reform, especially the new cap on state and local deductions. But he also has a lengthy professed agenda for 2019 and his larger third term, including voting reform, additional gun control regulations, the Child Victims Act, codifying Roe v. Wade abortion protections into state law, the Dream Act, the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act (GENDA), and more. For the most part, the policy agenda Cuomo has laid out, which is noticeably light on new spending, should not be a heavy lift in either house of the Legislature with both under Democratic control.

There may very well be areas of conflict, however, even if legislators stay away from raising taxes or pursuing policies like single-payer health care that Cuomo has thrown cold water on. These include government ethics and campaign finance reform, funding the MTA, rent regulations, education funding, charter schools, criminal justice reform, and others. How to move the state ahead in combating climate change may also be a source of disagreement in terms of degree.

The governor knows he must—and has promised to—move ahead with congestion pricing for Manhattan travel as part of funding the MTA and the Fast Forward subway modernization plan that is ballparked at around $35 billion. It’s unclear where the rest of the needed money will come from, though Cuomo has already indicated he expects the New York City government to kick in more (de Blasio continues to call for an additional tax on high-earners, which Cuomo has mocked). The governor even got several Senate candidates on Long Island to sign a pledge that they’d squeeze the city for more transit money—not the only episode of the fall campaign to raise the possibility that Cuomo is readying to continue to hold sway over policy-making in Albany no matter how other pieces may shift.

The governor is also frustrated with hearing about his failures on government ethics and campaign finance reform, and will likely look to put that talk to bed by the time a new state budget is passed at the end of March. The details of any such deals will be closely examined for whether they truly advance the causes of good government and provide the best possible circumstances for both preventing and punishing corruption.

A major unknown is whether some of the newly elected State Senate Democrats, especially those on Long Island, will feel more beholden to Cuomo than to the conference itself, and help him restrain the larger group. On the other hand, it is unclear how the new group of state senators who defeated members of what was the Independent Democratic Conference, some of whom cross-endorsed with Cynthia Nixon in her challenge to Cuomo, will approach the governor and raising their voices within the Senate majority.

During a Wednesday appearance on Spectrum’s Capitol Tonight, Stewart-Cousins was asked about unifying her new conference and finding agreement. “So people understand that there’s a lot of great hope in our ascension to power,” she said, “and in order to really fulfill those hopes, we have to move as a body. That means we’re going to have to find ways to get to the desired end…We must consider that it is one New York, but there are a lot of different places, a lot of different regions and areas and needs and interests, and if we do our job right we will be able to manage and take care of all of it.”

Democrats in the state Assembly, which is dominated by New York City members and led by Speaker Carl Heastie of the Bronx, may be itching to enact an agenda they have repeatedly passed that has not had Cuomo’s full support and that is not necessarily the same agenda as the new Senate Democratic majority. Assembly Democrats have spent years passing one-house bills and budgets advancing progressive priorities, including things like single-payer health care, higher taxes on top earners, tighter rent regulations, and sweeping criminal justice reforms.

Still, there is much that Democrats in the Assembly, Senate, and governor’s mansion agree on and will all-but-certainly find common ground to pass, starting with a handful of policies that Cuomo, Stewart-Cousins, and Heastie have already mentioned since the election results came in: voting reform, women’s reproductive choice, gun control, and more.

“There have been measures that I could not get done with a Republican Senate and I believe they were short-sighted,” Cuomo said Wednesday. “…And I worked so hard for a Democratic Senate, because these are pieces that I believe are essential to really move this state forward.”

“We need ethics reform and there’s no reason not to pass it,” he continued, mentioning making legislative positions full-time with no outside income, campaign finance reform (including closure of the LLC loophole), and voting reform, including early voting.

“The women’s right to choose has to be protected,” Cuomo said, referring to the Reproductive Health Act, which would codify Roe v. Wade into state law. He also mentioned the Dream Act, “gun safety” legislation, which would likely include a “red flag bill” to remove guns from the homes of potentially troubled young people and extending the background check wait time from three to ten days.

All of the issues listed by Cuomo are ones that Stewart-Cousins, members of her conference, and Heastie have mentioned in the first days after the election as top priorities.

While Cuomo appears ready to knock down any criticism that he is not a ‘real Democrat’ and create additional buzz around a possible presidential run, he always wants to move on his terms. A deal-maker who leverages his counterparts, the governor has clearly been sizing up the new dynamics he’s facing ahead of the state budget session that will kick off in January with his State of the State speech and Executive Budget presentation. Discussing the facts that he received the most votes of any governor ever and won this year by a bigger margin than in 2014, Cuomo said Wednesday that it “helps practically in governmentally when you have a larger mandate electorally, the other elected officials know you’ve literally come into government with a stronger hand, and having a larger victory helps you governmentally, I believe that.”

And even as Cuomo has pledged to serve another four-year term and there are very serious questions about his viability as a presidential candidate, he has regularly stoked the flames and after another resounding electoral victory, may be poised to flirt even more explicitly with a run for president.

One possibility is that Cuomo focuses intently on moving an aggressive progressive agenda through in the first few months of the Albany year, then takes his new list of accomplishments to a few of the necessary stops on a presidential exploration tour, such as New Hampshire.

Another uncertainty for the year ahead is exactly how Attorney General-elect Letitia James approaches her new role. James, a Democrat who is currently the New York City public advocate, will vacate that position and take charge of a vast and immensely powerful legal office. She has promised to continue the aggressive approach the office of attorney general has taken to President Trump, his administration and his other enterprises, while also taking on criminal justice reform in New York and working to root out public corruption, among other aspects of the role she has said she will embrace. In the face of skepticism about her closeness to Cuomo and other Democrats, James has promised to be an independent voice and to pursue wrongdoing wherever it may be.

There is no speculating that much of New York City’s policy agenda depends on legislative action in Albany. Speedy trial and bail reform legislation seen as vital to the effort to close Rikers island jails will be a top priority for progressives in the capital and City Hall. And the renewal of rent regulations presents a major opportunity to reduce the displacement pressures that dog de Blasio’s rezoning and development plans. There is almost guaranteed to be city-state tension in 2019 over funding the MTA, among other policy and budget issues.

Asked the day after the election about his top priorities for the Albany year ahead, de Blasio said, “One: strengthen rent regulations, protect affordable housing. Two: fix the MTA, provide a permanent funding source for our subways and buses. Three: continue our progress on education funding and on having the power to keep fixing our schools.”

New York City

Under normal circumstances, 2019 would be a quiet year in city politics—an off-year between the 2018 statewide elections and the presidential race in 2020, with municipal elections a full two years off in 2021.

But circumstances are not normal. A a citywide official is leaving her office vacant, a veteran district attorney is retiring, and big decisions on everything from charter revision to jail-siting and neighborhood rezoning are due.

As is always the case in the years after statewide elections, three district attorney races are on the docket in the city. All five of the city’s sitting district attorneys are Democrats. Incumbent Darcel Clark in the Bronx, who was elected in 2015 with 80 percent of the vote, is unlikely to be threatened. Staten Island’s Michael McMahon won his post in 2015 with 55 percent of the vote, and could face a more competitive re-election contest. But the Queens DA’s race is shaping up to be the most dramatic affair, with incumbent Richard Brown—who ran uncontested in ’15 and has held his post since ’91—likely to step down and a roster of well-known names (City Council Member Rory Lancman, former Council Member Peter Vallone, Jr., Queens Borough President Melinda Katz, State Senator Michael Gianaris) in the mix of declared or potential candidates.

Letitia James’ victory in the race for attorney general means there’ll be a special election to fill the post of public advocate. Brooklyn Council Member Jumaane Williams, fresh off his campaign for lieutenant governor, and Bronx Assembly Member Michael Blake are already in the mix for that post, along with a couple of others like Nomiki Konst and David Eisenbach, and a host of other names are considered possible candidates.

The special election to select an interim public advocate will be a nonpartisan affair held in early 2019; the winner of that could then face a primary in September before a general election in November 2019 to decide who serves the remainder of James’ term. Worth noting: If someone currently in elected office wins the special election for public advocate, there will need to be another election to fill the slot the winner vacates. It could be a very special year.

Also expected to be on the ballot next November: the proposals from the City Council’s 2019 charter revision commission. The hearings and meetings (and behind the scenes machinations) that will shape those proposals will be a significant story to watch in the city next year, because the changes on the table next November could be the most significant in 30 years. Already, the commission has been asked to consider ambitious alterations to how the city does budgeting and land-use planning.

Critical housing policy decisions will come throughout the year. The city’s “Where We Live NYC” fair-housing planning process—a landmark examination of whether city housing programs have reduced or exacerbated segregation—is supposed to wrap up by the fall of 2019. A decision could come in the lawsuits over the fairness of the community preference policy and the property-tax system, and the property-tax reform commission empaneled by de Blasio and City Council Speaker Corey Johnson is holding its final first-wave meetings in later November and December and could issue a report soon—with whatever plan emerges subject to intense debate, as well as legislation at both the city and state levels.

Decisions on major neighborhood rezonings of Bushwick, Gowanus, and Bay Street are likely, with action on Long Island City and the Southern Boulevard area of the Bronx also possible. And the Council and mayor will render decisions on the plans to build new jails to replace the facilities on Rikers Island.

Meanwhile, the NYCHA settlement with federal authorities awaits approval—and NYCHA families await another winter and the potential for heat and hot-water problems. The federal criminal investigation of NYCHA and its decision-makers is not over and could produce more news, and some housing advocates will bring more pressure on the mayor to build new senior housing on NYCHA land rather than market-rate units. De Blasio may name a permanent head of NYCHA, or keep the interim leader, Stan Brezenoff, in place. The city will also be looking to Washington for more funding help for public housing, and may put forward a revamped long-term plan for NYCHA that accelerates the pace of development on under-utilized NYCHA land as a way to bring in revenue.

2019 is the year when the hit from the Trump tax plan’s capping of federal income tax deductions for state and local taxes will start to affect high earners—and it will be interesting to see if that encourages calls to rein in spending during the city’s budget process. As one business advocate notes, “Only a relatively small number of high earners have to relocate to lower tax states for NYC to suffer major revenue losses.” People in the top 1 percent – those in the 38,000 households making more than $713,000—earned about 35 percent of the city’s income and contributed roughly 44 percent of total income-tax revenue in 2016. But keeping budget growth modest will be challenging, with the MTA, NYCHA, and the public hospital system in need of major investment.

The city’s ability to implement the Fair Fares Metrocard subsidy program will be tested, and bus riders should get a glimpse of the newly redesigned bus routes coming under the MTA’s Fast Forward plan. The rollout of the school desegregation effort in District 15 will continue as New Yorkers get more of a sense of whether and how Richard Carranza will put his stamp on the school system.

The x-factor in all these stories is how much power Bill de Blasio will have to shape these critical policy decisions, all of which will help sculpt his legacy.

The mayor did little to define a second-term agenda before he was re-elected in a landslide a year ago, and he’s not done much to fill in those blanks over the past 12 months. His signature policy idea of 2018, the democracy initiative, has not had an auspicious start, though de Blasio did see the three ballot proposals from his charter revision commission approved by voters on Election Day. While the mayor has made substantive policy moves, on cybersecurity and guns for instance, they have been drowned out by a torrent of dreadful headlines about NYCHA, his school renewal plan, his beef with the Department of Investigations commissioner, and, of course, the “agent of the city” emails.

Some of that static is merely what comes with the territory of a second term in one of the toughest jobs in the country. But de Blasio’s unusually acrimonious relationship with the press, his feud with a governor who was just resoundingly elected for a third time, the rise of a less-cooperative City Council and the pre-2021 positioning that is already taking place among his partners in government could combine to irreversibly weaken the mayor years before he ought to look like a lame duck. While that might sound like good news to those who dislike de Blasio, the fact is the city’s interests in Albany or Washington depend on there being a strong figure in City Hall. Other players might claim some spotlight and gain some juice, but Bill de Blasio is alone at New York City’s helm for another 1,150 days. That would be a long time to be adrift.

Washington, D.C.

And then there’s Washington. The new Democratic House could move a legislative agenda to try to limit the impact of the limitations on SALT deductions, support infrastructure spending, shore up the Affordable Care Act, and take steps to thwart the president’s harshest moves on immigration—all of which would have direct impact on New York City and State. But with Republicans maintaining control of the Senate and the White House, Democrats will not be able to move anything through Congress without major compromise. It’s unclear who will lead the House Democrats or what their strategy over the next year will be: seeking a deal with centrist Republicans, or even with the mercurial president himself, to create new policy, or instead maintaining a more combative posture until the 2020 presidential election resets the country.

The Iowa caucus, after all, is only 15 months away.