W.W. Norton

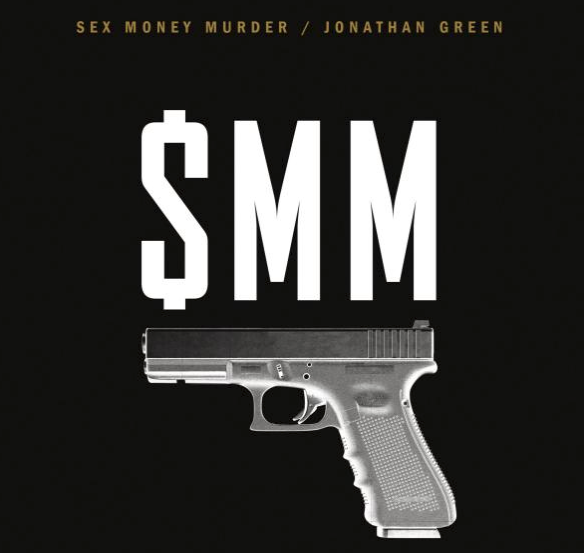

“SEX MONEY MURDER: A Story of Crack, Blood, and Betrayal”

By Jonathan Green

W.W. Norton. 413p. 27.95

My first experience with the criminal Bronx was in 1977. I was teaching at Fordham and had just stepped off the train from Manhattan at the Fordham station and was standing alone on the platform looking for the hole in the fence where I could climb up into the University campus rather than climb the stairs and come in the front gate. Suddenly two figures hustled across the footbridge over the tracks onto the platform and ran at me. Both wielded big knives which they pressed against my chest and throat.

I started to tell them that it would be bad luck to kill a priest; but they growled the only English word they seemed to know: money. They took my wallet, watch and keys and ran. I pursued them up the steps onto Fordham Road, hoping to find a policeman. Unfortunately I found two too late; they invited me to study the criminal suspects photo album at headquarters.

Both writing and reading Jonathan Green’s powerful book has been, and probably must be, an ordeal. In five years of research, apparently endless interviews with citizens of the Bronx, devoted police officers and some of the worst people on the face of the earth—drug dealers and killers, who, if New York had not abolished the death penalty, would be waiting on death row. Green has thoroughly and bravely recreated the hell of the Bronx in the 1980s and 1990s.

CityReviews

Books, movies, television and music of and about the city

Read more here.

Green sometimes adopts the style and structure of the novelist, but we know the characters. not by their legal names but by nick or code titles —Suge, Pipe, Pete, Crackhead, Big Bimbo, etc. First, the scene, where Soundview Houses’ 13 seven-story redbrick buildings fill two T-shaped sections. In 1988 Soundview had around 1,250 families, mostly black and Puerto Rican; three percent were white, 40 percent on welfare. And only 20 families had had at least two family members working. In late afternoon hordes of rats climbed out of the river and spread out into the neighborhoods.

The African-American young men — aged from 11 to mid-20s— soon organized themselves into a devastating gang, choosing the name of SEXMONEYMURDER to clearly express what their lives were devoted to. SEX sets the tone of their entertainment, streetwalkers in their bedrooms, women to boss around.

Family life as most people know it had little relevance. Suge’s mother couldn’t take care of him so she handed him off to his grandmother whose discipline could be brutal. To punish some broken rule, she caught him stepping out of the bathtub naked and lashed him with a whip. One day when Suge was talking with a buddy Pete on the sidewalk a sleek black car pulled up and a tall man with a boxer’s physique stepped out and summoned Pete. He opened the trunk and pulled out a gleaming motorized scooter which he presented to Pete and drove away. A few days later Suge asked Pete, “Who was that?” Pete replied, “That’s your father.”

MONEY There’s little discussion in this book of work, jobs, and even less on an education that might lead the young to productive lives. Their lives were built around a network of heroin and crack distribution that reached to other cities and states as well. They stole cars as readily as they would shop-lift a pack of cigarettes. Their pockets burst with rolls of $100 bills. The one possession most sacred, it seems, is the gun.

MURDER. The word “love” doesn’t fit in the SEX section. Love often refers to the relationship between two young men in which they agree they will not snitch on one another. Snitch information is a form of power, since the police and fellow gang-leaders need informants as basic to their authority, “Don’t trust anyone” is the closest they come to a sacred prayer.

Through the eyes of a young policeman, Officer Pete Forcelli, Green reproduces a horrible, but not rare 1988 incident that becomes part of a young criminal’s training. Three armed men barge into a seventh floor apartment and in 30 seconds destroy the nude bodies of three young men enjoying a drug fest. The rug is matted with dirt, blood, razor blades and shards of broken crack vials. Later a policeman turns to his partner and asks, “Why do people live like this?”

Green’s purpose seems more to ask questions like that than to answer them. Most likely these people live in a world— which extends to business and politics— where lies and silence are the main instruments of power. They learn that one lie will require lots more to cover up the fundamental truth. They imprison themselves in an artificial mini-world where long ago love was replaced by fear.

Raymond A. Schroth, S.J., author of nine books, is an editor emeritus of America magazine.