Sneha Dey

The construction crew outside the Lab School in June.

NYC Lab School for Collaborative Studies, a high school in Chelsea, serves 1,056 students. The box-like building is four stories high and the windows and doors are a bright blue. Outside the entrance on West 17th Street, construction takes up half a block. The street doesn’t get a lot of road traffic, but on a sunny day towards the end of the school year, jackhammers and drills were going strong. Outside New York City schools, construction can be active for the entire school day, as regular school hours are within the city’s designated construction hours of 7 a.m.6 p.m., when the city’s Noise Code permits higher noise levels.

At the Lab School, noise levels reached as high as 97.8 decibels the day City Limits visited, enough to cause damage after less than 30 minutes of exposure.

Researchers and citizens are starting to see high noise levels as a public health issue, especially for children. Noise exposure can result in permanent hearing loss, cardiovascular disease, sleep disturbance and tinnitus, according to a recent report by the World Health Organization. Consistent evidence suggests noise exposure also puts children at risk of cognitive impairment. High decibel levels affect central processing and language related tasks, such as reading comprehension, memory and attention. In 2013, a behavioral study investigated the effect of road traffic on 872 children in Germany. The study found children were more likely to be hyperactive if they lived near busy roads.

“Students are a particularly vulnerable group…they are in a critical stage of mental development,” says NYU Center for Urban Science and Progress researcher Charlie Mydlarz.

Measuring school sound

City Limits measured the noise levels near 22 elementary schools across several days during school hours. All schools studied are located in “noisy” neighborhoods, as identified by the New Yorker in 2015. Noise at 85 decibels or higher can cause permanent hearing loss after 8 hours of exposure. Every three dB increase after 85 dB cuts acceptable exposure time in half.

All 22 schools did average noise levels below 85 decibels. But that doesn’t tell the whole story.

For instance, P.S. 234 Tribeca Learning, in Lower Manhattan, averaged noise levels of 83.0 decibels. Noise levels surpassed 85 decibels for 11.3 percent of 15 minutes recorded, the standard time recorded for each site. Unwarranted honking and stationary food-truck jingles produced the biggest spikes in noise. Both sources are illegal in New York City.

At P.S. 132 Juan Pablo Duarte, located at the intersection of Wadsworth Avenue and West 183rd Street in North Washington Heights, City Limits recorded noise levels as high as 104.5 decibels outside the school. A total of five medical centers are within a two-block radii of the school, so sirens are a regular occurrence, along with jackhammers from a construction site in front of the school.

Charter school Success Academy in Hudson Yards is at the intersection of West 41st Street and the major thoroughfare of 10th Avenue. Less than a block away, 10th Avenue crosses the Port Authority Bus Terminal ramp, which runs into Lincoln Tunnel. Honking and truck engines appeared to register the highest readings at this site. While readings at the school average 82.6 dB, they peaked at 100.

Like P.S. 132, Success Academy and PS 234, 18 of the other schools peaked well over 85 decibels. Even P.S. 11 William T. Harris, located in Chelsea, whose noise levels were lowest, peaked above 85 decibels, at 86.3.

Trackdowns can be slow

Currently, dangerous noise levels are supposed to be resolved through the 3-1-1 call system. A resident makes a noise complaint and , the complaint is forwarded to the appropriate agency (either the DEP or NYPD), and later investigated.

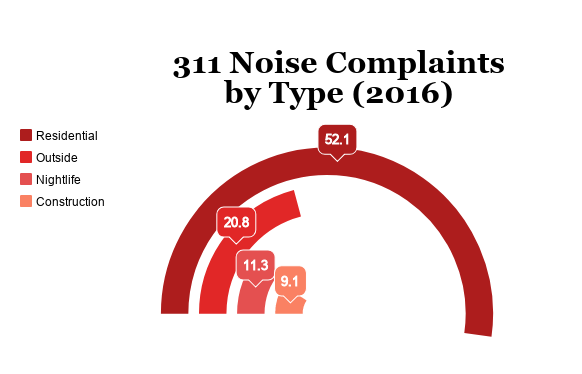

Each year, the number of noise complaints made reaches record highs. In 2016, noise complaints reached an all- time high of 212,318 calls. The number of complaints is growing far faster than city population. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of noise complaints more than doubled. In part, this rise is due to the introduction of the 311 online and text messaging system in 2011, which has resulted in an increase in all 311 complaints.

Complaints pertaining to clubs or bars, businesses, streets and vehicles are routed to the NYPD. All noise violations are considered non-emergencies and so NYPD officers from the local precinct respond when next available. If, upon arriving at the scene, the noise source appears to have stopped, officers need not measure noise levels. In 2016, the New York Post reported a drop in the noise summonses NYPD officers had made.

The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) handles noise complaints involving construction, animals, traffic, air conditioning and ventilation units. The DEP employed 62 noise inspectors in 2018 to investigate noise complaints. Unlike the NYPD, these inspectors always measure the decibel of sound from the source.

The average response time to a noise complaint is four to five days. “Inspections are scheduled when the noise is most likely to happen again. If the complainant states that it happens every Friday night – inspectors will visit on the following Friday night,” a factor which can skew average response time, says DEP spokesman Edward Timbers.

According to a report from the state comptroller, “complaints made through 311 have been ineffective in addressing these specific problems, even in situations where hundreds of complaints have been made concerning the same location.” The comptroller’s office conducted a survey which had 4,116 responses: Of those who reported making a noise complaint, 92 percent also reported the noise was recurring and 83 percent were dissatisfied with how their complaint was handled. Residents who expressed dissatisfaction largely cited a lack of follow up or a feeling the complaint was not taken seriously.

Efforts to document the city’s noise problem are multiplying.

Launched in November 2016, Sounds of New York, a five-year NYU Steinhardt research initiative, uses sensors to analyze and better understand noise pollution. “The research project is still in its initial ‘sensing’ phase and the researchers are installing sensors around the city to capture audio and help train the sensors to recognize different classes of sound. The second phase of the project is concerned with data analysis, where patterns will start to be identified,” wrote SONYC press spokesman Sarah Naomi Binney. The goal of the project is intended to help city agencies resolve the noise problem. Mydlarz along with Justin Salamone are senior researchers for the project.

The group has done a preliminary study, concentrated around the Washington Square area. In this study, they combined and cross-analyzed the log of 311 civic complaints, analysis of SONYC sensor data, and DEP inspector site visit information. What they found supports the comptroller’s conclusion of ineffectiveness. The sensor data found quantitative evidence for 94 percent of all after-hour construction complaints; however, 89 percent of DEP inspection resolutions were “No violation could be observed” and none of the inspections resulted in a violation ticket being issued. This significant gap is likely due to the average response delay in city complaints. Also, if a construction site has obtained an after-hours work permit, a violation cannot be issued, regardless of the noise level.

The state comptroller also reports noise was confirmed in 3 percent of all complaints DEP investigated from 2010 to 2015. “The nature of most instances of excessive noise is that it is either temporary, intermittent or the source may be mobile. These factors contribute to difficulties for an inspector to measure the noise, confirm if it is excessive and then issue a violation,” explains Timbers.

Move (or lack thereof) to protect schools

The complaint’s proximity to a school, or any other facility type, is not considered in the order in which noise complaints are investigated. Instead, noise complaints are investigated in the same order they are received, unless more information about the timing of the noise issue is provided by a complainant.

In the updated noise code, revamped for the first time in 2007, schools, along with hospitals are mentioned once. Under city regulations, when construction activity is planned, a noise mitigation plan must be created. If the construction activity will occur near schools, “the party responsible for construction is expected to design their noise mitigation plan to be sensitive to its neighbors,” according to the Noise Code. “Inspectors take into account the nature of the complainant, specifically if it is a sensitive institution such as a hospital or school, will assess the impact of the noise and work to have the issue resolved,” says Timbers.

A recent piece of local legislation, authored by Councilmember Ben Kallos and passed in January, mandates all noise mitigation plans be filed electronically, effective for all plans created after May 5th. “After years of getting noise complaints then asking the city to do something about it and requesting a copy of the noise mitigation plans, I started to think they didn’t exist. Now we will be able to see for ourselves, force developers to follow the plans, and turn down the volume on construction noise,” wrote Councilman Kallos in an email.

Pending legislation at the local level aims to reduce the effect of transportation noise on schools. In Resolution 294, Councilman Jimmy Van Bramer is asking the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) to install soundproofing systems near schools where subway and train noise reach disruptive decibel levels.

The Peaceful Learning Act appears to be the boldest currently proposed national legislation targeting the impact of urban noise on schools. Re-introduced annually since 2014 by Rep. Joe Crowley (D-Queens), the bill would require a study to be done to understand the effects of nearby noise—particularly trains—on schools. “If you’re a school in the rural area or the farm, I’m not saying there’s no noise but it’s completely different…this will allow for a study of every school to be done and then proper remedies will then be prescribed, in terms of reducing noise in the classroom,” Crowley, who was defeated in the primaries this month, told City Limits. He worked with P.S. 89 Elmhurst in Flushing to create the legislation after the school reported stopping class every few minutes for the above ground train to pass.

3 thoughts on “Unhealthy Levels of Noise Outside Some City Schools”

Noise in NYC is a growing problem. Surely construction — especially construction vehicles — and street repairs contribute to the problem as do narrowing the travel ways on streets with frustrated drivers honking horns. But as a resident of lower Manhattan I think the worst noise offenders are sirens from ambulances, fire trucks and police cars in that order. Something must be done about all of the noise as it definitely increases the stress of living and working in Manhattan, and affects health.

What is not mentioned is the abusive behavior of people with powerful steel systemsnin their cars. In my neighborhood, we are living a nightmare, Vehicles play incredibly loud music at all times of the day and night, Calls to 311 do not help, After many visits to the precinct I and many tenants in my neighborhood were given the cell numbers ofnall the sector officers. That does not help. They rarely answer your text or calls and we probably get less of their involvement. My thoughts on this is that somehow, the city wants to reduce the number of complaints in my area to make it seem as if the problem is not as big. We sit at the bottom of the Mayor’s affordable housing zone in the Bronx. Wherever it is, it needsnto be addressed immediately, it’s a matter great concern for our mental health.

The noise in the city is a serious health problem, not to mention a quality-of-life issue.

Why aren’t the noise laws enforced?

The ridiculous aggressive horn-honking and boom cars, the unnecessarily loud and piercing sirens.