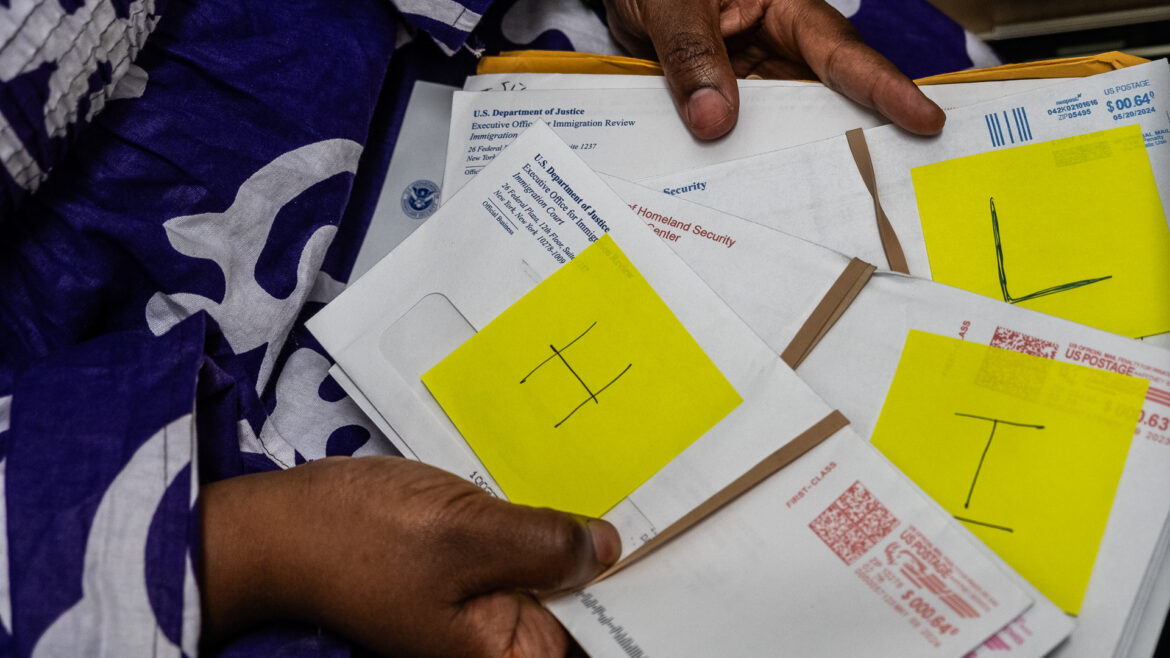

While migrants can receive mail at the city’s shelters, many have struggled to track down important correspondence, according to legal service providers and advocates—especially after the city restricted the length of stays for both adults and families with children.

Adi Talwar

Nonprofit Afrikana in East Harlem provides a mailing address for migrants in shelter and short term housing.In June, when Naykelis and her son had to move out of the Brownsville hotel shelter where they’d been staying for eight months, she was told her mail would be held there for two weeks.

She’d been waiting several weeks already for information about her biometrics appointment to arrive by mail—required as part of her affirmative asylum application, in which she’d provide fingerprints, photographs, and signatures to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

However, after two visits over the next two weeks to the Brownsville site—which she left following a dispute with staff there, transferring to another shelter in Greenwood Heights—she was told there was nothing for her, and that she should change her mailing address as soon as possible.

So she returned to the organization that had helped her apply for asylum, Central American Legal Assistance (CALA), and they called USCIS and confirmed that her appointment information had been sent to the Brownsville shelter.

“I had no trouble with mail before,” said Naykelis, who asked to withhold her last name because she feared harming her immigration case. “The medical card I requested arrived. I received medical bills.”

While migrants can receive mail at the city’s shelters, legal service providers and advocates say many are missing important correspondence, especially after City Hall began restricting the length of their stays.

Families with children are subject to 60-day time limits in shelter, after which they have to reapply for another placement. Adults and couples without kids can remain for either 30 or 60 days, depending on their age, after which they must prove they meet a set of specific criteria to earn more time.

When asked, City Hall did not specify how long migrants’ mail is kept at a shelter after they move out. But both migrants and legal service providers explained that it’s usually held for two weeks after the transfer.

The city says it holds onto what it calls “high-priority mail,” which is basically correspondence from governmental entities (such as court documents, social benefits, or legal correspondence) at its migrant shelters, as well as at the American Red Cross’ New York headquarters, where the city runs its Asylum Application Help Center.

However, organizations that with with newly arrived immigrants—including those that are part of the Asylum Seeker Legal Assistance Network (ASLAN), which provides legal help—have been sounding the alarm about problems with mail in the city’s emergency shelters, more than 200 of which have opened over the last two years as tens of thousands of new immigrants arrived in New York.

UnLocal, which is part of a coalition of immigration legal organizations called the Pro Se Plus Project (PSPP), reported that more than 100 people have knocked on their doors reporting that they don’t get their mail, or don’t know where or how to find it.

Tania Mattos, UnLocal’s interim executive director, said the organization has worked with more than 600 migrants so far this year. “Half of them are in shelters. And then, out of that, about 80 percent of them are impacted by not getting their mail,” she said. “And that’s just us.”

Other organizations that assist with asylum applications and immigration cases that are not part of ASLAN (which receives funding from the city) also reported that many who come seeking help are doing so because they aren’t receiving mail at their shelters.

“People come in and say: ‘Yes, I’ve applied to the immigration authorities, but I haven’t received anything,’” said Jairo Guzman, executive director of the Mexican Coalition. “When we call immigration, they say they sent it. And it’s the resident’s word against the shelter worker.”

In Naykelis’ case, after being told twice at the shelter that they had no mail for her, she decided to go directly to the USCIS Manhattan Application Support Center on June 25 and explain what happened.

“And they accepted me,” Naykelis said with joy. “When I got to the office, they told me that my appointment was for the 20th—I had gone on the 25th—but that my case was still open, so they took my information.”

Adi Talwar

Naykelis, who asked for City Limits to withhold her full name out of fear it could jeopardize her immigration case, missed an important appointment notice after moving out of Brooklyn shelter in June.Delays and deadlines

On July 9, city officials reported that the number of new immigrant arrivals had decreased since President Joe Biden’s executive action barring migrants who cross the southern border illegally from receiving asylum. But there are still currently 64,000 migrants in the city’s shelters, out of the more than 200,000 who have arrived in the last two years.

Most of the organizations City Limits spoke with identified more mail-related problems since the city began changing the rules around length of migrants’ shelter stays earlier this year, and after the legal settlement reached in March that redefined New York’s right-to-shelter policy for adult immigrants without kids, who for the most part are now subject to a 30-day limit.

And a single piece of mail can be essential to being able to move on to the next steps in an immigration proceeding.

An attorney who works with one of the ASLAN member organizations is now fighting the deportation order of a West African migrant who was sent a Notice to Hearing—used by the government to inform those it seeks to deport of an upcoming immigration proceeding— which was mailed to the city’s 30th Street Men’s Intake Shelter in January.

But he never received it. The notice was then returned to the U.S. Postal Service in February, and when the migrant failed to appear in court, the court ordered him removed in absentia in April. The asylum seeker is currently in a detention center in New Jersey.

“In terms of why he was put in detention, I can’t say whether the mail was the reason behind that,” said the non-profit attorney representing the man, who preferred not to be named for fear of prejudicing the case. “But in terms of him definitely being at risk of deportation, and potentially not being able to get asylum relief—yeah, the mail.”

Immigration cases often have time-sensitive deadlines that can be thwarted by lost mail. For example, those who want to apply for affirmative asylum—as opposed to defensive asylum, filed when someone is already facing removal proceedings—must do so within one year after they arrive in the country, a deadline made more difficult to meet by current court backlogs.

Once migrants submit their application, USCIS sends a notice in the physical mail that contains a receipt number—but if it’s not received, this can trigger a domino effect.

“If people are having to move from the shelter within 30 days or 60 days, they obviously are not going to get a receipt notice by the time that they no longer live at that address,” said Lauren Wyatt, managing attorney at Catholic Charities Community Services.

Without the receipt number, Wyatt explained, there’s no way for the person to notify USCIS of a new address. “It’s going to be sent to an address that [they] don’t have anymore,” Wyatt said.

Next steps, such as applying for an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) card, are also dependent on that receipt number, Wyatt emphasized. Asylum seekers can only apply for employment authorization 150 days after they file for asylum, and approval can only be authorized after the clock reaches 180 days. Any delays caused by the applicant will pause that clock, attorneys explained.

“So now I can’t prove to USCIS that I’ve applied for asylum because I don’t have my receipt notice. I can’t let USCIS know that I’ve moved because I don’t have my receipt notice. I can’t get a work permit to support my family, because I can’t prove that I applied for asylum,” she said, reflecting on the possible outcomes. “So it’s a whole mess, is the short answer.”

After the USCIS sends the receipt number, the next step is fingerprints, which are required for both USCIS applications and applications filed with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). “If the person does not get fingerprinted before the final decision of their case, whether it’s with USCIS or with the court, they cannot be granted asylum,” Wyatt added.

To avoid potential issues, many of ASLAN’s member and non-member groups allow asylum seekers to use their organization’s addresses to receive mail. But mix ups still happen.

Hasan Shafiqullah, an immigration attorney with Legal Aid Society, described a recent case where he had to put Legal Aid Society’s address as the mailing address for his client, but the shelter address as the residence, because they had to stipulate where the asylum seeker was actually living.

Shafiqullah thinks his client’s work authorization card was mistakenly mailed to the shelter. “The shelter says they never got it,” he said. “They didn’t know what happened to it; it was like a whole back and forth.”

Shafiqullah had the client come back in to work on a new EAD Card request, and in the process, he decided to pull up the receipt notice on the USCIS website, and found out that the agency was already producing a new card to mail out to his client again.

“It makes me think that the shelter had the card sent back to USCIS because they didn’t know how to find the client because she had been moved to a different shelter back then. And thankfully, USCIS got it because they will only reissue the card if the original one was returned to them,” Shafiqullah explained. “So that was a happy ending for her. Although we never got the social security card, and I imagine that got sent to the shelter.”

Undeliverables, return to sender

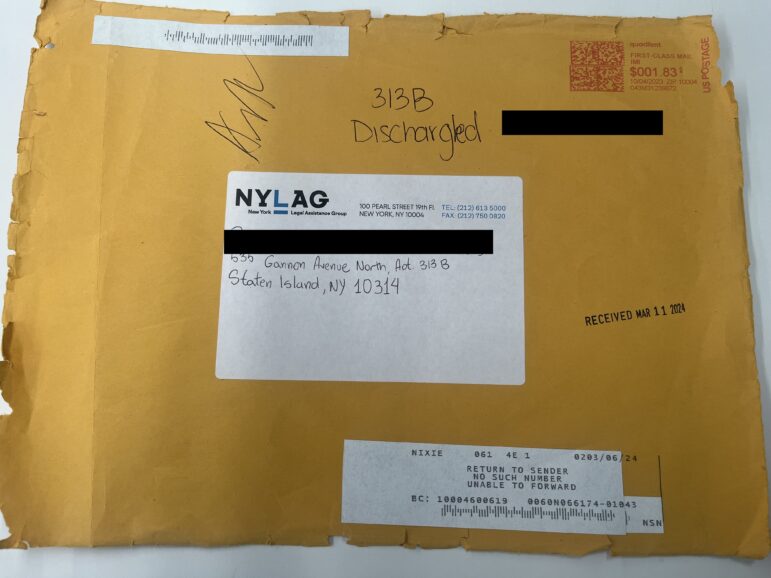

In January, the New York Legal Assistance Group, one of the organizations in the Pro Se Plus Project—which provides assistance in applying for asylum, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and work permits—started to receive the first batch of returned mail.

Whether it is an application to DHS or USCIS, NYLAG sends applicants copies of their documents as proof that the application was filed. However, the copies weren’t delivered.

“We mail them [asylum seekers] this application usually within a week or two after they’re done,” said Allison Cutler, a supervising attorney in NYLAG’s Immigrant Protection Unit, who also runs its Pro Se Plus Project clinics. It was through these returned mailings that they realized that their packages were not reaching people.

Moreover, “we’re seeing that the shelter is actually writing on some of them,” Cutler said. “We have an envelope that actually says ‘discharged.’ And it lists the room number that the resident was in.”

Courtesy NYLAG

A piece of returned mail, initially sent by attorneys at the New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG) to a client staying in a shelter on Staten Island.In that particular instance, just the front of the envelope was returned to the organization. “I’m shocked that [the U.S. Postal Service] processed that return. I have no idea where this asylum application is. I have no idea who opened it. I can only presume it was the shelter. And of course, that’s violating confidentiality,” she added.

The mayor’s office said it does not open mail and, in a limited number of cases, returns mail to the sender when recipients cannot be located for an extended period—although they didn’t specify how many days they hold onto it.

In addition, NYLAG has had trouble sending mail to the city’s massive tent shelter complex at Randall’s Island, saying four envelopes have been returned as “undeliverable.” NYLAG alone has about five people who have not received a copy of their records who they have been unable to contact recently.

“His [the asylum seeker] envelope was actually returned to us as undeliverable because he was a Randall’s Island resident,” Cutler explained. “Thankfully, at that point, we were connected with them [the client] via email, and we were able to mail that individual his copy of his asylum application.”

A City Hall spokesperson said that its HERRCs, such as the one at Randall’s, provide address line guidance to shelter residents, store mail within the facilities themselves, and do not discard or destroy mail, including magazines or spam letters.

The city said it has a centralized database that indicates whether migrants have mail to pick up and alerts them if they have outstanding mail after being transferred to another shelter, but did not elaborate on how the process works.

“Every time a person or family must move out of shelter, they risk losing these essential documents. Missing critical documents can mean missed appointments, court dates, and interviews that severely undermine our efforts to help new arrivals get work authorization and navigate toward safety and stability,” Comptroller Brad Lander told City Limits in an emailed statement.

“As my office found in our investigation of the 60-day rule, the Administration failed to create policies around mail retention and provide families with sufficient information on how to change their address,” Lander added.

Cutler describes that what started as a rarity in January, with a few returned packages a month, has only grown.

“This is affecting people’s work authorization, their ability to obtain safety and stability and economic independence and ultimately, permanent status and protection in the United States,” Cutler noted. “And if they miss an immigration court hearing, they’re risking being ordered deported in their absence. And of course, having their asylum application denied if they had already applied and it was pending.”

Adi Talwar

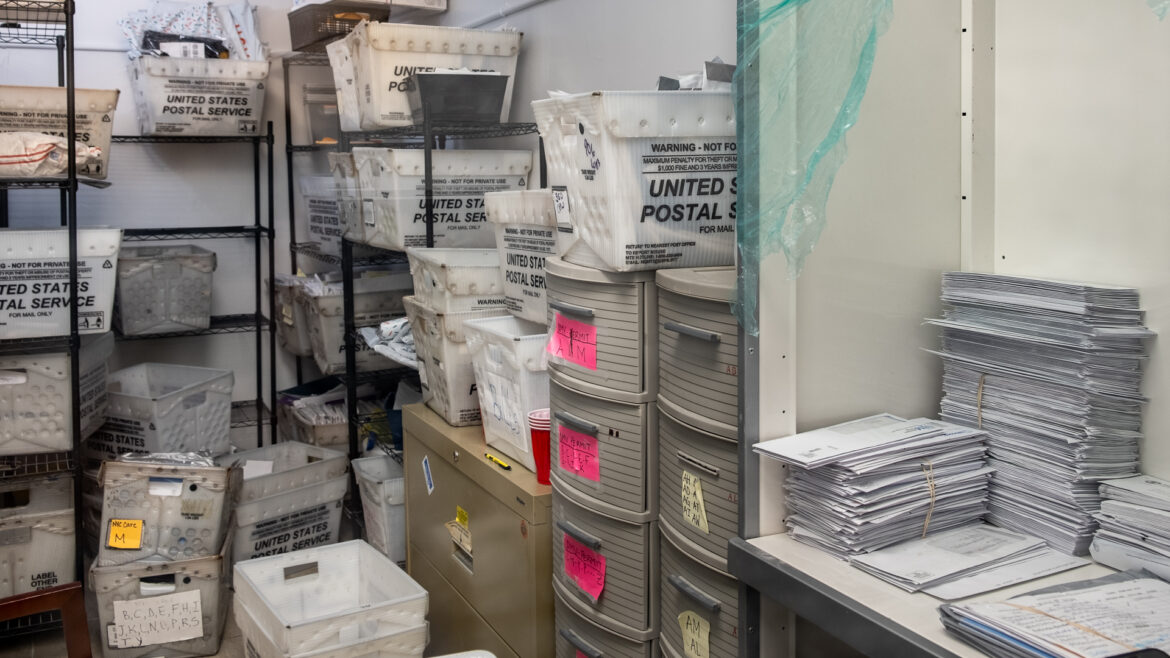

Adama Bah in the mailroom of her Harlem nonprofit Afrikana, which set up the space in 2023 to collect mail for migrants in shelter.‘All types of mail’

Community groups, legal service providers, and volunteers who spoke with City Limits said they have allowed clients to use their organization’s address to receive mail, but only for legal processes. For everything else, like personal letters, migrants and asylum seekers in shelter have limited options.

In August 2023, Afrikana set up space in its Harlem community center to fill this gap, in anticipation of address changes after the city announced it would be limiting the length of people’s shelter stays. What started out as a few boxes for incoming packages quickly grew into a 16-by-9 foot dedicated mailroom, explained Adama Bah, Afrikana’s founder.

“We receive all types of mail,” Bah said, showing a reporter how each column of boxes held specific types of correspondence: personal letters, health care bills, and mail from schools, police departments, border patrol, the DMV (for driver’s licenses), among others. This does not include immigration correspondence, which is kept safely in a locked office inside a locked drawer.

Adi Talwar

Every day, 100 people schedule appointments with Afrikana to pick up their mail. The nonprofit stepped in to help provide a more stable mailing address for migrants in shelter.Afrikana is open Monday through Friday, and every day, 100 people receive mail by appointment, and an asylum seeker who volunteers for the organization is in charge of the mail room. He has a hard copy listing the names of those who have scheduled an appointment to pick up their mail.

Candice Braun, director of programming for Artists Athletes Activists, another organization helping new immigrants, argued that the city should work directly with non-profit organizations like Afrikana to handle mailings for immigrants.

“Just like a mini post office,” Braun said. “They could grant that [money], and there are many nonprofits who would do that.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Daniel@citylimits.flywheelstaging.com. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.flywheelstaging.com

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

One thought on “Missed Mail is Complicating Migrants’ Immigration Cases, Exacerbated by Shelter Deadlines”

This affects not only migrants. Shelters deliver mail late, opened, or never. They transfer people with no prior notice, but don’t forward their mail. Here’s How to Receive Mail Safely.

https://homelessnewyorker.wordpress.com/2022/06/30/how-to-receive-mail-safely/