ANHD white paper

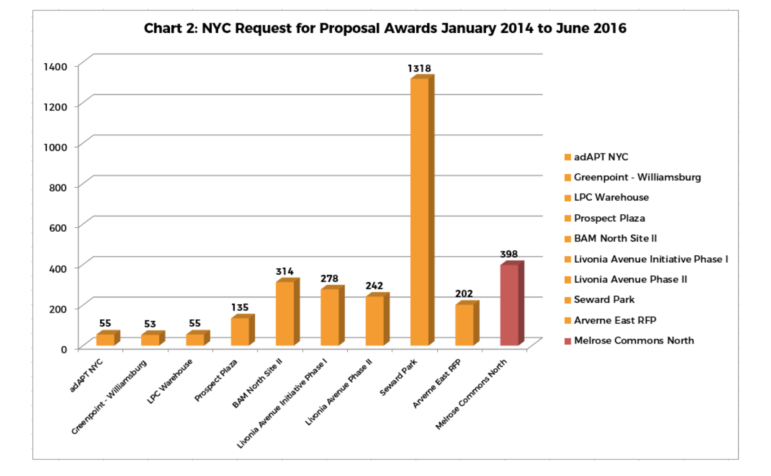

A chart showing that in the first two and a half years of the de Blasio administration, nine of ten development deals for public land went to for-profit developers.

Over the past year, from East Harlem to Crown Heights, we’ve heard residents demand that when the city develops public land, that it partner with non-profit developers. The thinking is this: because they aren’t seeking to pad salaries and often have longstanding connections with the communities they serve, nonprofits are more likely to create more units of low-income housing, be in touch with the needs of the neighborhood, and ensure their buildings remain affordable forever—not just until their subsidy contracts with the city expire.

Nonprofit community development corporations used to dominate the affordable housing sector, but as City Limits reported at length in April, many nonprofit developers say that recent mayoral administrations—including the de Blasio administration—are instead opting to work with for-profit developers. The de Blasio administration has disputed this characterization, but it’s also no secret that the city seeks to find development partners that can deliver the most bang for the buck.

A new report by the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development (ANHD) offers new statistics on the de Blasio administration’s relationship with the nonprofit sector. ANHD, an umbrella organization of non-profit housing and community groups, used data recently made available through Local Law 44, which was approved by City Council in 2012 and requires the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) to make available certain information regarding housing developments that receive city assistance.

Of 193 deals closed during the first two and a half years of de Blasio’s term, ANHD found that for-profit developers dominated new construction deals, receiving 74 percent of those deals, which contained 80 percent of total units. In many of these deals, developers reached out to the administration for financing, but looking just at the cases in which the city actively solicited a developer with a Request for Proposal (RFP) to build on public land, the picture is even more stark: Of 10 projects on city-owned land, nine went to for-profits and only one went to a non-profit. (Although some development teams are a joint partnership between a nonprofit and a for-profit developer, ANHD categorized each joint-venture as either nonprofit or for-profit based on which was benefiting from the mortgage.)

Things were more balanced on the housing preservation side: Nonprofits accounted for 54 percent of deals. However, the 46 percent of deals with for-profits tended to be larger and therefore made up 57 percent of total preserved units. And ANHD notes that giving non-profits lots of preservation deals but shorting them on new construction is not exactly good for the health of the non-profit sector: “New-construction deals allow for significantly higher developer fees than preservation deals and are therefore fundamental to creating developer capacity,” the report says.

So we get it: For-profits are getting a larger slice of the pie—but should it really matter to those tenant and homelessness activists whose top concern is making sure there are more units of extremely low-income housing? The report says it should, at least where new construction is concerned. Among the deals examined by HPD, 84 percent of the units built by for-profits were set aside for households making below $68,720 for a family of three, while the remaining 16 percent of ‘affordable’ units were for families making up to $141,735. In the case of nonprofits, 94 percent of the units went to those families making below $68,720. And the difference between nonprofits and for profits was even starker when looking at deals on public land. (For preservation deals, the income distribution was more evenly balanced.)

One thing worth noting: the report found there is some truth to the notion that you get more bang-for-the-buck working with for-profit developers. Of the deals examined, non-profits received about $64 more subsidy per unit on new construction deals and $15,410 more per unit on preservation deals. The report credits a few different factors, such as that for-profits often get the bigger projects and can cut costs through efficiency of scale, and they include higher-rent units in their development.

Will the de Blasio administration—if the mayor is reelected—engage more with non-profits in a second term? At the least, city agencies do seem to be talking about them more. (Non-profit developers were mentioned twice in HPD’s 2016 East New York housing plan and five times, and with much greater intentionality, in the 2017 East Harlem housing plan.) The city has also begun investing in community land trusts, which by definition are non-profits. But truly prioritizing nonprofits takes first agreeing that they’re worth prioritizing, and—despite rent burden data that shows the need is greatest at the lowest incomes—the administration still frequently contends that the city needs middle-income housing.

One thought on “Study Says Housing Nonprofits Get Short End of Stick Under De Blasio”

Pingback: The Down Low: Classical Concerts In Your Living Room, Empty "Gravesite" In Gowanus & Other Stories You Shouldn’t Miss - BKLYNER