DCP

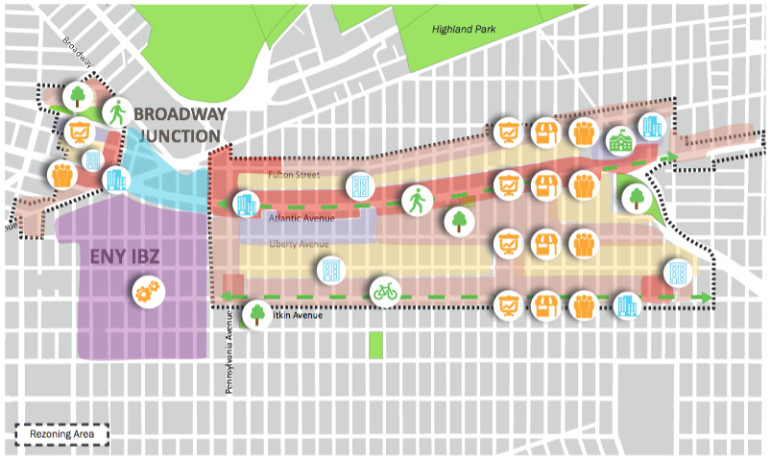

The city’s latest report on East New York designates areas for revised zoning and indicates where new features and programs will be located.

The Department of City Planning (DCP) says that 50 percent of the housing built over the next 15 years in East New York will be affordable to local residents. According to an Environmental Impact Study, developers could build up to 7,000 new units under the new zoning and density rules. Most of those affordable units would be reserved for families making between $23,000 and $47,000* for a household of three. The median household income in East New York is about $32,000.

The 50 percent affordability promise signifies the city’s latest step to gain support for its East New York Community Plan. Last year, Mayor de Blasio designated the long-neglected Brooklyn neighborhood as the city’s first target for affordable housing development and neighborhood revitalization. Yet many residents fear that rezoning to allow higher density is a recipe for gentrification.

The announcement comes on the heels of an alternative proposal released by the Coalition for Community Advancement, an alliance of East New York residents and organizations that began organizing last year to make sure the city’s plan reflected neighborhood interests. City agencies are currently in discussion with the Coalition about the many demands in its proposal.

Several members of the Coalition said they welcomed the news of 50 percent affordability, adding that they would continue to push for more information and protection.

“I think there’s progress. Certainly we’re moving in the right direction,” says Coalition member Michael Keller, director of the North Brooklyn YMCA. “But at the same time, there obviously continue to be some areas that need to be fleshed out.”

City unveils more details

De Blasio hopes to promote affordable residential development in East New York as part of his Housing NY plan to build or preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing over ten years. The plan has been hailed as ambitious and criticized for targeting the majority of housing to families making between $42,000 and $62,000*, although about 43 percent of New York City families make less than $40,000.

At the last East New York meeting in January, the Coalition protested that DCP should offer more specifics, including particulars about the exact number of affordable units, the depth of affordability, and how the neighborhood would absorb new residents without stressing public facilities. Following numerous rallies, DCP postponed the formal rezoning process known as the Uniform Land Use Reform Procedure (ULURP) from May to September. On July 2, at another packed meeting in Cypress Hills hosted by East New York Councilmembers Rafael Espinal and Inez Barron, the city finally offered some concrete details.

Under the city’s plan, about 1,200 units will be built over the next two years, all of them city-subsidized and rented at below market rates. At privately owned sites, the city will require developers to follow the rules of the Extremely Low and Low Income Affordability Program (ELLA), mandating that 10 percent of units be set aside for those earning up to approximately $23,000* for a household of three, 15 percent of units for those earning between $23,000 and $31,000, 15 percent of units for those earning between $31,000 and $39,000, and between 40 percent to 60 percent for those earning between $39,000 and $47,000 (another 20 percent can be for households earning between $47,000 and $70,000). Publicly owned sites will have stricter affordability targets, with more units for the lowest income brackets.

A Biography of East New York

A Brooklyn Historical Society event

Over time, as the East New York real estate market heats up, the city expects developers will be able to afford renting to low-income households without city subsidies. These future projects will be subject to mandatory inclusionary zoning, a policy requiring that all residential development include a portion of affordable units.

DCP also announced that the city has set aside funds to open a new public school in East New York with 1,000 seats. The school will likely be located on Atlantic Avenue and Dinsmore Place, a vacant site that has been tied up in legal battles for decades. Community groups have long said the site would be perfect for a school or a light manufacturing facility.

The city revealed a number of other initiatives relating to improving infrastructure and helping existing residents reap the economic benefits of the neighborhood’s looming transition, including installing a planted median with pedestrian islands on Atlantic Avenue, starting a FastTrac Growth Venture Course for East New York businesses, and launching a study on the East New York Industrial Business Zone to create a plan for a thriving jobs center.

“I think you will find this is a very, very different approach to neighborhood development than the city has undertaken in the past,” DCP Commissioner Carl Weisbrod told the crowd. “It has been an evolving process and as we have learned more from our discussions with you, we have evolved our planning and our thoughts.”

Intense negotiations

East New York’s can thank itself for encouraging this level of detail. The Coalition for Community Advancement’s 10-page alternative plan has advanced a number of demands for the city to consider.

The Coalition’s proposal calls for the creation of a $525 million fund to build 5,000 units of affordable housing over the next fifteen years. If developers build all 7,000 units (the maximum number of units possible, according to the environmental impact statement), this would be equivalent to requiring affordability for 71 percent of units.

The Coalition also wants a parcel of blocks on Liberty Avenue and Atlantic Avenue to remain zoned for manufacturing. The city wants to re-designate these areas “Mixed Use” to allow a mix of industrial, commercial and residential developments, but Coalition members are concerned that owners of industrial land will be tempted to sell out to residential developers, as has happened in other neighborhoods.

The alternative plan also suggests that the city create a fund to help businesses displaced by rising rents, establish a Youth Development Opportunity Center and an East New York-based Workforce 1 Satellite Center to connect residents to job opportunities, require developers to hire locally and pay living wages, and create a “special area-wide zoning district” similar to the Lower Density Growth Management Areas in other boroughs, which would require that developers match residential development to the capacity of community resources.

To oversee these changes, the Coalition has suggested creating an Office of Neighborhood Development to coordinate activity among all agencies, as well as an oversight committee called the Neighborhood Cabinet made of elected members of the community.

In response to the Coalition’s affordability proposal, officials from the Department of Housing and Development (HPD) said they could not agree to a specific number of affordable units.

“We unfortunately have to rely on the market—either nonprofits or private developers—to build,” said Brent Meltzer of HPD. “We need your help,” he added, “to make sure whoever’s building comes to HPD so we can use our programs.” Meltzer didn’t address whether the city has the resources to finance more affordable units or is willing to ask developers for a higher percentage of affordable apartments under the inclusionary zoning program.

The city is also resistant to the Coalition’s manufacturing proposal. Instead, the city hopes to concentrate manufacturing land in the neighborhood’s existing Industrial Business Zone (IBZ). Officials from Small Business Services (SBS) and the Economic Development Corporation (EDC) emphasized their commitment to strengthening the IBZ Zone and providing resources to businesses affected by the rezoning. SBS is discussing establishing a fund to help manufacturing businesses relocate to the IBZ zone, and is strongly considering starting an East New York Workforce 1 Center, in line with the Coalition’s proposal. HPD, EDC, and SBS are discussing expanding requirements for local hiring, but have not yet explored requiring wages higher than those ordered by city law. Developing mechanisms for accountability, such as creating a Neighborhood Cabinet, is something the city hopes to discuss further during the ULURP process.

Not another Williamsburg?

Meanwhile, residents of Jerome Avenue in the Bronx, East Harlem, and other neighborhoods are organizing their own responses to city rezoning proposals.

“In most communities you’re seeing parallel approaches: both engaging with the city and with DCP’s process but also having some form of independent process,” says Emily Goldstein, senior campaign organizer at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. At least on the surface, Goldstein says, the De Blasio administration appears to be more open to community input.

“Communities feel there’s more of an opportunity to engage with the city in new ways but there’s not necessarily trust that whatever the city would on its own come up with would result in what the community actually needs,” she says.

New Yorkers are wary of another Williamsburg-style rezoning—with the city all but ignoring community demands. Before DCP began to pay attention to Williamsburg, the neighborhood had completed its own community-drafted neighborhood plan under section 197-A of the City Charter. The plan called for more affordable, low-density residential development, public waterfront access, and opposition to a power plant facility.

The same year the 197-A plan was approved by City Council, City Planning began pursuing its own rezoning, proposing to turn large swaths of manufacturing land to high-density residential, with the potential for 40-story towers. Neighborhood residents demanded that the city heed their original plan, or at least ensure that 40 percent of units would be made affordable. The city eventually agreed to 33 percent and other compromises. Yet by 2013, Williamsburg had lost more of its manufacturing jobs, and only 13 percent of the total housing rented at affordable rates.

De Blasio’s commitment to 50 percent affordability, his decision to make inclusionary zoning mandatory, and his willingness to set aside funds for a school in advance of the ULURP process does set him apart from his predecessor. But some East New Yorkers remain skeptical that these promises will be enough to prevent displacement, or improve livelihoods in East New York.

Brother Paul Muhammad of the Coalition says the city’s efforts to rezone communities of color—after decades of disinvestment in jobs and schools—is a discriminatory policy worthy of federal investigation, and that East New Yorkers income brackets are not represented by the updated plan. While 35 percent of East New York households make less than $23,000 for a family of three, only 10 percent percent of units at private sites and 15 percent of units at public sites generated over the next two years will be affordable to that income bracket.

“The city is throwing around this word ‘affordable,'” he says, “that has nothing to do with…the poor people here.”

* Income levels at affordable housing projects are typically discussed in terms of Area Median Income, or AMI, a region-wide figure set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development that’s used to determine eligibility for important federal housing tax credits and subsidies. The dollar figures in this article relate to the following percentages of AMI for a household of three:

$23,000 (or $23,310 to be exact) = 30 percent AMI

$31,000 ($31,080) = 40 percent AMI

$39,000 ($38,850) = 50 percent AMI

$47,000 ($46,620) = 60 percent AMI

$62,000 ($62,160) = 80 percent AMI

$70,000 ($69.930) = 90 percent AMI

One thought on “City’s Plan for East New York Tries to Address Gentrification Fears”

Do you have a key for the map you posted?