The city’s trailblazing program guaranteeing legal representation to the city’s poorest tenants facing eviction has been falling short since the state eviction moratorium was lifted last year; many still face housing court alone. State officials told City Limits the program has declined more than 10,000 cases since March 2022.

Adi Talwar

Cathy Barreda, director of the Tenant Rights Coalition at Brooklyn Legal Services in her office located in Brownsville, Brooklyn. “The court thinks that they can decide our caseloads. A lot of longtime practitioners are exhausted,” Barreda said of the current pace of eviction cases.

New York City’s Right to Counsel law was the country’s first to promise representation to the tenants most at risk for eviction: low income New Yorkers. Since it passed five years ago, Right to Counsel has begun to change eviction proceeding outcomes: 84 percent of tenants represented by a lawyer through the initiative stay in their homes, according to city officials.

Though it’s known informally as Right to Counsel, the law is officially called Universal Access to Legal Services. But over the last year, access to the benefit has been far from universal. The number of tenants who have an attorney in the city’s housing court has gone down every month since New York’s eviction moratorium ended in January of 2022, from 66 percent to just 35 percent in the first week of October, according to data tracked by housing advocates. That’s compared to the approximately 95 percent of landlords who are typically represented by lawyers in court.

“There are people who are falling through the cracks,” said Julia McNally, attorney-in-charge at the Legal Aid Society in Queens, one of 18 nonprofit organizations representing Right to Counsel-eligible tenants. “Those people—in the case of an illegal lockout—may never get restored to their apartment.”

More than 100,000 evictions were filed across the five boroughs in 2022, court data shows. That’s a steep drop from the 230,071 filed in 2017, the year that Right to Counsel passed into law, which indicates that it’s been a deterrent to eviction filings. But in every borough, there are more qualified tenants facing eviction than lawyers to counsel them.

“Since March 2022, there have been more than 10,000 cases declined and another 12,000 with limited participation by the Right To Counsel providers,” wrote Lucian Chalfen, director of public information for New York’s Office of Court Administration, via email. In that same time period, the legal service providers accepted about 21,000 cases, according to Chalfen.

Structural issues contributed to the decay of Right to Counsel in 2022, according to more than a dozen attorneys, researchers and advocates who spoke with City Limits. Nonprofit housing lawyers tend to earn lower pay and have a high turnover rate that accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. The courts—facing a backlog of cases—are now putting them on the calendar faster than tenants can get lawyers, and the process of eviction itself is designed to move more quickly than other civil cases.

“I get so many calls every single day, but most of the time, a law student in my class will return the call or I will myself, and we’ll do our best to give the person legal advice,” said McNally. “We’re just so constrained with our capacity that we can’t take walk-ins right now.”

A group of organizations tracking eviction and Right to Counsel data, under a project known as the NYC Eviction Crisis Monitor, reported in October that 12,776 tenants—more than half of all tenants facing eviction who have appeared in court since the moratorium ended—have been denied counsel, either because they did not qualify or because legal service providers were overburdened.

Lucy Block, a researcher at the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD), estimated that more than 80 percent of those tenants likely qualify for free counsel, given the income of those typically facing eviction. To qualify for a lawyer through Right to Counsel, a tenant’s household income must be within 200 percent of the federal poverty line, or $55,500 for a household of four.

Not enough information, not enough lawyers

Right now, many tenants are not aware of Right to Counsel, or how it works.

From 2018-2021, tenants, Right to Counsel providers, government officials and advocates shared knowledge and feedback at a yearly public hearing prescribed by the text of the legislation and hosted by the Office of Civil Justice. Despite the mandate and recent accessibility issues, there was no public hearing in 2022, and according to lawyers and advocates, one has still not been scheduled. A spokesperson for the city’s Department of Social Services (DSS), which oversees Right to Counsel and the Civil Justice office, did not respond to questions about the missed hearing.

“As far as housing, I only know so much,” said Mario, a self-represented Bushwick tenant in eviction proceedings, who asked City Limits to withhold his last name because he fears retaliation from his landlord. “They [judges] tell me things, and I can either agree or say I don’t understand. It was overwhelming.”

Mario says his individual income qualifies him for representation through Right to Counsel, but eligibility is based on household income, and his roommate Travis has returned to work. That prevents both of them from receiving representation, even though they aren’t related. The roommates claim to have called every legal service provider multiple times in search of assistance. They have been told that their case can’t be taken by overloaded attorneys, who have to prioritize other cases.

In a case that City Limits observed in Queens housing court on Oct. 17, landlord and first time homeowner Claudette Gouveia represented herself against a tenant who had a Right to Counsel lawyer. She said that while it’s hard to call the law beneficial as a small landlord without a large cash reserve, it doesn’t have the same impact on big landlords who are “trying to get one tenant out and have 20 more waiting on hand.”

By and large, it’s those big landlords who are most likely to be doing the evicting. Data from the housing nonprofit JustFix shows that 89 percent of all residential rental units in New York City list a corporate owner. City Limits reached out to more than a dozen city-based corporate landlords and their lawyers in an effort to get their perspective on Right to Counsel, but none responded for this story.

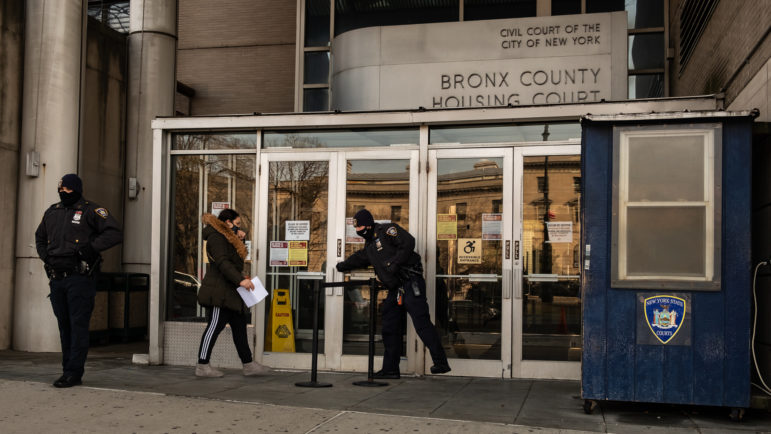

This fall, both Bronx and Brooklyn county courthouses displayed outdated information about Right to Counsel, from before the COVID-19 pandemic, when the program was still being phased in by zip code. During six visits to civil courts in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens, City Limits met tenants who expressed confusion about where to go to get a lawyer, if they qualified for one, and what documentation they needed to provide.

Cases moving too quickly

“We ended up with a supply chain issue,” said Andrew Scherer, the policy director of the Wilf Impact Center for Public Interest Law at New York Law School. He said that attrition is common in housing law, and he’s been working to institute programs that shepherd new lawyers into the field.

But the amount of available attorneys is only part of the problem. Scherer said that while the pace of calendaring and the lack of lawyers are important, a larger problem is the process of eviction itself, and how many people face it. Summary eviction proceedings were originally designed to move more quickly than other types of cases, Scherer explains, an effort to help landlords seize back their property through legal means.

“The courts have not been cooperative enough,” Scherer said. “It’s interesting that they were able to shut it [court] down because of COVID for a long period of time, and then suddenly they opened it up, and it’s as if there’s this incredible sense of urgency that everything has to now keep moving.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, New York City courts created new intake parts, rooms in which qualified tenants can be matched with Right to Counsel lawyers, to speed up the process. But faster matching without more lawyers was one cause of several legal service providers halting intake for periods of time last spring. Managing attorneys at Legal Services NYC, the Legal Aid Society, and The Bronx Defenders—three of the city’s largest Right to Counsel providers—have all said they’ve had to turn down cases due to the pace of calendaring.

“In the Bronx, we’ve been seeing between 110 and 120 cases being calendared a day,” said Runa Rajagopal, managing director of civil action practice at The Bronx Defenders. “A lot of people are showing up, asking for representation, and their cases are moving forward whether or not they have a lawyer.”

Since last spring, legal providers and organizers with the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition have called for the city’s housing courts to slow down the speed of cases so attorneys can better keep up with capacity.

That request is at odds with the perspective of many property owners, who are looking to move eviction cases along after the state’s pandemic moratorium halted the proceedings for nearly two years, and as New York’s COVID Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) has failed to keep up with demand.

“No one has provided owners any deferral or relief from the payment of property taxes or water bills. Insurance and mortgage payments are still due,” the city’s Rent Stabilization Association, which represents some 25,000 landlords, said in testimony to the New York City Council last year about the impact of the eviction moratorium. “There needs to be greater access to the courts.”

In response to questions about the pace of case calendaring, Chalfen of the OCA wrote that: “While we support the idea that as many litigants as possible in eviction proceedings should have attorneys, the Court system is not denying litigants counsel in Housing Court. The inability of the Right To Counsel providers to staff intake calendars is the real reason.” He also referenced “numerous laws and regulations…dictating case movement,” that guide the court’s calendaring speed.

A spokesperson from New York’s Department of Social Services (DSS), which oversees Right to Counsel through its Office of Civil Justice, wrote that it continues to work with legal service providers and the OCA to “ensure that New Yorkers who are entitled to free legal counsel as part of the City’s Right to Counsel program are connected to the supports they need and deserve.”

The city is also working to identify more legal service providers—and thus more lawyers—to add to the program.

Twelve of the initiative’s 18 legal service providers currently list open housing attorney positions on their websites. According to these listings, salaries start at $62,000-$73,000 yearly, which is significantly less than attorneys could make practicing other types of law. Forbes estimates that the average salary for a lawyer in New York state is more than $167,000. And money isn’t the only issue.

“There’s sort of this thing about people not being ‘tough enough,'” said Cathy Barreda, a steering committee member of the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition and the director of the tenant Rights Coalition at Brooklyn Legal Services. She believes that dialogue is harmful, and inaccurate. “I think the morale is just so incredibly low.”

Barreda says even though her union has a cap of 40 active cases, lawyers are often required go above that limit. In addition, the work of nonprofit housing attorneys often expands beyond their court-related duties, and they represent tenants regardless of the merit of their cases. The Right to Counsel program doesn’t pay for paralegals or social workers, which means the lawyers have to spend time submitting ERAP applications and applying for housing vouchers on top of their regular judicial work and what the courts can see.

“The court thinks that they can decide our caseloads,” Barreda added. Despite their best efforts, “a lot of longtime practitioners are exhausted.”

Additional resources could help the program reach more tenants early on, and provide them with that type of assistance in order to avoid eviction proceedings altogether, further freeing up the housing court pipeline.

“There’s a whole host of people who should never be in court,” said Rajagopal. “[They] could get financial assistance, may have matters that should have been resolved, but just end up in the court system.”

In early October, Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine and Bronx Borough President Vanessa Gibson called for a freeze on eviction proceedings when tenants can’t find a lawyer.

Despite the pile up of cases, the council members, alongside the Right to Counsel Coalition, are pushing for the expansion of Right to Counsel to cover people who are above 200 percent of the federal poverty line, but don’t make enough money to hire a lawyer on their own.

“I think it’s rewiring ourselves to see that value on an individual basis, but also from a broader perspective,” said Rajagopal. “We’ve never faced this kind of challenge where we have this hard fought, hard won, beautiful law on the books. It could be more; it could be better, right?”

6 thoughts on “NYC’s Floundering ‘Right to Counsel’ Fails to Keep Pace With Eviction Cases”

Great investigation Annie and Frank! I learned so much

I honestly never reply in the comments, but I felt compelled to here. I agree with the commenter above that this is indeed a rigorous investigatory piece that delves deeply into the issues plaguing RTC with nuance and detail.

However, I cannot get past the framing of the headline and the summary at the top of the article–i.e., the characterization of RTC as “floundering” and “falling short.” As the article makes clear in paragraph one, RTC is exceptionally successful and,–as conveyed roughly half way through–RTC attorneys are working well above their standard case loads to make it work.

It’s not the RTC program itself that is “falling short,” it is the New York State Court system’s unwillingness to create the conditions for it to succeed.

Framing matters immensely, and I think that CityLimits could have done a much better job here. It’s like saying that “recyling is failing” instead of U.S. waste management policies, or that “public schools are failing” instead of focusing on the systems that under-resource them. I honestly expected so much better from this site, and hope you’ll consider a revision that does the article justice.

The courts themselves don’t even have the proper levels of staffing to handle the workload and the staff that’s there doesn’t have the time to get things done.

My case at Queens County New York State Supreme Court with Justice Denis Butler was scheduled and rescheduled several times. I would get an e-mail that a date was set for my case at the court. When I would go to the court house, leaving my house early in the morning to be at the court at 9:30 the room was closed. No notice provided where to go. At the very least the court could have informed me via e-mail informing me that the case has been postposed. Nothing at all. This was so disrespectful of the court. It has scheduled and rescheduled for at least 6 times. When it was cancelled nobody informed me. Shameless court of Judge Butler.

My case at Queens County New York State Supreme Court with Justice Denis Butler was scheduled and rescheduled several times. I would get an e-mail that a date was set for my case at the court. When I would go to the court house, leaving my house early in the morning to be at the court at 9:30 the room was closed. No notice provided where to go. At the very least the court could have informed me via e-mail informing me that the case has been postposed. Nothing at all. This was so disrespectful of the court. Shameless court of Judge Butler.

The article highlights the challenges New York City’s Right to Counsel program is facing in keeping up with the volume of eviction cases post-moratorium. As a lawyer, I can certainly appreciate the strain on legal aid services due to high caseloads and limited resources. The lack of awareness about the program among tenants, combined with the fast pace of court proceedings, further exacerbates the situation. It’s clear that while the Right to Counsel law has had a positive impact in deterring eviction filings, its effectiveness is hampered by systemic issues. This could be a valuable lesson for other jurisdictions considering similar legislation. It’s crucial to ensure adequate funding and resources for legal aid services, as well as to implement measures to slow down the pace of eviction cases to allow for proper representation. Additionally, increasing public awareness about the program is vital to ensure eligible tenants can access their right to counsel.