An annual vigil honored the New Yorkers who died on the streets and in shelters while highlighting the lethal impact of chronic homelessness. “We should be clear that these outcomes are the result of public policy choices we make in the United States,” said one of the organizers.

Adi Talwar

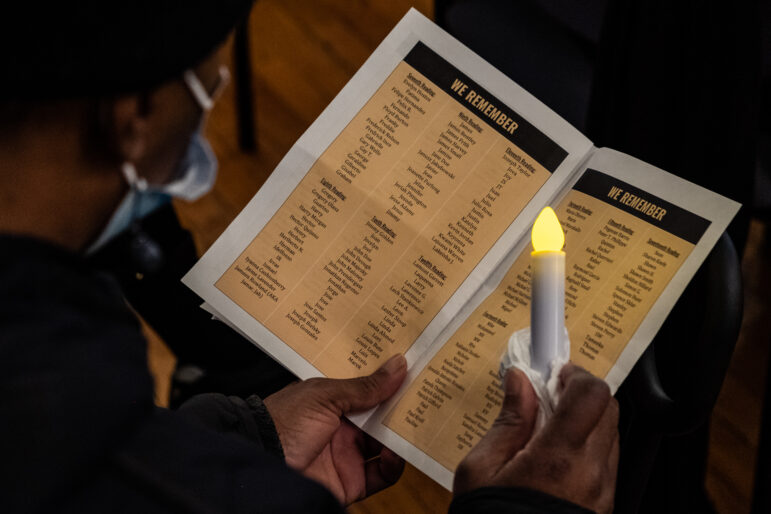

As a part of the memorial, names of those who passed this year were read out accompanied by a tolling bell at the 2022 Homeless persons’ Memorial Day event at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in Manhattan.For six months, Judy Romer lived on the ground, huddling in Herald Square while forming a bond with two other women who slept beside her. But over the past year, both women died, Romer said. So did four other close friends who were also experiencing homelessness.

On Thursday night, Romer remembered her friends Cassidy and Carol, along with “Jose the Dancer,” Arthur and “Scotty from the Upper West Side,” during an annual Homeless Persons Memorial Day vigil inside a Midtown church, adding their names to a list of at least 300 homeless New Yorkers who died this year.

“We’re falling through the cracks,” said Romer, who now stays in a Lower Manhattan shelter. She said she became homeless after she was evicted following her husband’s death. “It’s devastating.”

The December observance is organized each year by the service providers Care For the Homeless and Urban Pathways, whose staff compile names and as much information as possible about people who died in the streets and subways, in shelters, or, at times, shortly after securing permanent housing. Their goal is to honor the lives lost and to shine a light on the systemic inequities and austerity policies that deprive people of stable housing while fostering illness and death.

Adi Talwar

Judy Romer said she lost six of her homeless friends during 2022. “We’re falling through the cracks.”

Put simply, homelessness kills, said Care For the Homeless President and CEO George Nashak.

“In this, the richest society on Earth, we tolerate devastating health disparities based on the color of a person’s skin with the amount of money they have in their bank account,” Nashak said. “We should be clear that these outcomes are the result of public policy choices we make in the United States.”

Indeed, poverty and lack of stable housing lead to a greater incidence of chronic illness, lower rates of preventive health treatment and decreased life expectancy compared to the general population, studies show. People experiencing homelessness are also at a greater risk of violence and have limited access to consistent mental health and substance use treatment.

“We must reject the idea that the deaths of people experiencing homelessness are, in some way, an inevitable or acceptable consequence of their circumstances or their personal realities,” Nashak said.

The 2021 fiscal year was the deadliest on record for New Yorkers experiencing homelessness, according to an annual report issued by the city’s health and homeless services departments. That bleak trajectory appeared to continue through 2022—punctuated by the high-profile murder of a man sleeping in a doorway as well as under-the-radar deaths of unidentified New Yorkers.

As the city’s shelter population reached record highs, and thousands of people continued to seek refuge in the streets and subways, chronic illness, fatal accidents, substance use and violence continued to take their toll.

As a part of the memorial, names of homeless people who passed during 2022 were read out accompanied by a tolling bell.

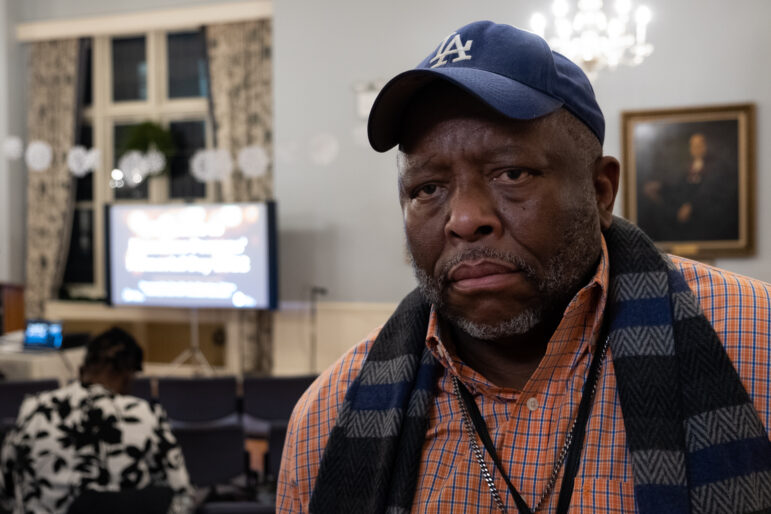

Robert Robinson attended the vigil. He experienced homelessness after he was laid off from his job and spent 10 months in shelter. He is now a professor at The New School.

The event was hosted by Urban Pathways and Care for the Homeless

“The last few years I think we’ve lost more people than I’ve ever experienced in my career,” said Urban Pathways Deputy Executive Director Lisa Lombardi. “Every day you’re saying, what’s next? And you’re also asking…’What did we do wrong?’ We didn’t do anything wrong [but] you feel so responsible.”

From a podium, Lombardi eulogized Lavone G., a vibrant advocate for herself and her peers at an Urban Pathways shelter who fulfilled her goal of landing a job and who “never hesitated to tell us what we could do better.”

Attendees held candles and a bell chimed as provider staff, volunteers and people experiencing homelessness read from the long list of names—from A.G. to Zolan M.

The vigil recognized military veteran and 9/11 first responder David Lopez as well as Felix Rivera, a shelter resident who greeted everyone with a warm smile and had a knack for winning raffles and contests.

Charisma White remembered her son Kwami White, who died in July, just shy of his 30th birthday. Her son, she said, “extended his love, kindness and sense of family with all who he came in contact with, especially those in his LGBTQ community.”

“Kwami was never scared to believe who he was, and knew he had all the love of his mother to be himself,” she continued. “He never failed to let people know that there was something to live for.”

Others died without identification, their bodies buried in anonymous graves on Hart Island.

Scott McDonald, a consumer advocate with Urban Pathways, said the vigil served to recognize them with the reading of Jane Doe and John Doe.

“Homelessness and poverty needlessly robbed these brothers and sisters of their health, their dignity, their lives and even their names,” McDonald said. “We know these individuals have a life of value, a life filled with stories and of wisdom that can no longer be shared with our community.”