The new regulation could have a “chilling effect” on advocacy by residents who use photos and videos to show proof of problems inside New York City homeless shelters.

Adi Talwar

A shelter in Brooklyn.

A new rule banning photos and video inside New York City homeless shelters could prevent residents from documenting dangerous conditions and fuel unnecessary run-ins with security, warn clients and advocates now urging the city to change the broad regulation.

The Department of Homeless Services (DHS) rule, which took effect Nov. 1, prohibits tenants and staff from taking pictures, recording video or livestreaming inside shelter common areas to “protect a client’s right to privacy”—a concern among residents and staff who say they do not want their faces or identifying information posted online. Residents who violate the rule are subject to “suspension of services,” meaning they could be kicked out.

But the regulation has left residents and their advocates confused and concerned, saying the ban could remove a layer of oversight at a time when the shelter system is struggling to meet capacity. They worry clients could be punished for documenting problems—or even video-chatting with friends and family.

“My roommate FaceTimes with her friends. Is she going to get in trouble for that?” said Wykeshia Mitchell, who shares a room with several other women in a shelter in The Bronx.

The agency said the new rule does not prohibit recordings or photos that show shelter conditions as long as client faces are not shown. But DHS has not spelled out any of that nuance in the “No Recording” posters now stuck to shelter walls.

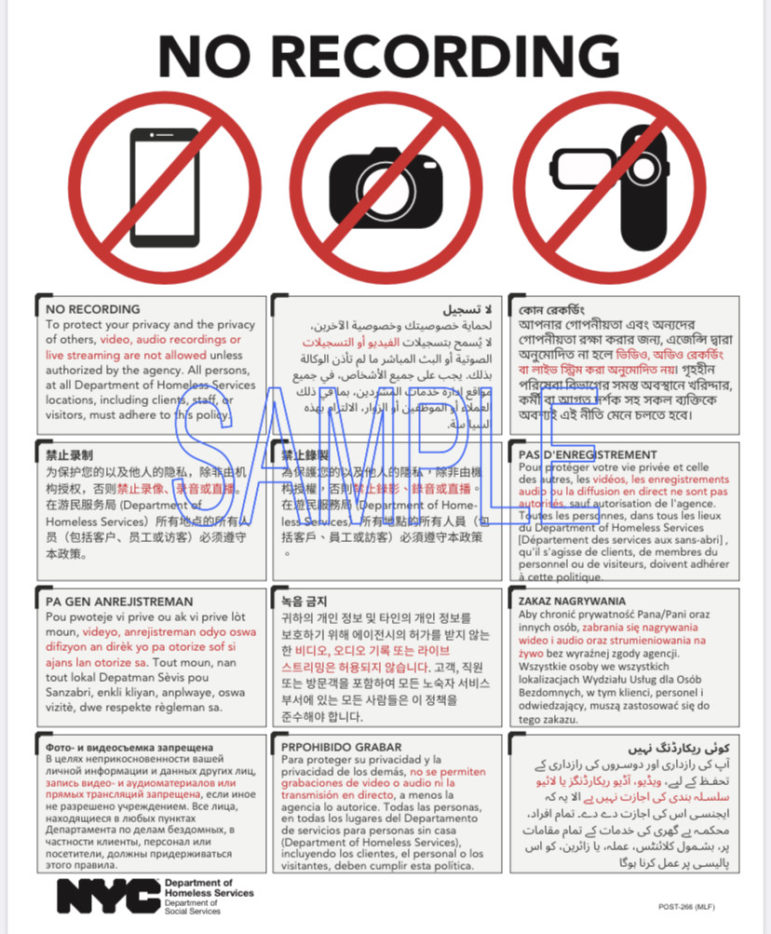

DHS

A poster in DHS shelters instructing residents not to record.Mitchell said her shelter has such a poster, attached to the rule issued by DHS, which features images of crossed out cell phones and cameras, along with a message informing clients and staff that “Video, audio recordings or live streaming are not allowed unless authorized by the agency.”

“Most people in shelters don’t see these policies but they do see these flyers,” said Coalition for the Homeless Policy Director Jacquelyn Simone. “It creates more confusion and unnecessary tension.”

A DHS spokesperson told City Limits that the new rule is meant to preserve client privacy, especially for minor children.

“All DHS clients have a right to privacy when receiving DHS services, and it is our duty as an agency to provide services that maximize client privacy while ensuring their health and safety,” the spokesperson said, adding that DHS has not discharged any clients from shelters this year for violating the rule.

But recordings play a part in shelter oversight by offering proof of problems, according to residents and advocates. Simone said clients frequently share photographs and video with the Coalition for the Homeless, which has the court-appointed authority to inspect shelters and report issues. She listed a few examples, like lines of people waiting for broken elevators or crumbling walls and fixtures inside shelter bathrooms. Other clients use their social media to document what life is actually like inside shelters, opening a window for the broader public.

The rule could have a “chilling effect on that type of self advocacy,” she said.

“I hope DHS strikes a better balance between protecting clients’ privacy and allowing people to document their experiences and conditions in the shelter,” she added.

The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) also said protecting the identities of shelter residents is important, but called the regulation “overly broad.”

“It risks suppressing documentation of conditions in city shelters, including cases of violence,” NYCLU said.

Photos and video taken by clients have exposed serious problems and fueled changes to the shelter system. In September, a shelter resident filmed a DHS police officer assaulting a 21-year-old man who had recently arrived in New York City from Venezuela. The video led to a suspension for the officer and scrutiny of staff treatment of asylum-seekers and other recently arrived immigrants in the shelter system.

Residents have previously used cameras to document egregious problems inside shelters—like roach infestations, spoiled food and violence that led to the 2014 closure of the notorious Auburn Family Residence in Fort Greene.

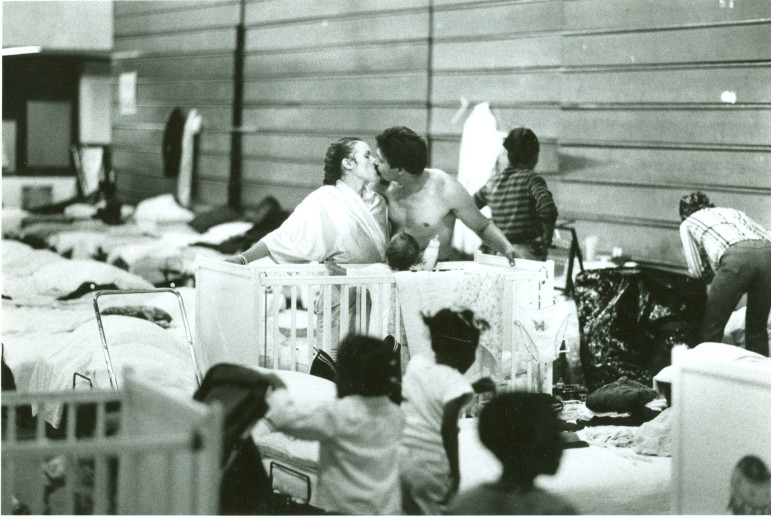

Photos have also played an important role in shaping public sentiment. Pictures showing rows of beds and cribs inside barracks-style shelters of the 1980s and 1990s informed new regulations mandating that families stay in individual rooms. Pictures revealing the state of the city’s intake offices, where families frequently spent days on end sleeping on floors and chairs before getting a shelter placement, helped drive new rules.

George Cohen/City Limits’ Archive

Sensa Alomar and Elias Rodriguez at a homeless shelter in the Highbridge neighborhood in the Bronx in June 1985.

“There will be no accountability because reporters would never know what’s going on,” said Alphonso Syville, who spent 11 years in shelters after he was evicted from the Brooklyn apartment he was subleasing.

Syville, who now lives in a Harlem apartment, said the rule could be used to punish people who share photographs with journalists or with the Coalition for the Homeless.

He said he would understand a rule that prohibits filming clients’ faces without permission, but thinks residents should be able to tape conditions or staff encounters to create a record in case of violence or conflicting reports.

“Staff put their hands on clients. My whole thing is safety,” he said, adding that he used his phone to document ceiling holes, burnt walls, feces on floors and spoiled food during his time at the large Fort Washington shelter in Northern Manhattan and the notorious HELP-Meyer shelter on Wards Island. In September of 2021, a man was trapped in an elevator with no food and little water at HELP-Meyer for four days—one of many problems documented at the facility in recent years.

For Ron Brynaert, a journalist living in a shelter in The Bronx, the rule should be spelled out so that it does not lead to unnecessary and potentially dangerous confrontations—a security guard taking a phone away from a client, for example.

“I think there is a concern that people could go in there and maliciously post footage on the web,” Brynaert said. “But they should make a specific rule.”

He said the broad rule poses a “very good freedom of speech issue” because it could impede crucial citizen journalism.

“Just deal with problems individually,” Brynaert said. “They can’t stop you from taking videos if you really have to.”

2 thoughts on “‘No Recording’ Policy in City Shelters Draws Backlash From Residents and Advocates”

Shelters are the best rac-ket in town. DeBlasio was giving his wife 240 million/year. to run her shelter company.

Nobody saw anything wrong with this. This outrage was a sheer conflict of interest. They use privacy as an excuse to violate the residents civil rights.

LIVING IN A SHELTER AT 94 MASTIC BLVD AND THEY HAVE CAMERAS ALL THROUGHOUT THE SHELTER, VIOLATING RESIDENTS RIGHT TO PRIVACY ESPECIALLY DUE TO THE MICROPHONE ON.