A bill introduced in the City Council this week would create a 15-member commission that includes people who have experienced homelessness to study current shelter locations, identify new sites and figure out how to pay for them. “Homeless New Yorkers come from every neighborhood in New York City and accordingly we need to equitably site shelters,” the bill’s sponsor said.

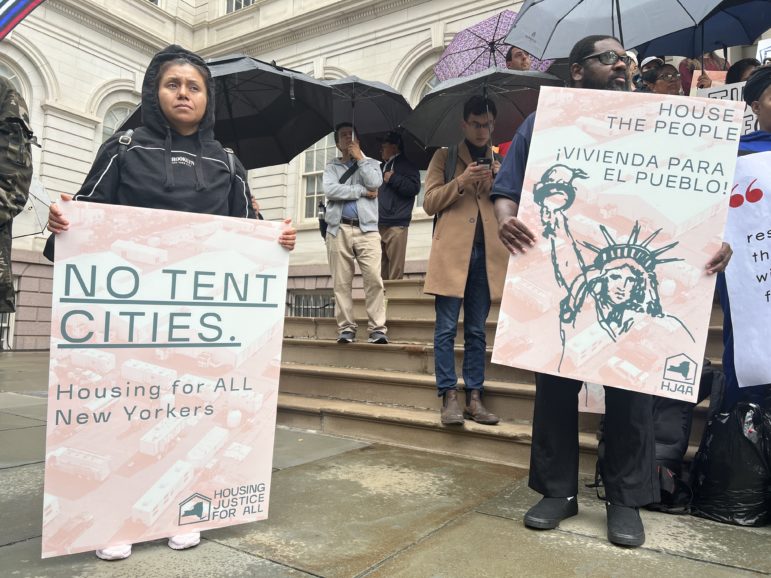

Courtesy Housing Justice for All

Lawmakers and advocates rallied Wednesday outside City Hall, calling for the city the fast track affordable housing placements for people in shelter.

This story was produced with reporting by student journalists in the City Limits Accountability Reporting Initiative For Youth (CLARIFY).

The number of people staying in Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters reached an all-time high Monday, further straining capacity in the network of facilities that serve New Yorkers most in need and spurring calls for comprehensive solutions.

All told, 64,077 individuals stayed in a shelter administered by DHS on Oct. 10, data tracked daily by City Limits shows. That’s up from 46,591 on Jan. 2, before a growing number of recently arrived immigrants made their way to New York City from the southern border as statewide eviction protections ended and average rents continued to skyrocket.

In new legislation introduced before the City Council Wednesday, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams proposed taking a more comprehensive approach to shelter siting to meet the city’s needs while ensuring space is available to New Yorkers near their social networks and familiar neighborhoods. The proposal bears similarities to a 2017 plan to address homelessness introduced by the Mayor Bill de Blasio, but with more regimented community engagement measures.

The bill, cosponsored by Councilmember Lincoln Restler, a former advisor to de Blasio on shelter siting issues, would create a 15-member commission that includes people who have experienced homelessness to study current shelter locations, identify new sites and figure out how to pay for them.

“Housing and homelessness are citywide crises, and meeting them requires citywide solutions,” Williams said in a statement ahead of the Council meeting. The process would engage communities to locate suitable locations, said Restler, who also co-sponsored another bill with Williams to improve safety inside shelters.

“Homeless New Yorkers come from every neighborhood in New York City and accordingly we need to equitably site shelters, improve safety in shelters, and double down on our commitments to end homelessness,” he said.

DHS did not provide a response to a request for comment on the bill Wednesday. In August, the agency told City Limits that there were 59 planned shelters in development, with local communities having received notification. This story will be updated with any additional response.

The commission proposed by Williams would take a longer view of the city’s homeless shelter needs, hold regular public meetings and issue periodic reports. In the meantime, the current crisis demands immediate action to move residents into permanent homes and free up space for newly homeless New Yorkers, advocates say.

In a joint statement Wednesday, the Legal Aid Society and Coalition for the Homeless—court appointed monitors of the DHS shelter system stemming from a landmark court decision establishing the right to shelter—urged the city to create and open up “affordable housing for the New Yorkers who need it most.”

“The increase in the shelter census is fueled by rising numbers of people entering the system, by bureaucratic bottlenecks precluding residents from transitioning into permanent and safe affordable housing quickly,” the two organizations said.

In a plan citing several stories by City Limits, the City Council proposed a number of strategies to help people move from shelters to apartments quickly, mainly by issuing housing vouchers more quickly and easing complicated administrative hurdles.

“It is also imperative to now fix long-standing issues in our approach to homeless services that keep people in temporary shelters longer than necessary and make us overly reliant on the shelter system,” said Council Speaker Adrienne Adams. “Inefficient policies and bureaucracy slow access to rental housing vouchers and supportive housing placements, which we need to focus on fixing to move people into available permanent housing.”

Mayor Eric Adams said in a speech Friday that he would soon unveil a plan to streamline moves out of homeless shelters, where the average length of stay for families has increased and the number of people moving out with rental assistance vouchers has lagged. The rate of moves from shelters to vacant NYCHA apartments has also decreased in recent years, at the same time as thousands of survivors of domestic violence are forced to leave a specialized shelter network and enter the strained DHS system each year.

Absent immediate housing solutions, the city has been forced to set-up additional shelter beds in a hurry.

DHS has scrambled to lease space for families and individuals in more than 45 hotels across the city, though the number of vacant and available rooms is dwindling, Adams said Tuesday. His administration has also contracted with a private company to set up a refugee camp-style tent city for asylum-seekers in a Randall’s Island parking lot, negotiated with a cruise line to house people in spare boats and issued an executive order to streamline the opening of additional emergency sites. On Thursday, he ruled out turning the Javits Center into an emergency shelter.

He has also repeatedly called on elected officials and communities to accept new shelters.

“Everyone must be in the game,” he said in July. “You cannot say, ‘Let’s house our homeless, let’s get them off the street, but just don’t put them on my street.’ You can’t do that.”

On Wednesday, Adams announced the latest plan to house 200 immigrant families at the Row Hotel in Midtown Manhattan, though the shelter will not be overseen by DHS and could avoid the oversight required of the broader system under court order.

NIMBYism, or Oversaturation?

The ad hoc strategies for securing new space come five years after former Mayor Bill de Blasio issued a plan, entitled Turning the Tide, to close commercial hotels and privately-owned apartments used as temporary shelters, while also creating higher-quality, “purpose-built” shelters in every community district in the city.

While he succeeded in getting out of hotels and the notorious apartments, known as cluster sites, the shelter parity proposal encountered extreme opposition from residents in many corners of the five boroughs who refused to accept homeless neighbors. Many of the planned shelters were never built.

That left New York City—which has a unique right-to-shelter guaranteeing a bed, at least temporarily, to anyone who visits an intake site—with fewer facilities to meet the urgent need that has arisen in 2022, following a decade-long low in the shelter census.

Adams did the city few favors in the early days of his tenure when top officials killed or modified additional shelters in the pipeline, often for political reasons, according to several DHS officials who have spoken to City Limits.

“You can’t slow this down, because every day you don’t bring on the capacity, the problem worsens,” said one staff member who asked to remain anonymous so as not to be fired.

The agency and City Hall have disputed the notion that shelters were killed for political reasons.

Nevertheless, the decisions to halt or change shelters hindered capacity at a time when experts predicted the population would rise, as a statewide eviction freeze ended, rents soared and low-cost apartments grew harder and harder to come by. But the problem has gotten exponentially worse with the unexpected increase in newly arrived immigrants in need.

“The city must create a pipeline of new shelter capacity that we can trust so we can plan for future surges and stand up the kinds of facilities with thoughtful design and proper planning our clients deserve,” Homeless Services United Executive Director Catherine Trapani, who represents shelter providers, testified at a July Council hearing.

The uneven distribution of existing shelter beds has fueled tension between communities with multiple shelters—disproportionately lower income neighborhoods where shelter residents previously lived—and those with few to none. As of July, eight of the city’s 59 community districts had no buildings being used for shelter, while others had more than a dozen. DHS said shelters are in the works for every community district, though they have begun to count shelter distribution by Council District instead.

A map of NYC DHS shelter lo… by Jeanmarie Evelly

“We have no say,” Viola Greene-Walker, district manager at Brooklyn’s Community Board 16, told City Limits in an interview this summer. The district, in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, had 22 shelter sites in use as of July, including five in commercial hotels, more than any other part of the city. More than a third of residents in Brooklyn CB16 are below the poverty line and 69 percent are Black, according to 2020 census data.

Some wealthier, whiter neighborhoods host far fewer shelter beds, the July data shows: Manhattan CB4, in Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen, had only four. Manhattan districts CB1 (the Financial District and Tribeca) and CB8 (Upper-East Side and Roosevelt Island) have just one shelter each. Manhattan CB2, in Greenwich Village and Soho, has zero. The community boards for these districts did not respond to City Limits’ request for comment for this story.

“Other areas should help take the burden of housing the homeless,” Greene-Walker said.

That was the philosophy behind the “Fair Share” policy added to the City Charter in 1989, which aimed to “foster an equal distribution of public facilities throughout the city.” However, the policy “has not worked as the Charter Commission intended,” according to a 2017 report by the New York City Council. “In many instances, the City’s facilities and services are not more evenly distributed—in fact, their distribution has become less fair since 1989,” the report said.

De Blasio’s 2017 Turning the Tide Plan described a goal of setting up at least one shelter in every community district—because homeless New Yorkers come from every single district—but also explicitly outlined the goal of “keeping homeless people as close as possible to their own neighborhoods,” typically lower-income parts of the city. But that has left many advocates and directly impacted New Yorkers unsettled.

“When we talk about fair share, why do you concentrate shelters in places like Brownsville, like the South Bronx, different areas of the Bronx, like Harlem? You concentrate them because there is less push back,” said Shams DaBaron, an advocate known as Da Homeless Hero on social media.

DaBaron previously lived in shelter based at the Lucerne Hotel on the Upper West Side, where the city placed around 300 homeless men in the summer of 2020—an effort to clear crowded congregate shelters during the height of the pandemic. Neighbors who opposed the move protested with rallies and a lawsuit, prompting de Blasio to evict them from the hotel.

Sara Newman, director of organizing at Open Heart Initiative, a community group formed in response to the Lucerne controversy that creates welcoming spaces for the homeless, echoed calls by other advocates for alternatives to shelter, namely in the form of more affordable housing.

“There’s no reason that it should take so long,” for shelter residents to secure permanent homes, she said. “In an ideal world, what you would see is that housing would truly be a human right.”