Adi Talwar

A four-month City Limits investigation looked at all aspects of the city's solid waste management system and found steep challenges at every turn. While Mayor de Blasio's OneNYC proposals identify many of these same issues, his ideas also open up many questions.

This story is the first in a five-part series

on waste in the city.

* * * *

Garbage is one of the only things that unites all New Yorkers. Everyone creates it—yet few people want to think about what happens next.

Since the Fresh Kills landfill closed on Staten Island in 2001, New York has shipped every single ton of refuse outside its borders to be buried or burned. The complicated process behind this has inspired debate among city officials, environmental activists, academics, business owners and local residents for years. Almost everyone agrees that the current system has become environmentally and financially unsustainable.

On April 22, Earth Day, Mayor Bill de Blasio vowed to change it.

“The whole notion of a society based on constantly increasing waste and then putting it into a truck or a barge or a train and sending it somewhere else – you dig a big hole in the ground, you put the waste in the ground – that is outrageous and is outdated and we’re not going to be party to it,” he said at a press conference in Hunts Point, one of the city’s waste transfer station hubs.

The mayor pledged to send zero waste to landfills by 2030, a 90 percent reduction based on 2005 levels. This ambitious goal will require one of the most significant shifts in garbage policy that New York has ever seen.

A four-month City Limits investigation looked at all aspects of the city’s solid waste management system and found steep challenges at every turn. While de Blasio’s OneNYC proposals identify many of these same issues, his ideas also open up many questions.

How will New York City send zero waste to landfills without expanding the controversial use of incineration? How can the city ensure the separate stream of commercial waste is handled in a way that protects the environment and workers? How can equity be maintained among the neighborhoods that host different parts of the disposal infrastructure? And perhaps most importantly, how can producer and consumer behavior be changed to create less waste in the first place?

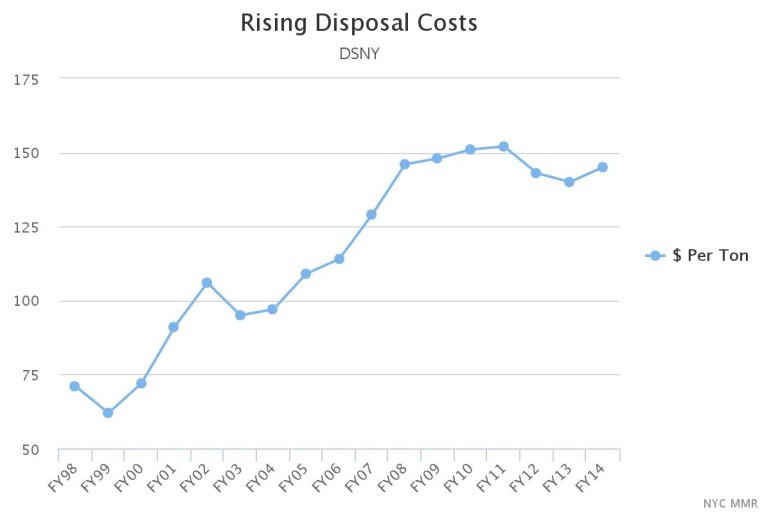

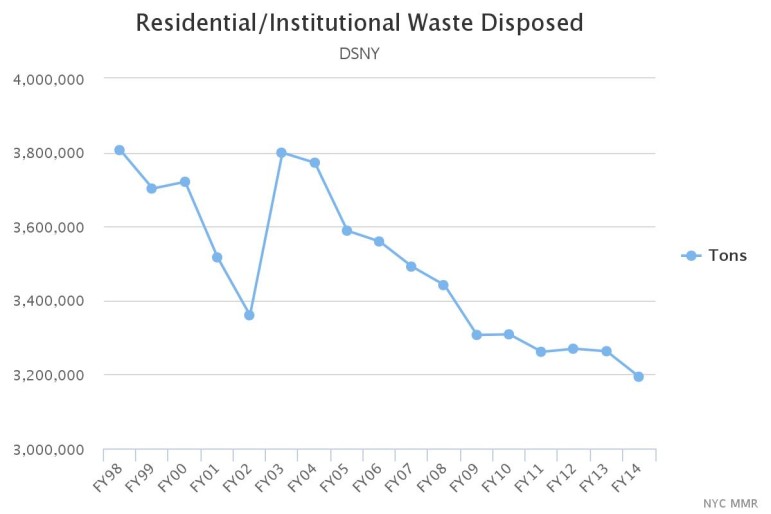

Waste—a leading NYC export

The Department of Sanitation (DSNY) collects more than 3 million tons of residential and institutional waste per year. Approximately 16 percent of that is diverted for recycling. About 12 percent is sent to a waste-to-energy facility in Newark, New Jersey. The remainder travels hundreds of miles to landfills in multiple states. This exporting process will cost the city an estimated $367,815,000 in Fiscal Year 2016. Even though the overall amount of waste produced by the city has slightly decreased since the closure of Fresh Kills, disposal costs have more than doubled due to the expense of exporting.

Estimates of commercial waste, collected from private businesses by private carting companies, range from 3 million to 5.5 million tons a year. This doesn’t include construction and demolition debris. Because DSNY doesn’t control commercial waste, estimates of recycling diversion rates vary widely. The commercial waste that isn’t recycled also goes to landfills, though some is incinerated.

In 2014, residential and commercial waste traveled to landfills as far as 660 miles away in South Carolina, Kentucky, Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania and upstate New York. Many other cities also use landfills, but New York’s waste travels farther than most at an accelerating cost with an equally harmful impact on the natural environment.

“The single worst thing we could possibly do with garbage is landfill,” says Brendan Sexton, a former DSNY commissioner and current member of the Manhattan Solid Waste Advisory Board.

Sexton says that even with the latest landfill technology, water contamination and methane emissions are still an issue. Some of this methane is captured for reuse, but it’s estimated that New York’s waste is responsible for nearly 2.2 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year.

Even if recycling rates spiked overnight, reliance on landfills would still be hard to kick. The city is engaged in long-term contracts with waste-hauling and landfill companies for hundreds of millions of dollars. A representative from one of the country’s largest industry trade associations says his members don’t endorse change until a better option is available.

“People are looking every day at how to build that silver bullet. The day it is found, it’s going to spread like wildfire,” says Steven Changaris, Northeast regional manager of the National Waste & Recycling Association. He says his members are aware there is progress to be made, but also asked for more understanding. “I really want people to take the long view,” he says. “We used to take waste and just dump it in the ocean. We used to take waste and just put it in a hole in the ground.”

In New York’s case, this is especially true. Deadly cholera and yellow fever outbreaks, due in part to unsanitary street conditions, were common until the mid-1800s. The city didn’t stop dumping its waste in the ocean until a direct court order in 1934. New Jersey and surrounding communities were tired of dead animals and rotting refuse washing up on their shores.

The end of ocean dumping triggered a shift to local landfills and incinerators – most notably Fresh Kills on Staten Island – which dominated until the turn of the century. Engineered in part by divisive master-planner Robert Moses, many of these projects reshaped the coastline and plagued neighborhoods for decades. By 1955, Fresh Kills was the largest landfill in the world—in fact, one of the largest human-made structures on Earth—and was later rumored to be visible from space. By the 1960s, the city had 22 municipal incinerators and more than 17,000 apartment building incinerators. As political pressure and environmental concerns mounted, all of these sites were eventually closed.

By the time Fresh Kills was closed in 2001, it had taken in more than 150 million tons of garbage and become New York’s last remaining option for handling its own waste.

In his book, “Fat of the Land: Garbage of New York – The Last Two Hundred Years,” Benjamin Miller estimated that Fresh Kills had at least another 15 years of capacity left. Without a feasible contingency plan for what came next, the city’s waste management system was thrown into chaos. “It would be impossible to do things worse than we have done them in recent decades,” says Miller.

The SWMP solution

More than 14 years after the closure of Fresh Kills, the city’s system for collecting and transporting trash is still adapting.

A large portion of residential and commercial waste is currently handled through land-based transfer stations where it is put into long-haul trucks bound for landfills. Three rail transfer stations also handle residential waste. Once a fourth rail transfer station opens this summer in Queens approximately 58 percent of the waste handled by DSNY will be exported via rail or barge.

DSNY’s current guiding policy is the city’s 2006 Solid Waste Management Plan (SWMP), a major legislative accomplishment by the Bloomberg administration that called for overhauling six defunct marine transfer stations (MTS) to begin shipping garbage via barges.

Nearly 10 years in, only one MTS is fully operational.

The North Shore MTS opened in College Point, Queens this year and will be at full capacity by summer. The Hamilton Avenue MTS near Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal is almost complete and expected to open next year. The 59th Street MTS in Manhattan is currently handling paper, but is scheduled to be shut down for a renovation so it can process construction and demolition debris. That can’t happen until the Gansevoort MTS in Chelsea is built to process recyclables, though permits for that project have yet to be approved by the state government. The remaining two stations, Southwest Brooklyn in Gravesend and East 91st Street in Yorkville, are in the early stages of construction.

The final two have both inspired fierce opposition, but East 91st Street is by far the most contested. Residents have been fighting the station with lawsuits, protests and electoral efforts for years. They say that the station is in a more densely populated residential area than any of the others and will have a minimal effect on the overall distribution of city garbage processing.

The common argument behind the East 91st Street MTS is that Manhattan produces 40 percent of the city’s waste but handles none of it. While this is true, a large percentage of that waste is commercial, which isn’t guaranteed to come through the MTS because tipping fees will be higher than current transfer stations in other boroughs. Otherwise, the MTS will handle waste from four community districts whose trash is currently being trucked to New Jersey.

“What we’re doing by shifting garbage is like shifting the chairs on the deck of the Titanic. We’re not solving the problem here,” says Kelly Nimmo-Guenther, president of MTS opposition group Pledge 2 Protect.

She argues that in light of the mayor’s new waste reduction goals, the MTS is less necessary than ever. The Independent Budget Office estimates that by the time the station is open it will cost about three times more to tip garbage there than originally anticipated.

Despite all of this, construction is underway and the MTS is scheduled to be operational in 2017. A potential compromise over placement of the ramp is possible—which could alleviate concerns about pedestrian safety—but has raised new issues. Pledge 2 Protect supports the idea of moving the ramp, but still opposes the MTS. The Asphalt Green recreation center has moved on from trying to stop the MTS and is leading a campaign to move the ramp one block north to East 92nd Street.

Demetrius Freeman/Mayoral Photo Office

De Blasio presents his OneNYC vision, the first attempt by the city to address its waste problem since the Bloomberg administration's SWMP in 2006.

“It’s not under our control whether there’s an MTS or not, but we can do something and speak up and let the mayor know this is such a good solution,” says Maggy Siegel, executive director of Asphalt Green.

This would put the ramp one block closer to NYCHA’s Stanley M. Isaacs Houses. Some residents fear that could divert traffic entering and exiting FDR Drive in a way that would create more congestion around their complex. They have since split off from the other groups to fight both the ramp and the MTS on their own. The area has some of the highest asthma rates in the city.

“Sometimes you have to swim by yourself,” says Rose Bergin, president of the Stanley Isaacs Houses Tenant Association. “They’re killing us quicker if they open this.”

A decision about relocating the ramp is expected from the mayor’s office soon.

Meanwhile, Gravesend residents are fighting the Southwest Brooklyn MTS with equal vigor, though less attention. That MTS is set to be built on the site of a former incinerator along the waterfront. Opponents of the plan are worried that residual contaminants from the incinerator—such as mercury and lead—may be disturbed during dredging for construction. The potential presence of munitions lost during a 1954 naval accident is also a concern. DSNY has acknowledged these issues but says they can be mitigated, and has received approval to proceed from the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

“This is, in my opinion, one of the worst environmental decisions that has been made in New York City,” says Council Member Mark Treyger, who represents a neighboring district.

Assemblyman William Colton filed a lawsuit to stop construction, which was dismissed. He has since filed an appeal. Colton, Treyger and other community members have held multiple protests. Treyger thinks their case is stronger now since the mayor’s waste reduction goals were announced.

“I respectfully ask if that’s the goal, why are we spending billions of dollars and building new waste transfer stations in residential neighborhoods?” he says.

Benjamin Miller says the idea of taking garbage to the shoreline dates back to the days when horse carts used to dump it directly into the water or onto barges. The city continued this practice for years by sending barges to Fresh Kills, but the process is no longer the most efficient option since the waste will still end up getting transported to landfills via rail or truck. “We could put it right on a rail car in every borough,” he says.

Building state-of-the-art marine transfer stations, with the extra step of cranes putting containers onto barges, has become very expensive. The total construction cost for these stations is approaching $1 billion.

“The day the Solid Waste Management Plan was passed in 2006 it was already obsolete,” says Council Member Ben Kallos, who represents the neighborhoods around the 91st Street MTS.

He has joined a long line of local politicians that have taken up the cause. In a March 25 preliminary budget hearing at City Hall, he grilled DSNY Commissioner Kathryn Garcia over rising construction costs. Her response was measured, but indicative of the plan’s changing relevance in recent years.

“As I’ve testified before, the Solid Waste Management Plan is a very expensive choice. It’s a choice that was made because of the fact that there were certain neighborhoods that historically had taken more refuse, and in order for there to be a vision of borough equity, there were very, very expensive decisions made and very expensive contracts signed for long durations. So the fact that it’s very expensive is not surprising,” she said.

Adi Talwar

A low recycling rate, dwindling landfill space, the cost and carbon footprint of long-distance hauling and the impact of transfer facilities on the neighborhoods that house them are just some of the problems facing New York's trash system.

Still battling over transfer stations

Yet for environmental justice advocates, even one less truck that goes to a transfer station in the South Bronx, northern Brooklyn or southeast Queens will make the SWMP worthwhile.

“It’s pretty hard to see any other system that’s as blatantly discriminatory as our solid waste system,” says Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance. “It’s just night and day when you look at the disparity.”

Pedestrian safety and illness related to diesel fumes are some of the greatest concerns around heavy truck traffic going to transfer stations. The South Bronx has been shown to have the highest pediatric asthma rates in the city.

Bautista has been fighting efforts to relegate waste transfer stations to these communities for nearly 20 years. He views Mayor de Blasio’s OneNYC announcement as the halfway point of a very long campaign for environmental justice in waste management.

“It’s now turned into a generational fight,” he says.

One of his latest battles is to reduce the amount of land-based transfer stations in these three neighborhoods and put a cap on how many stations other neighborhoods can host in the future. Currently, the majority of commercial and a large portion of residential waste travels through these stations. The need for them will decrease once all of the marine and rail transfer stations are complete. Intro-495, a piece of legislation currently being negotiated in the City Council, would codify these changes. So far, resistance from the commercial waste industry has been strong.

Antonio Reynoso, chairman of the City Council’s sanitation committee and one of the bill’s primary sponsors, has tough words for those who don’t want to cooperate.

“In sanitation everything is difficult. There’s no win-win situations. There’s just hard choices to be made for the greater good,” he says. “This is one of those pieces of legislation that for some it’s gonna be hard to swallow, but overall the city’s gonna be better for it.”

These siting battles over transfer stations have dominated the local waste debate for over a decade. As vital as they are to the neighborhoods they affect, they do not fully address the mounting problems facing the city’s waste management system—cost, carbon emissions and equity—not just in New York, but also in the faraway towns the city dumps in.

“At a certain point the pain has got to kick in,” says Benjamin Miller. “Do we really want to be dumping this in landfills in somebody else’s backyard?”

With research assistance by Liridona Duraku.

31 thoughts on “New York’s Garbage System Faces Mounting Challenges of Cost, Carbon and Equity”

The only place that Fresh Kills had 15 more years of dumping capacity was in Benjamin Miller’s imagination. In it’s last years of operation the smell of garbage reached all the way to the east shore of SI, 5 miles away.

I understand why the locals are fighting the transfer station on East 91 Street. That is a very nice area that won’t be improved by it’s placement there. My advice to them is believe absolutely nothing that the DSNY tells them. DSNY was never able to mitigate the smells emanating from Fresh Kills because they never even tried.

Not totally true about every borough handling it’s own waste. Some paper from Brooklyn is sent to the Visy recycling plant on Staten Island. And some garbage barges from the other boroughs are apparently still (illegally) brought to the SI transfer station where it is loaded onto sealed rail cars and shipped across the Arthur Kill liftbridge to NJ. The rail line even has grade crossings (photo: Chelsea Road), among the few in NYC.

Until recently Eddie Bautista was so laboring under his desire to stick in to what he perceives as the rich Upper East Side – but is actually Yorkville – he was unaware that 5 NYCHA buildings and thousands of residents live within 300 feet of this proposed horror. But then, these 5 towers were constructed where they are when the previous garbage dump incarnation was in operation because who cared if poor people were exposed to tons of garbage. Folks like Bautista and our mayor still don’t care as long as ideology is served. So what if not a shred of Manhattan’s residential waste is inflicted on other boroughs? So what if we send ton upon ton of our garbage hundreds of miles to be landfilled near still more poor people? So what if at least 4 recent studies connect particulate matter in vehicle – i.e. garbage truck – exhaust with ADHD and autism? So what if the rest of the world has moved on to such state-of-the-art recycling and 99.9% clean waste-to-energy that countries like Norway now import trash from erstwhile Russian satellites and cities like Copenhagen are constructing center urban W-to-E plants with ski runs wrapped around them? Really. What century are those we’ve entrusted with our great city living in?

There is no such thing as “99.9% clean waste-to-energy.” Waste cannot be turned into energy, but only into toxic ash and toxic air emissions, in horribly expensive facilities called trash incinerators that produce fairly little energy… 3-5 times more energy is saved by recycling and composting those same materials… you can’t get it all back by burning them.

It’s a myth that incinerators are clean in Europe. They’re polluting there, too. However, the reality in the U.S. is that they’re among the worst polluters we have, worse than coal by every available measure. The main one where NYC waste will be going for the next 20-30 years (in Chester, PA) is the largest in the U.S. and lacks the basic pollution controls most have. Not surprisingly, it’s in a poor, black community with a heavy concentration of other industrial polluters as well.

Learn more here: http://www.energyjustice.net/incineration/

Are we feeling a shill for Waste Management?

Not sure what you’re feeling, but if you’re implying anything about me (Mike Ewall) or the Energy Justice Network that I direct, you couldn’t be more off-base. First company I’ve ever fought (starting in 1991) was Waste Management, Inc. and their incinerator and landfills in my home county in Pennsylvania. Been helping people fight them and their various subsidiaries ever since, including a multi-state nuclear waste dump we stopped in the mid-1990s, a hazardous waste incinerator we failed to stop, and numerous incinerators and landfills that we helped people successfully defeat, including an incinerator stopped in Frederick, MD just last year after an 8-year fight. So, maybe someone else is shilling for industry here, but you’re barking up the wrong tree if you think I or Energy Justice has any such conflicts of interest. Never did and never will.

Read up, friend:

http://www.wien.info/en/sightseeing/green-vienna/vienna-power-plants

http://www.wien.info/en/sightseeing/green-vienna/vienna-power-plants

http://www.dac.dk/en/dac-cities/sustainable-cities/all-cases/green-city/copenhagen-is-the-2014-european-green-capital/

http://www.archdaily.com/339893/bigs-waste-to-energy-plant-breaks-ground-breaks-schemas/

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2013/08/130801-amager-bakke-europe-waste-to-energy/

Nobody’s saying waste-to-energy is perfect… yet – but the alternatives?

NYC’s already been successfully sued by the poor of NC residing next to some of the thousands of acres encrusted with our waste.

I’m already very familiar with the PR about these “beautiful” incinerators in Europe. It’s still unavoidably expensive and polluting. The more pollution controls you add, the more prohibitively expensive it becomes, and the toxins don’t vanish… they just move from the air to the ash that has to be landfilled. The ones in the U.S. are already the most expensive way to manage waste (see the industry’s own data) or to produce energy (see the Energy Information Administration’s data). I summarize and link to the data here: http://www.energyjustice.net/incineration

I’d be interested to see what lawsuit you’re talking about from NC. Care to share a link?

Also, care to stop being anonymous and say who you are? Do you have any connection to the industry?

I believe the Niagara Falls facility chooses not to use filters 3-5 for emissions due to cost factors, I am working off memory however will verify if need.

Your actions are those of a true enemy of mankind.

Sequestering carbon for greater use or upcycling is the future of our waste streams. To spend roughly $.18 for $.12 of electricity is not a sustainable model regardless of the negative effects incineration has on the environment and the populations. With Innovative competitions in full swing and a concerted effort for adaptations to occur from EPR to ZERO WASTE INITIATIVES, we are getting closer to a new way of doing business. See “REIMAGINE PHOENIX” for an example of city efforts combining tech advances with university think tanks!

How about we only use products that are recyclable, glass instead of plastic

“The single worst thing we could possibly do with garbage is landfill” – WRONG. The single worst thing NYC could do is incinerate waste, as incineration is the most expensive and polluting way to manage waste (or to make energy). It is NOT “zero waste to landfill” since the toxic incinerator ash still goes to a landfill — ensuring that there are smaller, more toxic landfills, after poisoning the air.

The worst thing NYC could do is what it did… sign a 20-30 year contract to burn the waste in a poor, black community in Chester, PA (near Philly) – home to the nation’s largest trash incinerator and surrounded by a myriad of other polluters, including a sludge incinerator, oil refineries, chemical plants and oil/gas power plants. The incinerator lacks the basic pollution controls that most have, including the ones used to remove nitrogen oxides (NOx) that cause asthma, which is the main reason the incinerator is one of the top NOx pollution sources in the entire eastern half of Pennsylvania. Chester has a childhood asthma hospitalization rate three times the state average. Of all 80-some trash incinerators in the nation, the one in Chester is the worst for particulate matter air pollution, #3 in sulfur dioxides and #6 in mercury.

More crazy is that the transportation plan is a mess. Trucks currently go from Manhattan to the incinerator in Newark (which is also a serious problem). The plan would have them go to the E. 91st Marine Transfer Station, transfer them (with diesel cranes?) to dirty diesel barges to ferry them through the city (most diesel exposure for some of the most polluted parts of the city) to Staten Island, to then transfer them to trains. Half of those trains will bring waste to be burned in Covanta’s incinerator in Niagara Falls, NY. The other half will go through NJ, through Pennsylvania (Philly, then through Chester) to Wilmington, DE, where they’ll be put on trucks to be trucked back into Chester, PA to be burned, poisoning the air and causing asthma, cancer and more. The resulting ash will then be trucked an hour away to the “Rolling Hills Landfill” near Reading, PA to poison the groundwater there.

The 20-30 year contract the city signed will lock the city into paying a certain minimum amount, stifling any real zero waste plan. However, we know this isn’t a real “zero waste” plan, since incineration is the first thing that comes off the table in any real zero waste plan.

For more info, see:

http://www.ejnet.org/chester – on Chester, PA

http://www.energyjustice.net/incineration – about incineration

http://www.energyjustice.net/zerowaste – about zero waste

Right on the money! Please look into the Niagara Falls dilemma. With Covanta’s bid for a 30Mil upgrade to handle the increase in NYC waste, the increase in neighborhood decline will accelerate. We are hoping IBM / Robert Watson will have enough support to bring the ECOHUB to NYC. As in Houston, see ECOHUB-HOUSTON.COM Good luck to all of us!

I am extremely skeptical of a rail-based option for Manhattan given the level of rail congestion coming out of the city.

Can anyone show a viable alternative to the barges? Otherwise the opposition is just NIMBY-ism.

The MTS plan IS rail-based – after hauling waste by polluting barges & tugs. The plan will transport NYC waste by barge & rail at triple the cost of the current system to poor cities hundreds of miles away to be burned in out-of-date & poorly filtered incinerators. This plan will add $ billions in costs and strap NYC to a fixed & obsolete system exactly when we need maximum waste management flexibility to meet the progressive zero waste goal just revealed in the OneNYC plan.

The MTS plans are obsolete, and outrageously expensive to the taxpayers of the city. The thought that trucking the thousands of tons of waste generated in midtown to a small neighborhood filled with kids and seniors, by hundreds of polluting trucks, to dump them in a facility that is YARDS from both a kids playing field, a toddler playground, and NYCHA homes, on to barges that use a grade of diesel that is way more polluting then the trucks that already traveled all over town to get to Yorkville — that that is environmentally sound is insane! No outer borough community will be impacted as this article states, since the thousands of carting companies will still take their loads to the Bronx or Queens, or wherever its cheaper to tip. The MTS belongs in NO BACKYARD.

It breaks my heart to see kids playing sports on a field that will soon be lined up with garbage trucks. They emit diesel fumes, which was recently classified as a Class A carcinogen. Running fast, breathing hard, and inhaling all that cancer causing exhaust. The kids (of all races and economic backgrounds by the way) will get sick and suffer, all in the politically-motivated name of justice. Brilliant billion dollar boondoggle, Mr Mayor and Mr Bautista.

Pingback: Mayor DeBlasio’s Garbage Failure | yorkvillewalkers

Pingback: Pledge 2 Protect – Via CityLimits.org: New York’s Garbage System Faces Mounting Challenges of Cost, Carbon and Equity

I live near the East 91st Street MTS construction site and am devastated to see the work progressing there. To think of the dangers–both environmental and safety-related–posed by the MTS (and the quantity of garbage trucks it will generate coming in and out of the neighborhood) is devastating. This is a residential neighborhood and a street where playgrounds, swimming pools, and ball fields sit. It’s a tragedy in one of NYC’s gems.

The Yorkville transfer station, or any transfer station in a highly residential area is clearly a wrongheaded decision. The environmental dangers of a flood of garbage trucks idling on the streets where there is congested housing, open parks where thousands of children play, and many schools where children attend has been well documented. The fact that this method of disposal is non-sustainable and that funds that could well be used to research and create sustainable solutions to a growing crisis are being literally poured into short term “solutions’ that will harm an entire generation, displays either arrogance or political motivation. Is it not time that construction on this collection station be stopped, the money flow staunched, and mayor and his administration show innovative leadership before they allow a community to suffer because they cannot find the answer to a problem that eventually will have to be answered.

The City must stop wasting billions of dollars on transfer stations that are not the answer for today nor the future. Taxpayer dollars should go to programs that will actually reduce waste and reduce burdens placed on New Yorkers.

Bloomberg’s plan for a Garbage Dump @ East 91st Street was supposed to be “Grandfathered In” legally that means built “In the Footsteps of the original Garbage Dump”. However the new Marine Transfer Station is not even near the old one and it will be 10 stories tall, making it an illegal project! In addition, the law states that a Garbage Dumo cannot be built closer than 500′ to a residential community. This one is being built 300′ from a residential community also making it illegal! Our “ONE TERM Mayor will not listen to reason. he knows that what he is doing is WRONG yet his ego will not let him DO THE RIGHT THING AND STOP CONSTRUCTION NOW!!!

My 92 yr-old friend and I walked to Asphalt Green Center on York Ave at 92nd St today to check out a swimming class for elderly folks with arthritis. As we crossed York Ave on our way back, it was fully congested with traffic entering the FDR Drive a block north and with the 2 city bus lines that turn right there on 92nd Street. As I made my way across the street, my friend, who uses a walker, yelled at me not to cross. She couldn’t see through the cars that the light had changed. As I crossed, so did scores of children and mothers coming from the nursery and Asphalt Green Center. Try as I may, I can’t square adding 500 garbage trucks daily in this same 2 block area with Mayor De Blasio’s goal of zero traffic deaths!

What is the logic of building a $1B Waste Transfer Station that will cost exponentially more to dispose of trash than the current waste management solution? Moreover, it does not bring any environmental benefits and the transfer station is being built in a residential flood zone!

It’s time to spend taxpayer money on more prudent projects which bring environmental benefits and improve lives, please stop the 91st Street Waste Transfer Station.

It’s just trash. Who cares? The name is “the Sanitation Department” so maybe folks should stop whining about what they throw away and why there Sanitation Department isn’t keeping the sidewalks clean? Trucks with pressure washers, rainwater collections, creating green spaces…that’s what Sanitation should be about…it’s your tax dollars and your Government Agency….actual refuse volumes have collapsed since Lehman and Madoff…maybe folks should just stop paying and see what happens.

I’m from Jersey, and I’m just kind of laughing at the people who are fighting the transfer stations. You’ve been doing this to us for years. Keep your own trash, we’re sick of it.

WELCOME TO THE THIRD WORLD:

The correct answer for all those looking for the correct is to use all that crap in a manner so that it needs not be shipped anywhere:

But how can the now non-industrial centre of the center of the thin skinned indulgent spoiled entitled consumerist economy of a privileged country based on the gluttonous usage of capitalist consumption change decades or perhaps centuries of policies based on the class society where Democrats and Republicans agree for the most part on preservation of its decadent cesspool of inequality that is imposed worldwide?

Oh and the current state of the recycling industrial of many vested interests represents the worst as it sells materials as any third world does.

I’ve just read through the comments and noticed a lot of complaints…but no solutions. No, I don’t have the “silver bullet” as mentioned by Steven Changaris in the article, but something not discussed in the article or in the comments is education. This could be an education problem.

How many New Yorkers really know that trash is a problem? How many of them know and don’t care? AS the saying goes, “out-of-sight, out-of-mind.”

I admit I don’t know a lot about this issue, so I apologize in advance if I’m off-base. I don’t recall seeing any ad campaigns encouraging the general public to reduce how much they throw away (other than in the subway…track fires, eesh!) and I don’t know of any tax-benefit large corporations receive for producing less trash than other companies of similar size. If this is really a billion-dollar issue, I think a 5% or 10% reduction in waste could make a big impact, especially if it becomes a way of life for all New Yorkers. If we produce less trash, we’ll need less MTSs, less trucks, less tugs and barges, etc. The only players that lose are the companies getting paid to transport/burn/bury the trash.

Really very nice and informative article !!! thanks for sharing!!!

waste management collection

Waste management systems are one of the tougest work to do by the government. I think USA is failing to coup up with this problem. All our tax paying money is going to wars. Nowadays roads are also not maintained properly. If you want to see neat and clean roads and proper waste management system. Visit Dubai.