Gov. Kathy Hochul recently signed the Health Equity Assessment Act, which advocates say will help address the impact of decades of hospital closures and consolidations across the state, which left certain communities—primarily low-income and neighborhoods of color—underserved when it comes to health facilities.

William Alatriste/NYC Council

A 2010 rally to stop the closure of St. Vincent’s Hospital in lower Manhattan.When St. Vincent’s Hospital closed its doors in the West Village for the last time in spring 2010, neighbors and public health experts questioned where its patients would now go instead. How much further away is the next ER? How many minutes might it add to a patient’s trip in a potentially life-threatening situation?

Those questions arise each time a hospital closes, or shrinks: Like when Harlem’s North General Hospital shut down in 2010, or Peninsula Hospital Center shuttered in Queens in 2012, or when Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center closed its inpatient services this past summer, part of its merger with two other East Brooklyn hospitals.

Over the last several decades, dozens of hospitals across the state have shuttered, consolidated with larger providers or pulled back services. In 2006, there were 71 hospitals in New York City alone, City Limits reported at the time; the state’s Health Department today lists just 59.

READ MORE: Decades of Shrinking Hospital Capacity ‘Spelled Disaster’ for New York’s COVID Response

That shrinking network forces other nearby hospitals to pick up the strain—often safety net providers or public hospitals, where patients are more likely to be uninsured or on Medicaid—and leaves some neighborhoods with fewer healthcare resources than others.

Queens, for instance, has only 1.5 hospital beds for every 1,000 residents, compared to 6.4 beds per 1,000 people in Manhattan, according to one analysis. Those differences became even more visible—and consequential—during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which Queens was particularly hard hit. During the early peaks of the crisis, officials scrambled to increase hospital capacity, setting up beds at the Javits Center and clearing CUNY dorms for use as potential medical facilities.

“The COVID-19 impact made it really clear that hospital beds and other healthcare resources are not distributed equitably around the state,” said Lois Uttley, coordinator at Community Voices for Health System Accountability (CVHSA), a coalition of public health advocates.

New legislation, signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul last week, aims to address that by changing the Certificate of Need (CON) process, the state’s main mechanism for overseeing healthcare facilities. The Health Equity Assessment Act (S.1451A / A.191A) will require any hospital or clinic applying for a CON—through which the state grants approval for major changes like a closure, merger, downsizing or new construction—to assess the impact that change will have on the communities a facility serves.

Under the law, providers will have to file a “health equity impact assessment” looking at how its plans might effect certain medically underserved groups, like low-income residents or New Yorkers with disabilities. “In some ways, you could analogize it to an environmental impact statement,” Assemblymember Richard Gottfried said during a hearing on the bill in June.

Experts and advocates say it will help officials better plan for a more equitable allocation of health resources around the state, and give patients an indirect voice in decisions that could impact their care.

“Currently, the state process of reviewing and approving and disapproving major health facility transactions is not transparent, or consumer-friendly,” said Uttley. There are no public hearings; CON decisions are ultimately made by the health commissioner and state’s Public Health and Health Planning Council (PHHPC), which critics say is disproportionately made up of health care executives rather than patient advocates.

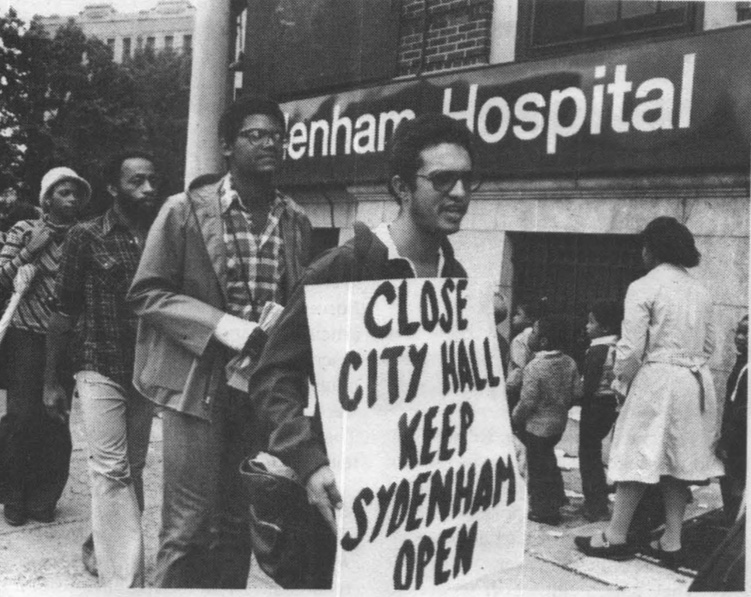

Laurie Peek/City Limits’ Archives

Demonstrators protest the closing of Sydenham Hospital in Harlem, which shuttered in 1980.The Health Equity Assessment legislation represents “a major step forward” in terms of “getting the voices of affected communities into the conversation,” Uttley added.

While Hochul only signed the bill last week, it was passed by lawmakers at the end of the legislative session in June; five reps voted against it in the Senate, and seven members opposed it in the Assembly. That included Assemblyman Kevin Byrne of the Hudson Valley, who said he was worried the legislation would “prolong an already burdensome” CON process and make it harder for health care facilities to grow.

“When we’re at a time trying to increase health care capacity, I’m not sure this is the right way,” he said during a June hearing on the bill.

Assemblymember Andy Goodell, a Republican who represents Chautauqua County, expressed similar concerns at the same hearing.

“I’ve had hospital administrators come to me and point out that their private physician groups were able to quickly buy the latest imaging technology or the laboratory equipment or set up a satellite office all done, designed, build, ordered, paid for, constructed before the hospital could get to first base on the CON process,” he said, according a transcript of the meeting.

But Gottfried, the bill’s sponsor, countered that the impact assessment is not expected to greatly complicate CON applications, and that the legislation exempts smaller community health centers that largely serve low-income patients.

Uttley and other supporters argue the new law will give the state more leverage in the CON approval process, to better look out for “the people who live in that community and depend on that hospital for care.”

“It makes more visible what the impact might be,” she said.

READ MORE: