Brooklyn tenants are trying to dismantle barriers around a seldom-used 1960s-era law that can prohibit landlords from collecting rent when they fail to fix dangerous building conditions for months on end. The campaign just had its first breakthrough.

Adi Talwar

Beverly Rivers in front of her apartment building in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn.Beverly Rivers has lived at 125 Lenox Road in Flatbush for over 30 years. At 67 years old, she’s raised two daughters in her apartment.

So she was relieved this month when a housing court judge dismissed her eviction case, ruling that her landlord, One Lenox LCC, couldn’t collect back rent. Not just the nine months she was sued for, but more than a year’s worth—a time when dangerous conditions plagued Rivers’ building. “It felt good because I was going crazy,” she said.

Rivers benefited from a little-known section of the state’s Multiple Dwelling Law, 302-a, which can prevent a property owner from seeking rent once they fail to fix a dangerous situation, deemed “rent-impairing,” for at least six months. It could be a fire hazard, or one of dozens of other conditions deemed a “serious threat” to life, health or safety.

It is otherwise rare for tenants to have months of rent obligation wiped out as a result of building disrepair, not simply reduced. According to landlord attorney Lisa Faham-Selzer of Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens LLP, property owners take notice.

“Landlords don’t want to have these violations,” she said. “And it scares them into keeping the apartments up to code.”

In Rivers’ case, city inspectors identified a defective fire escape as well as illegal door and gate fastenings endangering the whole building—court records show these violations were fixed in January—plus a rodent infestation in her apartment.

One day last October, Rivers went to use the bathroom and encountered a rat. She managed to capture a video. “I see these two eyes glaring at me. Oh lord, I froze,” she recalled. “Needless to say, I was so petrified I couldn’t do anything I went in there to do.”

Beverly Rivers

Screenshot from a video Rivers captured of a rat inside her bathroom, on Oct. 15 of last year.Rivers’ win constitutes the first breakthrough in a coordinated campaign across five buildings in Brooklyn, where tenants are organizing with their neighbors to fight eviction and win meaningful repairs, supported by Housing Organizers for People Empowerment, or HOPE, and Flatbush Tenant Coalition, among others.

They’re trying to work around what advocates deem flaws baked into 302-a. While a serious rodent infestation can qualify as rent-impairing, other conditions, like an obstructed fire exit, are not always apparent to tenants. It helps to have a lawyer who can comb through city records looking for violations marked with a telltale asterisk. Any rent paid while the condition exists is water under the bridge.

And most significantly, a tenant has to present the money their landlord is suing them for up front before they can potentially win it back under the law. While the strategy can work smoothly for tenants of means, low-income New Yorkers are less likely to be able to use it.

Rivers herself, who lives on social security, would have been stuck if not for a novel strategy involving recyclable funds.

“I think for the tenants it’s this idea that feels very natural—the landlords should have to forfeit 100 percent of the rent if they’re not making repairs to these extremely dangerous conditions,” said Catherine Barreda of Brooklyn Legal Services, one of Rivers’ lawyers. “It feels satisfying and feels right morally, but for the rent deposit requirement.”

Hope and disappointment

Brooklyn Legal Services

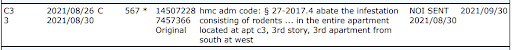

A screenshot of one of Rivers’ violations, pertaining to a rodent infestation. The asterisk designates it as rent-impairing.There are currently about 136,900 rent-impairing violations across New York City, according to city data reviewed by the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. About 119,500 of those have been open for at least six months—the point at which a landlord might be barred from collecting rent.

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development, or HPD, which issues these violations, cautioned that they can stay open even after being fixed if landlords don’t formally register the correction with the city. Looking at violations issued in the last five years that have passed the six month threshold, the figure drops to about 47,650.

Yet courts spokesperson Lucian Chalfen told City Limits that rent-impairing violations are rarely used as a defense against eviction: “It’s a hard defense to raise, because it requires that the tenant deposit all the money demanded in the petition with the court and tenants rarely do that.”

Douglas Kellner is a lawyer in private practice who represents tenants. He estimates he’s litigated rent-impairing violations a few times per year going back to the 1970s, often in conjunction with a rent strike. “It’s sort of an open and shut issue—either the violation is there or it isn’t,” he told City Limits.

But Kellner typically works with clients who earn enough to set all of their withheld rent aside in escrow. “In organizing tenants we’ve always taken a pretty hard line,” he said.

Low-income tenants can’t necessarily do this. Rivers told City Limits that the deposit requirement is unfair. “Because not everybody has that money to pay,” she said. “And all this happened in the time of the pandemic, you know? And a lot of people lost their jobs, couldn’t go to work, got sick, and all these things.”

To address this, the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, or UHAB, is administering a revolving fund. What started out as a crowdfunding effort in early 2021 now has about $155,000, according to the organization, put forward primarily by the Robin Hood Foundation and North Star Fund.

Brooklyn Legal Services was able to use about $8,000 from the fund to launch Rivers’ defense—most of which will return to the pool for others to use, now that the court has ruled in her favor.

Another 13 tenants have also drawn on the fund, though they have yet to win their deposits back. Some are on rent strike with their neighbors and could compound their leverage with this tactic, helping to win repairs and some level of rent cancellation.

But even as the strategy begins to bear fruit, advocates say it’s imperfect. Tenant lawyers have been butting heads with landlords and judges for months, disputing how Section 302-a should be applied—complex and time-consuming work for attorneys juggling heavy caseloads. The revolving funds get locked up in lengthy litigation.

Ideally, some say, state law would be amended to remove the deposit rule, which perpetuates the idea that only some tenants deserve safe apartments. Jenny Akchin, an attorney with TakeRoot Justice, sees a fundamental fairness issue with the law, indicative of a prevailing attitude she’s encountered in housing court.

“It’s just one of the many ways the courts shift the burden always onto tenants, and particularly tenants of low income—‘Why aren’t you paying the rent? Why don’t you have the money?’” she said. “Instead of asking landlords, ‘Why aren’t you fixing the rent impairing violations? Why is the fire escape locked?’”

Back to the beginning

Passed in 1965, the rent-impairing violation law was intended to be a strong motivator for landlords to make repairs at a time when tenants had little recourse.

In a letter to Gov. Nelson Rockefeller’s office, sponsoring Assemblymember S. William Green said that the purpose of the bill was to “force landlords in residential buildings where there are serious violations to cure those violations.”

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York drafted Green’s bill, along with the Community Service Society (a City Limits funder). In a 1963 memorandum, the bar association predicted that it would put real economic pressure on landlords, with a deposit requirement to deter tenants “seeking new excuses for nonpayment of rent.”

Faham-Selzer, the landlord attorney, sees utility in the deposit requirement today.

“It should be, a tenant would pay the rent but for a rent-impairing violation,” she told City Limits. “The tenant is willing and able to abide by their side of the agreement with the landlord, and the landlord is not abiding by their side.”

But advocates counter that just because a tenant doesn’t have all of the money on hand to deposit with the court, doesn’t mean they should be excluded, or won’t be able to pay rent going forward. They may have dipped into savings to do their own repairs. One ill-timed emergency, like a death in the family, could put the strategy out of reach.

“When you’re living paycheck to paycheck and things are tight anyway, you don’t have a lot of room for error,” said Ryan MacDonald of TakeRoot Justice, Akchin’s colleague.

It further discriminates irrationally against the poor, predominantly racial minorities, by making unavailable to them affirmative defenses which are available to the wealthy.

-Excerpt from 1973 lawsuit challenging the deposit requirement in 302-a

Tenants who can’t use the defense often end up settling with their landlords and seeking government assistance to cover agreed-upon debts, he added: “You’re having the state essentially pay for a building or apartment in terrible condition.”

Rivers and her fellow tenants are not the first to question the fairness of the deposit rule. In a 1971 decision in a Manhattan eviction case, Judge Leonard Sandler found that it violated due process to require tenants to deposit the amount of money their landlord was seeking before they could find out if the amount sought was even correct.

“[T]he New York Legislature has effectively deprived tenants of the use of their own money for indefinite periods of time without any prior opportunity to be heard,” Sandler wrote in his decision.

A few years later, MFY Legal Services sued the state in federal court on behalf of a proposed class of tenants, arguing that the deposit requirement violated their due process and equal protection rights.

“It further discriminates irrationally against the poor, predominantly racial minorities, by making unavailable to them affirmative defenses which are available to the wealthy,” the complaint stated.

But the argument sputtered. The court found that tenants could make smaller deposits if they believed they’d already paid some of the money sought, alleviating concerns about unconstitutionality. Appeals to the Second Circuit and Supreme Court failed.

Court frustration

For those with cash on hand, tenant lawyers say using the rent-impairing violation law should be straightforward. If a violation is recorded by HPD, and has been open for at least six months, a tenant facing eviction can deposit “the amount of rent sought to be recovered in the action,” as the law states, and ask the judge to rule, no trial required.

But the strategy has proven more complicated in practice. “We’ve had issues with the clerk’s office [in housing court] and even depositing the money,” said JohnAugust Bridgeford, an organizer with HOPE.

Landlords have also disputed the appropriate deposit amount, contested how long certain violations were open, and accused tenants of delay tactics. At a time when lawyers are in short supply for tenants, dedicated representation has proven crucial.

In Rivers’ case, her landlord tried to sanction Brooklyn Legal Services, accusing the organization of disingenuously trying to pause the case, buying time to make their deposit. The attempt failed, but Judge Hannah Cohen issued a warning. A Brooklyn Legal Services spokesperson said they “vehemently disagree” with how their work was characterized; the landlord’s lawyers did not respond to requests for comment.

In another instance, Judge Cohen ordered tenants in two apartments at 1402-08 Sterling Place in Crown Heights to increase their deposits, after they raised the rent-impairing violation defense over since-resolved issues: a gate blocking a passageway in one building, a roof leak and fastening on a fire escape in the other.

Adi Talwar

Residents of 1402-1408 Sterling Place meet with their HOPE organizers to strategize their fight for repairs on March 19.Lorna Elliot and her husband Keith had saved about $9,000 of their own money—the amount their landlord, Chestnut Holdings, had initially sued them to recover. They are among 14 families across the two buildings who have been on rent strike since last April over a litany of issues including rats, mice, roaches and leaks.

“We work, and we believe in paying the rent,” Lorna told City Limits this spring. “We don’t believe in scamming the landlord. This [apartment] is his, that’s not ours, and we have to pay for it, but it’s just that we need better treatment.”

Counsel for Chestnut Holdings disputed the repair timeline for the building-wide rent-impairing violations in court papers, noting that some were issued “at the height of the covid-19 pandemic,” making it difficult for city inspectors to visit and dismiss them.

“Chestnut Holdings has and continues to work diligently to address maintenance issues as well as engage in building wide improvements in all its buildings,” the company said in a statement. “Unfortunately, in a limited number of cases, residents use common legal tactics in housing court to reduce or attempt to eliminate their rental obligations.”

Judge Cohen ultimately ordered the Elliots to deposit the amount owed when they first raised the rent-impairing violation defense, five months into the case—by then nearly $11,500. She ordered their neighbor Ms. June to more than double her deposit by the same logic, to over $13,500, citing the standard set in a 2009 appeals court decision.

Attorneys with TakeRoot Justice had to scramble to cover the difference with the revolving fund—money they say could have helped other tenants in the near term. This is one example of judges throwing up additional barriers when the law is already difficult to use, according to Akchin.

“We had tenants who literally did everything right, raised the defense, had the deposit on hand, and then [Judge Cohen] said, ‘But you didn’t pay all of the rent,’” she said.

Looking ahead

Despite their frustration with the law and how it’s been interpreted, tenant organizers say they’ve gotten a glimpse of what real leverage looks like.

Over on Lenox Road in Flatbush, Rivers says she’s still dealing with rats. She hears them in the walls at night, and recently snapped a photo of one in the lobby. (Attorneys for One Lenox LLC did not respond to inquiries about the photo, or rats in general.)

Yet she has also gotten attentive work performed in her apartment, including a new oven, fridge, bathtub and vanity—work her lawyers attribute to her pointing out the rent-impairing violations. And with Rivers’ win in the books, Barreda of Brooklyn Legal Services is eager to test the strategy’s next phase.

Barreda’s team plans to reference the same building-wide violations—the defective fire escape, the illegal gate and door fastenings—and make the case that one of Rivers’ neighbors also should not owe rent for the time they went unfixed, since she too was at risk.

Crucially, the attorneys will argue that the court deposit is no longer necessary. Back in 1998, an appellate court ruled that tenants in the same building don’t have to make a deposit as long as one of their neighbors has already proven a rent-impairing violation existed.

Rivers is hopeful. “I am happy if they can use it, because these buildings have a lot of violations, and they’re not fixing it, but they’re demanding rent,” she said. “And I didn’t know that we didn’t have to pay rent because of this rent-impairing of the building.”

Adi Talwar

Rakia O’Bryant, third from right, after a tenant meeting with her neighbors in March.At 1402-08 Sterling Place in Crown Heights, the prospect of raising rent-impairing violations on behalf of more tenants is further off. Judge Cohen has ordered the Elliots and Ms. June to go to trial first, since their landlord is disputing how long the violations across their buildings were actually open.

But their rent strike is ongoing in the meantime, and neighbors like Rakia O’Bryant, a special education teacher with two young children, feel resolved to continue. “The longer they take to make repairs, the longer we will be on rent strike,” she said.

For O’Bryant, the issues inside her own apartment are more top of mind than common-area rent-impairing violations—things like broken cabinets and leaks. But as someone who is actively withholding rent, the intent of the law makes sense.

“Just like they want their money, we want things to be fixed,” she said. “I don’t know how else to explain that—when you go to work, you have to work in order to get paid. So do your job, and y’all will get paid.”