Advocates say the findings add new urgency to the state’s efforts to transition its energy sources away from fossil fuels, and as environmental groups renew calls for state lawmakers to pass legislation that would ban gas hookups in new construction statewide.

Jeanmarie Evelly

Nearly 19 percent of childhood asthma cases across New York can be attributed to the use of gas stoves in homes, a new analysis estimates—what advocates say adds urgency to the state’s efforts to transition its energy sources away from fossil fuels, and as environmental groups renew calls for a statewide ban on gas hookups in new construction this year.

The findings, published late last month in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, used an epidemiological tool called the Population Attributable Fraction to calculate the percentage of childhood asthma cases that can be attributed to gas exposure, based on American Housing Survey data and a meta-analysis of previous health studies about the risks posed to kids by gas stoves.

The analysis concludes that 18.8 percent of New York’s childhood asthma cases “could be theoretically prevented if gas stove use was not present.” Nationwide, 12.7 percent of childhood asthma—the equivalent of 650,000 kids across the country—is driven by gas exposure, according to the report.

The implications of the analysis’ findings for local policy makers are “stunning,” said Raya Salter, executive director of the Energy Justice Law and Policy Center and a member of the state’s Climate Action Council, the group tasked with creating a roadmap for how New York will meet the benchmarks set under its 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA).

The findings, she said, “increases the pressure” on New York to phase out the use of gas for heating and cooking in homes and to shut down fossil fuel-burning power plants, and “further substantiates the need to do it quicker and faster.”

“This should be like a real death knell to fossil fuels in that process,” said Salter. “We know that gas is harming folks. It’s harming kids. It’s—I hate to say it—killing us in our own homes.”

In New York City, 9 percent of public school students—about 60,000 children—have active asthma, a 2021 Health Department briefing found, with an even higher percentage in The Bronx (at 12 percent). Nearly 73 percent of homes in the five boroughs use piped gas for cooking fuel, the U.S. Census’ American Housing Survey shows. Across the state, 84 percent of low-income households rely on fossil fuels for energy, well above the national average of 54 percent, a separate study found last year.

Both New York city and state lawmakers have grappled in recent years over how, and how quickly, to transition the state’s energy sector to more renewable sources. Last year, the city passed legislation that will phase in limits on the use of fossil fuels in newly constructed buildings starting this year, and require all new buildings to be fully electric by 2027.

Similar legislation at the state level, which would have banned gas hookups in new construction statewide, failed to pass in Albany last year. But environmental advocates hope to see the All-Electric Buildings Act make it across the finish line in 2023, which would make it the first state to pass such a measure.

Critics of the gas ban bill, however, claim the legislation would increase costs for customers and could affect reliability of service. Many utility provides have called for the state to adopt a hybrid energy model instead.

“No single form of energy will be sufficient to achieve the goals of the Climate Act in a safe and responsible way,” Randy Rucinski, deputy general counsel and chief regulatory counsel for the National Fuel Gas Distribution Corporation testified at a public hearing on the legislation in May.

The utility company serves some 700,000 customers in Western New York, he said, and the bill “could have serious repercussions in terms of energy reliability, resiliency and affordability for New Yorkers.”

Liz Donovan

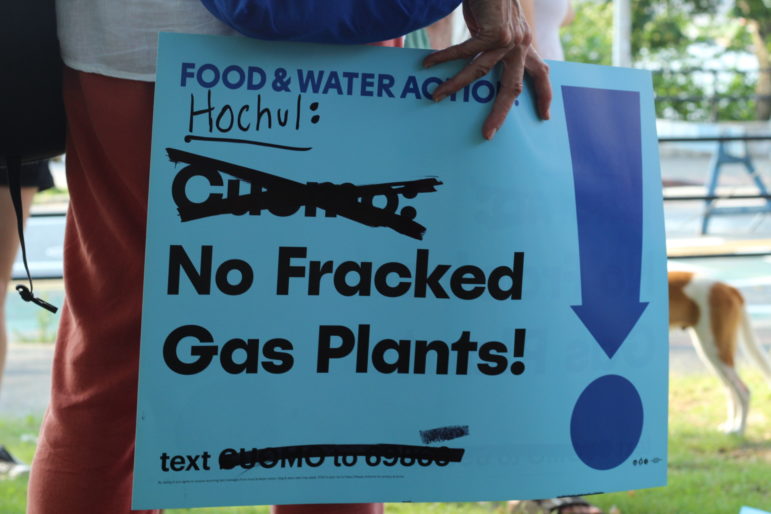

A protestor holds a sign at a rally opposing a power plant proposal in Astoria last year.Environmental groups, however, counter that the costs of fossil fuel energy sources are volatile themselves, pointing to soaring utility bills for New Yorkers in recent months, in addition to the health risks—and related expenses—associated with their use.

“We also know that the economic costs of pediatric asthma are extremely high,” said Talor Gruenwald, a research associate at Rewiring America, a nonprofit that promotes electric energy and one of the authors of the gas stoves analysis, which was produced by the clean energy advocacy organization RMI, Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the University of Sydney.

Households can help mitigate the harm of gas stoves by opening a window or using their appliance’s ventilation hood, but the most effective way is to switch over to using an electric stove instead, Gruenwald said.

“There are individual benefits…and also broader community benefits that we can realize from switching to electric cooking,” he said. The recently passed federal Inflation Reduction Act, he added, includes billions of dollars that will fund rebates and credits to help consumers purchase more energy-efficient appliances.

The Climate Action Council’s recently released scoping plan also makes the case for a swifter move to electrification, said Salter. The plan, published last month after three years of hearings and meetings between the Council’s members, is intended to be provide guidelines for lawmakers and state agencies as they seek to craft specific policies for how New York will reach the CLCPA’s mandate of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent by 2030.

The plan calls for the state to convert the “vast majority” of gas customers to all-electric by 2050. It estimates that decarbonizing New York would result in health benefits to the equivalent of $50 to $110 billion over the next 30 years, a number that Salter said did not consider the impact of reducing the use of nitrogen dioxide—a common byproduct of gas stoves—because the related data wasn’t available then. The new report’s findings indicate that the benefits of eliminating gas fuel in homes are likely much higher, “by an order of magnitude,” she said.

“The status quo is not the cost effective solution. It’s not the affordable solution. It’s not healthy solution,” Salter said.