Among immigrant-headed households with children, 52 percent experienced rent burden in 2021, a new study describes, compared to 48 percent of households with kids headed by native-born New Yorkers. Non-citizen immigrants specifically saw the highest rates of rent burdened households: 55 percent for those without children and 59 percent of those with children.

Lea la versión en español aquí.

The pandemic has disproportionately affected New York’s communities of color and immigrants in several respects: they lost more jobs and died at a higher rate from COVID-19.

They were also more likely to face housing insecurity compared to white residents in 2021, a new data analysis shows, as rent prices have surged across the city and inflation has risen higher than many people’s incomes.

More than a million, or 1,122,000 New York City households, were rent burdened last year, meaning that more than 30 percent of their income goes exclusively to the rent, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey analyzed by Citizens’ Committee for Children (editor’s note: CCC is a City Limits funder). Immigrant New Yorkers, especially those who are not citizens, are more likely to experience this financial burden, the analysis found.

Among immigrant-headed households with children, 52 percent experienced rent burden in 2021, CCC’s study describes, compared to 48 percent of households with kids headed by native-born New Yorkers. Non-citizen immigrants specifically saw the highest rates of rent burdened households: 55 percent for those without children and 59 percent of those with children.

Non-citizen immigrant households also had the highest rates of overcrowded housing in New York City across all major race groups, with Latinos facing the highest rates of overcrowding, CCC states in the analysis.

“In addition to lack of income to afford New York City’s high rents, immigrants face language barriers, lack of credit history, lack of familiarity with our housing system, and lack of access to affordable housing options,” said Lucy Block, senior research and data associate for the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD). “Because of these realities, immigrants are more likely to live in unsafe and/or overcrowded housing, which led to fast COVID spread in dense immigrant neighborhoods early in the pandemic and the recent tragedies of basement flooding deaths.”

Since the state’s pandemic moratorium on evictions expired in January, a cascade of evictions has poured into the city’s housing courts, in which there was already a long line of pending cases.

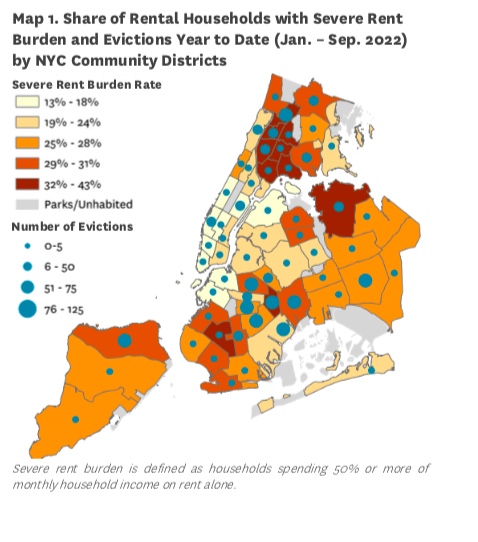

Neighborhoods with the largest proportion of “severely” rent burdened households in 2021 (in which rent constitutes 50 percent or more of the total household income) overlap with areas where evictions are being filed this year, pointing to “a relationship between housing unaffordability and potential homelessness,” according to the analysis by CCC.

“The pandemic only exacerbated the housing crisis,” Alice Bufkin, CCC’s associate executive director for policy and advocacy, said over the phone. “Overcrowded households, rent burdened tenants and higher rent prices, all of that has contributed to the crisis we’re seeing now.”

A January 2022 report by ANHD warned about those disparities, highlighting that racial and ethnic groups who were behind on rent during the pandemic “mirror the racialized patterns of eviction cases.” Of the population that was behind on rent when the moratorium ended at the start of the year, 35 percent were Latino residents and 35 percent were Black residents, the report found. When added together, communities of color constituted 85 percent of New Yorkers who were behind on their rent at the time, despite accounting for just 44 percent of the general population.

Last month, news reports found that fewer than 10 percent of city tenants facing eviction in September had access to an attorney in Housing Court, despite the city’s 2017 Right to Counsel law entitling free representation for renters whose income threshold is below 200 percent of the federal poverty line.

The situation becomes even more dire for immigrants at risk of eviction, according to Block, since there are not many Right to Counsel lawyers who speak Spanish, let alone Bangla, Mandarin, Arabic, Haitian Creole, and the hundreds of other languages spoken by New Yorkers.

“Immigrants are more likely to face language barriers that make it hard to know about and receive legal representation they may be entitled to through Right to Counsel, when there are not even enough lawyers to represent tenants who speak English,” Block said.

Demographic information about who does and doesn’t have representation in court is not available, Block said, though representation rates by zip code, mapped last month by news site THE CITY, may give some insights. “You can see very low representation rates in Elmhurst, Corona, Jackson Heights, Astoria, Jamaica, Southeast Queens, and Inwood, all of which have very large immigrant populations,” she added.

Data provided by the state Office of Court Administration to the Housing Data Coalition (HDC) and mapped by the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition shows that in two of the zip codes with some of the highest evictions filings per 1,000 units since the pandemic began (10468 and 10453, both in The Bronx), more than 80 percent of the population is Latino and 40 percent is foreign-born.

Advocates are pushing for policies at both the local and state level to ease the impact of the housing crisis on immigrant communities. For example, after New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a package of reforms this week intended to help unhoused New Yorkers secure permanent housing through the City Family Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement (CityFHEPS) rental subsidy program, housing and immigration advocates turned out to ask for further inclusion of undocumented people and asylum seekers, who are not currently eligible for the rental assistance vouchers.

“While this slate of reforms is necessary and long overdue, it is only a first step,” said New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC) Murad Awawdeh in a statement. “The City must also make these programs, including a further expansion of the CityFEPS program, available to all New Yorkers regardless of immigration status to give asylum seekers and others a real chance at building new lives and fully integrating into our communities.”

The other step that should be taken at the local level, Bufkin says, is to end the rule that requires applicants to have spent at least 90 days in shelter to be eligible forCityFHEPS.

At the state level, these organizations advocate for an increase in funding for ERAP, the state’s pandemic rental assistance program, to address over 100,000 pending applications, and press for the approval of tenant-friendly bills, such as the implementation of the Housing Access Voucher Program, or HAVP, which would provide rental assistance for individuals and families across the state who are homeless or who face an imminent loss of housing.

They are also calling for the passage of legislation that would recalculate the state’s shelter allowances to match 100 percent of the Fair Market Rent Standard (A8900A); Another bill that would increase cash assistance grants to account for inflation (S9513); and a third that would require the state to annually adjust the minimum wage by a percentage based on inflation (S3062C).