Residential rezonings, including one approved this summer for Edgemere, are poised to bring thousands of new apartments to the Rockaways over the next decade, but just a single hospital has served the peninsula since 2012. A new task force is being asked to create a roadmap for expanding local healthcare services, including a facility that offers trauma care.

Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office

Mayor Eric Adams and other elected officials cutting the ribbon on a new housing development on

At a ribbon cutting for an affordable housing development in Far Rockaway in August, Mayor Eric Adams lauded the project—which built 224 apartments on vacant, city-owned land along Beach 21st Street—as a key success story of the city’s 2017 20-block rezoning of the neighborhood, which housing officials say has paved the way for some 2,000 income-restricted apartments so far.

Another rezoning, approved by the City Council in July, could bring up to 1,200 new apartments to nearby Edgemere, what officials say will help fill the city’s desperate need for affordable housing. It’s one of several projects with the potential to transform swaths of the Rockaway peninsula, where the population grew by nearly 8 percent between 2010 and 2020, census data shows.

One thing that hasn’t grown: the number of hospitals. Since 2012, when Peninsula Hospital Center closed its doors, Rockaway has had just one full-service hospital facility, to the dismay of residents and elected officials. But with the expected influx of new local development, that should change, they argue. A petition calling for a trauma care center—a designation the peninsula’s lone St. John’s Episcopal Hospital doesn’t have—earned more than 800 signatures in the last week.

“They should have built another trauma hospital instead of more apartments,” one signatory wrote.

The neighborhood’s City Councilmember Selvena N. Brooks-Powers has convened a task force to explore options for expanding heath care on the peninsula, including the possibility of a new trauma hospital in Far Rockaway. The Taskforce on Trauma and Healthcare Access, as it’s called, will beging meeting next month, and includes local residents, members of nearby community groups as well as health care experts like NYC Health + Hospitals President Mitchell Katz.

It was one of the commitments City Hall made in negotiations over the Edgemere rezoning plan, which drew opposition from local residents, in part over the lack of the area’s healthcare infrastructure (the administration also pledged to open a community health center in the district as part of the deal).

“We are geographically isolated. And every moment counts if you’re having a stroke, if you are at risk of dying from drowning,” Brooks-Powers told City Limits in an interview Monday, referencing the death of two swimmers in separate incidents at Rockaway Beach this summer.

The issue of health care access for the peninsula is personal, said the councilmember, who was an employee of Peninsula Hospital when it shuttered in 2012. She has a young nephew who has a gastronomy tube and lives on the same block as St. John’s Hospital, but it doesn’t offer pediatric care. “When he is in crisis mode, his parents have to take him to Long Island to get the treatment that he needs,” she said.

The lack of more local facilities became particularly stark during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Brooks-Powers added, with Far Rockaway among the neighborhoods with one of the highest death rates in the city. “It’s been a constant and consistent request and cry for help from the community.”

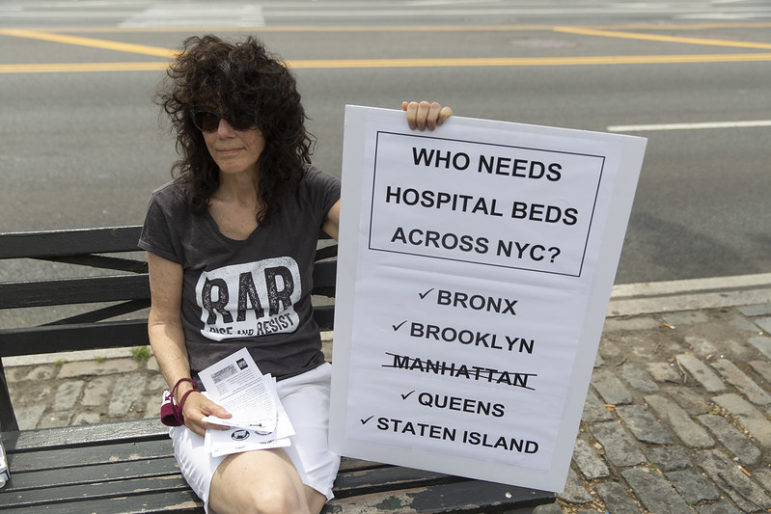

Beyond the peninsula, hospital capacity has shrunk significantly across New York in the last few decades, as dozens of facilities closed, merged or downsized, some of them at the behest of a state commission convened by former Gov. Pataki to rein in medical spending. Today, Queens has the fewest hospital beds proportionate to population out of the five boroughs, with just 1.5 for every 1,000 residents, a 2020 report from the Community Service Society found (CSS is a City Limits funder). “The most impacted communities have been Black and brown,” Brooks-Powers said.

John McCarten/NYC Council

A rally to save Brooklyn’s Kingsbrook Hospital, which shuttered much of its services in 2021.

The decline in capacity has forced city agencies and officials to grapple over how health care infrastructure should play into land use decisions, as Mayor Adams looks to address the local housing crisis by turning New York into a “city of yes.” Legislation passed in Albany last year will now require hospital systems that want to shutter or merge to assess what impact the change will have on the surrounding community. More locally, Councilmember Lynn Schulman, who also represents Queens, wants hospital capacity to be one of the considerations required by the city’s land use approval process.

The new Healthcare Taskforce, which will hold it’s first meeting on Nov. 19, will be charged with creating a “roadmap” for expanding healthcare facilities in the Rockaways, considering things like costs, location and the type of care best needed. Brooks-Powers hopes that will result a trauma center for the neighborhood, either in a new hospital or by expanding the services offered at St. John’s.

“When I first got elected, I was extremely disappointed in some of the conversations that I had, you know, ‘You’re never going to get a trauma hospital in Rockaway,’ or ‘There’s no money in trauma hospitals,'” she said. “That’s unacceptable. We’re talking about lives.”

3 thoughts on “In Wake of Rezonings, Renewed Call for More Health Facilities on Hospital-Starved Rockaway Peninsula”

The real question is why all the affordable units were dumped into the democrats district instead of being spread evenly between both districts on the peninsula.

A classic pandemic after so many decades. I’m so lucky that everyone made it through.

So great