Advocates want the city to take a more proactive approach to lead paint inspections and enforcement, saying the current system contains loopholes that allow property owners to skirt the rules. Their push comes as the Health Department considers lowering the childhood lead-level threshold that would automatically trigger an investigation.

Adi Talwar

New York City banned the use of lead-based paint in residential buildings in 1960—an effort to prevent the health effects identified with lead poisoning, which can cause significant cognitive and behavioral health problems in children.

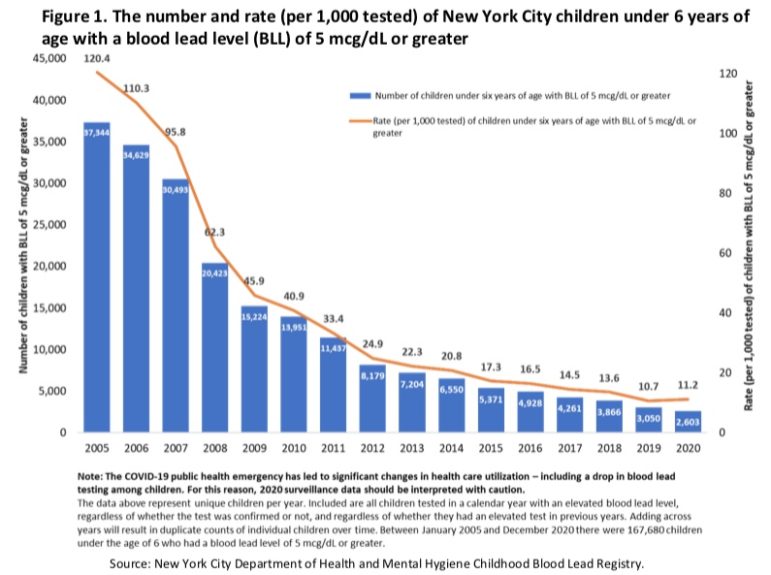

But more than 60 years later, thousands of city kids still test positive for lead exposure annually. In 2020, the most recent year for which data is available, 2,603 of New York City children under the age of 6 tested for elevated blood lead levels, what experts say is likely an under-count considering the impact of the pandemic on testing that year.

“[T]he reality is that we are still seeing children poisoned every year,” Manhattan City Councilmember Gale Brewer wrote in a letter last week to the various city agencies that oversee lead-based paint regulations.

She’s one of several public figures and environmental advocates calling on the city to take a more proactive approach to lead paint inspections and enforcement, saying the current system contains loopholes that allow property owners to skirt the rules too easily.

Their push comes as the city’s Health Department considers lowering the childhood lead-level threshold that would automatically trigger an investigation by the city from 5 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL) to 3.5 mcg/dL. The proposed new level—which matches the CDC’s current guidelines—will allow health officials to identify potential lead poisoning cases earlier, advocates say.

It will also mean an uptick in the number of children testing positive for lead exposure and in need of intervention, making it even more important that the city shore up its testing, inspection and enforcement processes now.

“It’s best to kind of get ahead of that,” said Lonnie Portis, an environmental policy and advocacy coordinator at WE ACT for Environmental Justice. The group is a member of the New York City Coalition to End Lead Poisoning (NYCCELP) which is pushing for a specific list of changes for the city to undertake in how it regulates lead paint risks.

Under current city rules, landlords with properties built prior to 1960 are required each year to inspect any apartment that’s home to children aged 5 or younger (or where any young children spend at least 10 hours a week). They then must correct any lead hazards they identify, which can include things like peeling or damaged lead paint, lead paint on window sills or other surfaces that kids can reach or on doors or windows that touch together.

But advocates say those requirements are often left to landlords to comply with voluntarily. Though the Department of Housing, Preservation and and Development (HPD) does conduct regular audits at buildings it or the Health Department identifies as at risk for lead hazards, it did so at just more than 700 properties in Fiscal Year 2021 (that same year, HPD issued 9,489 violations related to lead paint, city data shows).

The NYCCELP is pushing for legislation in the City Council that would strengthen the city’s oversight rules, including a bill introduced by Councilmember Diana Ayala that would require property owners who’ve received a lead violation to produce their self-inspection records and proof of abatement measures to the city. She also introduced another bill that would set a hard deadline, July of 2023, for all buildings older than 1960 to remove any “lead-based paint on friction surfaces on doors and windows”—abatement work that’s currently only required when an apartment sees tenant turnover.

Additional bills in the same legislative package would prohibit peeling lead paint in the common areas of buildings where young children reside, not just in individual units where kids live, while another would require the city to report any objections it receives to lead abatement orders from property owners and NYCHA.

The city should “be serious about enforcement and corrective action,” Brewer wrote in her letter to the administration last week. “There must be swift action against landlords who do not comply, and support for owners who want to comply but cannot.”

In response to questions from City Limits, representatives for HPD and the Department of Health said they’re reviewing the councilmember’s letter and requests.

“HPD is committed to protecting children from the hazards of lead-based paint and working to ensure safe and healthy homes,” agency spokesperson William Fowler said in an email. “In addition to checking for lead-based paint hazards at every inspection where a child under six spends 10 or more hours a week in the unit, New York City has reduced the threshold for the amount of lead in paint that triggers remediation and abatement to be the lowest of any major US city.”

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene pointed to the drastic reduction in city kids with elevated blood lead levels over the last two decades. From 2005 to 2020, the number of children with levels at or higher than 5 mcg/dL (the current threshold that triggers an inspection) dropped by 93 percent, from 37,344 to just over 2,600.

But advocates say that number should be zero. In addition to legislative action, they want the city to invest more funds and resources in inspection and enforcement, public awareness campaigns that encourage more parents to seek out testing, as well as prevention and early intervention programs. They also want the city to more aggressively identify and replace water service lines contaminated with lead, another main source of childhood exposure.

“There’s just so much that could just be done by the city and by law, to just kind of really just get rid of this problem altogether,” said Portis.

Those impacted by lead exposure are disproportionately low-income children and children of color, he and other advocates note. Of the 2,603 New York City children under 6 who tested for elevated levels in 2020, 65 percent were from high-poverty neighborhoods. Asian, Black and Latino kids accounted for 78 percent of the 1,505 newly identified cases that year, according to city data.

NYCCELP’s members want the City Council to hold an oversight hearing on the issue and package of related bills as a first step.

“To hear about what is going on, why there’s still this disparity, what the city agencies are doing, how they’re preparing, we really need to be able to drill down on some of these,” Portis said.