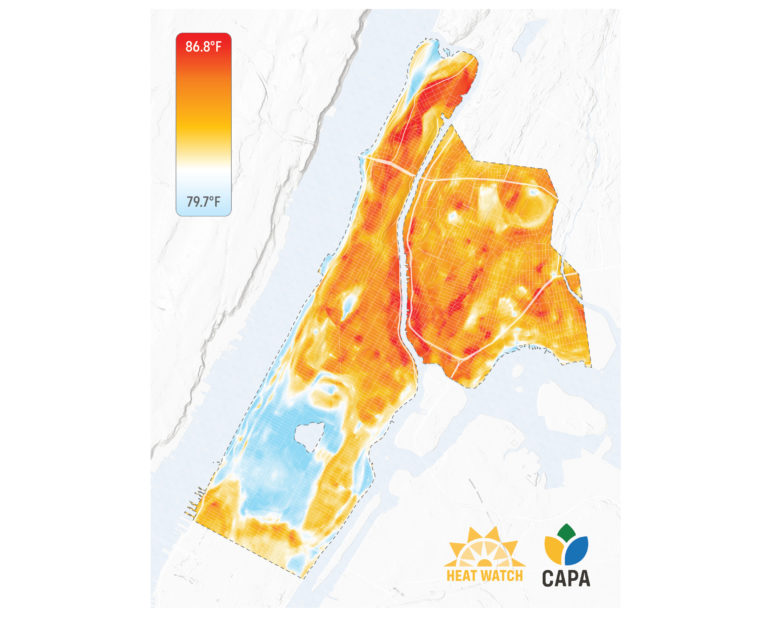

For instance, during one data collection, neighborhoods surrounding Central Park measured between 80 and 82 degrees, while parts of The Bronx and upper Manhattan were between 88 and 89 degrees at the same time.

CAPA Strategies

Researchers at Columbia’s Climate School worked with volunteers this summer to document neighborhood temperatures.Researchers at Columbia’s Climate School and local organizers recently revealed the results of a months-long effort to collect street-level data of temperatures in New York City during the summer—reinforcing earlier findings that certain areas suffer disproportionately from hot weather.

The goal, according to researchers, was to document how different neighborhoods are impacted by the urban heat island effect—clusters of the city where average temperatures are higher due to infrastructure, lack of green space and other factors. Researchers collected data this summer across Manhattan north of 59th Street, and parts of The Bronx. (An attempt to collect data in Brooklyn was canceled due to lack of volunteers.)

The results showed that Inwood, Washington Heights and the South Bronx—neighborhoods populated predominantly by people of color and of low-income individuals—had higher temperatures in a given day and time than in more wealthy Manhattan neighborhoods.

For instance, during a data collection from 3 to 4 p.m., neighborhoods surrounding Central Park measured between 80 and 82 degrees, while parts of The Bronx and upper Manhattan were between 88 and 89 degrees at the same time. When temperatures dropped across the city in the evening hours, they hovered about 4 degrees higher in those hotter neighborhoods, the data shows.

The areas with higher temperatures match areas with less access to air conditioning and other resources, the researchers said.

The findings are similar to previous mappings of the city’s heat islands, but the nature of the research allowed for a more accurate presentation of how temperatures are felt in neighborhoods across the city, the project’s organizers say.

Lead researcher Liv Yoon explained that previous heat mapping research used satellite imaging to capture average temperatures on a given block. Her method instead relied on sensors and boot-leather data collection techniques to track real-time temperature and humidity at the street level. This resulted in data that more closely matches conditions felt by the community than what satellite imaging could capture.

Liz Donovan

Ashley Fontanilla of South Bronx Unite participates in a heat mapping project.

“When you look on Google Maps and see that there are parks throughout these areas, what we don’t know from those maps are that some of these parks are just slabs of concrete with a swing set with no trees,” said Yoon.

On data collection days, teams of volunteers would drive along one of nine routes in the project area with a sensor attached to their vehicle. They would complete the route at three predesignated times to show how the humidity and temperature varied throughout the day.

Yoon and her colleague, NASA scientist Christian Braneon, involved community members in their data collection—a method Yoon said helped engage residents by allowing them to actively document how they experience summer heat in their neighborhoods.

“We say that people cannot be what they don’t see,” said Melissa Barber, co-founder of South Bronx Unite, one of the groups that participated in the project. A key takeaway, she said, is the fact that the study was conceived and led by people of color, from the researchers to the organizers to the volunteer data collectors. “They were able to see people who look like them, heading this type of research, people from their community, who really were passionate about issues in their community.”

The study was completed in partnership with Columbia Climate School and data analytics group CAPA Strategies, and was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It’s part of a national effort to collect data in at least three dozen cities.

Yoon also noted that she was surprised to find hotter pockets along a study route in the Upper East Side, where in the morning the temperature was about as high as the temperature collected in the South Bronx. Further analysis of the overlapping disparities in the neighborhood may show that this area, which has higher average income than the other neighborhoods with such hot spots, is better able to manage the effects of heat, Yoon noted.

“These hot spots in the UES are likely less threatening to the population there given resources and access to air conditioning, more access to health care,” she said.

Yoon said she expects their findings will be presented in an online story map available in English and Spanish this spring, and hopes the data will inform a more equitable approach to climate change mitigation. The mapping will include other markers of inequality, including lack of access to healthcare and air conditioning. It’ll also identify overlaps with redlined communities—neighborhoods historically deemed risky for mortgage lending and predominantly made up of people of color.

“Connecting the dots…can emphasize that the way to tackle this issue is to go beyond just temperature and humidity,” Yoon told City Limits. “Adaptation measures like A/C access and cooling centers are urgent and vital, but it can’t stop there. We need to also think about equitable reform more broadly.”

Solutions to the heat island effect, like adding vegetation and shade or painting rooftops a lighter, reflective color, should be prioritized in communities marginalized by race and class, Yoon said.

A city report released last summer found that more than 100 New York City residents died from heat stress between 2010 and 2020, and 43 percent of those individuals were Black. Previous research has also found that communities of color tend to lack access to natural shade, which can reduce temperatures by as much as 20 to 45 degrees, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Another report by American Forests, also released this past summer, found that trees in New York and other cities across the country were more prominent in areas where higher-income white residents lived than in neighborhoods home to people of color. New York would need to add 1.5 million trees to provide equitable cover across the city, the report said.

“Climate change is not just about temperature, humidity and polar bears,” said Yoon. “It’s a sociopolitical issue. Racist policies matter in how climate change manifests in people’s lives. This is a social crisis, and we need to be thinking more broadly and holistically.”

Liz Donovan is a Report for America corps member.

2 thoughts on “NYC Heat Mapping Study Finds Higher Temps in Lower-Income Neighborhoods”

This is a great study. Thank you!

I have lived in Inwood for 28 years and always felt that coming back uptown on a hot summer night, that you can feel it is usually about 5 degrees cooler than downtown. But this temperature study proves otherwise.

I know well we do not have enough street trees up here on almost every block, in fact, my own building has just 1 tree pit in front of it, but every time the city plants one, our neighbors with dogs allow their dogs to pee & poop in the pit, thereby killing it within about a year. We have had at least 5 new trees that all eventually die. Even after a neighbor in my bldg & I fashioned a rudimentary stake & rope tree surround that eventually was crushed.

Our bldg is also on the east side of the street which does not get good morning or late afternoon sun, only noon sun, and so along with 3-4 other pits on our side, they all keep dying. It’s very disappointing to see. The west side of our street has trees & a garden that are all thriving bc they are all in front of or next to co-op bldgs, and the trees have iron surrounds & get watered. The economic disparity plays out right on my 1 block in Inwood as the prices for co-ops have skyrocketed over these 28 years, bringing in very well-off people, in comparison to the rest of Inwood. .

I only wish we could first get city funding to get our building roofs painted white, offering those jobs to local un- or underemployed young men & women.

Then I feel that this endeavor to plant & care for more street trees would need to get city help to build basic tree surrounds, and then have mulch delivered every fall, along with a good hose and a couple of basic gardening tools for each block or building that has a tree steward that we could identify at the community meetings Inwood to teach them about our higher temperatures up here & how caring for trees can mitigate that problem.

Then engage the most interested on every block, including a few shopkeepers on the 2-4 main shopping streets up here (Dyckman St & W 207th St, then fewer on Broadway & 10th Ave/Nagle Avenue, & even Sherman Ave) to work caring for our costly trees that are such a valuable resource.

Thank you for reading about my concerns & ideas for building a better, more equitable, natural & cooler Inwood. I am hoping that the Columbia climate students might partner with this community to test this idea.

As a lover of trees and Columbia alumna, I thank you for doing this study and confirming what many of us have been feeling. Last summer, our organization did a project to plant gardens throughout Washington Heights, and it was heartbreaking to see how many street tree pits were empty while the community dealt with sweltering temperatures. We plan to return this year to plant trees, but more is needed. Our organization would be thrilled to partner with community groups, governments or property owners to help bring more green to these historically underserved communities. http://www.nyctreepitservices.com