The chair of the City Council’s welfare committee says New York City is squandering a ‘once-in-a-generation’ opportunity to address its homelessness crisis, despite an executive budget that would boost Department of Social Services (DSS) funding by nearly $1.2 billion.

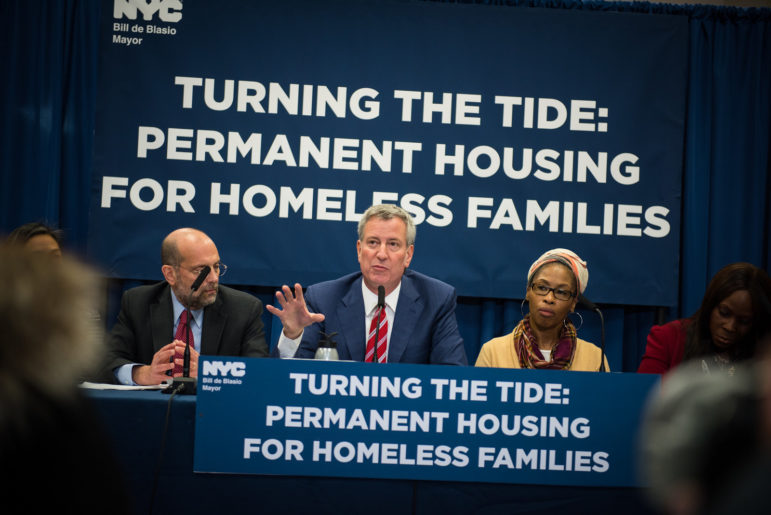

Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office

The mayor at a homelessness-related press conference earlier in his tenure.The chair of the City Council’s welfare committee says New York City is squandering a “once-in-a-generation” opportunity to address its homelessness crisis, despite an executive budget that would boost Department of Social Services (DSS) funding by nearly $1.2 billion.

During a hearing Monday, Brooklyn Councilmember Stephen Levin said Mayor Bill de Blasio’s $98.6 billion spending proposal does not do enough to ensure housing for the tens of thousands of New Yorkers who experience homelessness — including 15,587 children in shelters run by the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), according to the most recent city census report.

Levin specifically grilled DSS Commissioner Steven Banks on the agency’s budget priorities and opposition to a measure raising the value of rent subsidies that are intended to help homeless families move into permanent housing but typically go unused.

“The recent influx of federal pandemic aid is a significant, once-in-a-generation opportunity for the city to make meaningful and lasting changes to policies that we have so long sought to change but found ourselves limited in achieving because we did not have the funding,” Levin said. “We likely won’t get another chance to do this again.”

The executive budget would allocate just over $11 billion, or nearly 12 percent of total spending, to DSS, which includes DHS and the Human Resources Administration. In spite of the cash infusion, DHS would see its budget trimmed by about $661 million in the 2022 fiscal year, which starts in July, after federal emergency funds expire.

The proposed budget does not, however, increase funding for the rental subsidy known as CityFHEPS, a program that pays for a year of rent for families in city homeless shelters who can find a landlord willing to accept the below-market rate of a voucher. A measure introduced by Levin and sponsored by 39 other councilmembers would raise the value of the voucher to the Fair Market Rent established by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and used to set the value of the federal Section 8 program.

Councilmembers have discussed boosting the voucher value via the budget rather than a legislative process that lacks support from the mayor. Council Speaker Corey Johnson has not yet brought the bill to a floor vote, despite backing from the majority of the council, as well as advocates and the landlord lobby.

In New York City, Section 8 is pegged at $1,945 for a one-bedroom apartment or $2,217 for a two-bedroom. In contrast, the CityFHEPS vouchers are capped at $1,265 per month for a single adult and $1,580 for a family of three or four. Advocates say the voucher value trails the market rate in every single New York City neighborhood.

“The CityFHEPS rate is a major source of frustration for me,” Levin told Banks. “It’s not sustainable. We have to increase this voucher to Fair Market Rent or Section 8 levels. There’s a moral issue here … we can’t just give people vouchers that are really ineffective.”

Banks said he, too, would like to see the voucher value rise, but balked at the city hiking the rate without New York state increasing the value of its parallel FHEPS program, which is pegged at 85 percent of Fair Market Rent. A unilateral increase could lead to the city paying hundreds of millions of dollars more, with the state further abdicating its responsibility for city homeless services and rental subsidies, Banks said

“There’s a danger if the city increases alone without a state FHEPS increase,” he said. “It doesn’t take any great analysis to say that if the state FHEPS benefit level is lower than the CityFHEPS, then landlords will accept the CityFHEPS and not the state benefits level.”

That would be the latest development in the state’s long disinvestment in New York City homeless services, he said.

State Sen. Brian Kavanagh last week introduced legislation to increase the state voucher value in cities with 5 million or more residents — i.e New York City.

Banks also resisted the notion that the city establish the voucher value increase using the cash from the federal government. Those funds won’t be there next year, he said.

“A Fair Market Rent increase is permanent; stimulus money is one time,” Banks said. “It’s like if you and I went out and said, ‘I just got $1 million, I’ll take on a $1 million-a-month obligation and that $1 million was only one time.’”

After the hearing, Levin said the city could indeed use the federal money to establish needed programs, like the voucher value hike, that future lawmakers are unlikely to repeal. The city will have cash to continue the program through rebounding property tax revenue plus cost savings accrued after more families move out of shelters, he said. The family shelter organization Win estimates that the CityFHEPS voucher increase will save the city $187 million in the first five years, with up to 2,700 families moving out of pricey shelters.

The proposed budget does boost funding to tackle another obstacle facing voucher-holders: source of income discrimination. Banks said the city will hire more attorneys and staff to investigate and crack down on landlords who illegally reject prospective tenants with rent subsidies. Landlords frequently ignore inquiries once they learn a renter has a CityFHEPS voucher.

Banks said DSS received 482 source of income discrimination complaints last year, including 213 that named specific landlords or apartments. The agency managed to address 53 of the cases, getting the landlord to rent the unit in 29 instances, while referring 24 other cases for enforcement and further investigation, known as testing, he said.

A host of other needs

The voucher issue isn’t the only funding gap that worried city lawmakers Monday.

Councilmember Daniel Dromm, chair of the finance committee, said he sees a “concerning amount of insufficient funding in key safety net areas,” namely access to public assistance and food assistance. The Council urged the de Blasio administration to increase funding for outreach and access services in its preliminary budget response last month after the number of qualifying New Yorkers surged as a result of the pandemic and corresponding economic crisis. The executive budget would add 103 new staff members to determine eligibility and administer the program at a total of $13.7 million.

Banks said that DSS fostered access by receiving permission to allow benefit recipients to apply, renew or attend meetings by phone. In addition, the agency reassigned 1,000 workers to handle frontline entitlement assistance, with Banks telling Dromm those employees will remain in those roles.

“We’re not going to re-assign the assigned staff until we can make sure we’re covering our cash and SNAP benefit delivery,” he said.

He suggested the agency will work with the Office of Management and Budget to hire 1,000 new employees.

The council has also encouraged the city to continue its pandemic policy of placing single adults in private one- or two-bed hotel rooms to prevent the spread of COVID-19, a program the city has dubbed “de-densifying,” at a cost of $568 million. The Federal Emergency Management Administration reimbursed the city for most of the hotel room fees, as well as so-called “stabilization beds” for people moving directly from outdoor public places into shelters.

Banks said the city will continue the policy so long as public health experts recommend limiting the number of people inside crowded congregate shelters, where dozens of adults can share barracks-style rooms. The initiative will no doubt remain important: Just 5,000 homeless shelter residents have so far been vaccinated against COVID-19, Banks said.

When pressed by Dromm Monday, Banks said he expects FEMA will continue funding the private room initiative, though he left the duration of the policy up to the federal government.

“We are now dealing with an administration that believes that science is important and so we have a huge degree of confidence we will work with the federal government in terms of the continued need for these kinds of services for as long as, frankly, FEMA determines that it’s needed,” he said.

In addition, Banks said the city remains on track to open 1,000 “low-barrier” beds for New Yorkers who live in public places. So-called safe haven, stabilization and respite beds allow street homeless people to stay indoors without having to demonstrate sobriety, go through a cumbersome intake process or adhere to a curfew.

The 1,000 new low-barrier beds will bring the total to 4,000, though Banks acknowledged that permanent housing is the best way to move people off the street permanently — something homeless New Yorkers and advocates have said for years.

A role in rent relief and eviction protections

The city will also play a role in the state’s upcoming Emergency Rental Assistance Program by allocating $22 million to community-based organizations to conduct outreach and application assistance. The state’s existing eviction protections are set to expire Aug. 31, likely prompting a surge in evictions among low-income tenants who fail to access the state’s $2.4 billion ERAP fund.

He said state officials have assured the city that the ERAP program will be up and running by the end of this month. State Budget Director Robert Mujica previously described that timeline for the program, administered by the Office of Temporary Disability Assistance. OTDA did not respond to a request for comment.

“The state reports to us that the portal is expected to be open by the end of this month and we are preparing as soon as we learn what the portal link is to push that information out,” Banks said. “I would expect over the course of the summer people will begin to receive those funds.”

A spokesperson for DSS said the city only recently issued requests for proposals and has not yet awarded contracts to the nonprofits, with the program set to begin within the next three weeks.

The city will further increase funding for attorneys to represent tenants in Housing Court through its right to counsel program.

“Keeping a roof over your head is one of the core goals of this budget,” he said.