A fictional election to demonstrate how the new system will operate in 2021 and beyond.

Barring an unexpected court move or surprising legislative development, ranked-choice voting will be in place in special elections and primary elections for city offices in 2021 and thereafter.

Ranked-choice voting addresses the fact that in many New York City contests, there are are more than two—and sometimes as many as six or seven—candidates. Under the old system, that meant someone could win a Council seat or borough presidency with a relatively small share of the vote so long as they received more votes than anyone else. In the 2013 primary elections, for instance, Robert Cornegy, Chaim Deutsch, Daneek Miller, Helen Rosenthal and Paul Vallone won with less than a third of total votes, and several other candidates prevailed with less than 40 percent.

In citywide elections—for mayor, public advocate or comptroller—there was a requirement in the City Charter that the winning candidate get at least 40 percent. However, that sometimes meant holding a runoff election, which was expensive and often led to far lower turnout. In 2013 for example, 530,000 voters came out in the primary to vote for public advocate, but only 203,000 participated in the runoff between Letitia James and Daniel Squadron.

Ranked-choice voting aims to avoid both problems by letting voters designate whom they would pick if there was no clear winner in the primary and their top candidate was eliminated. Depending on how many candidates are in a race, a voter may pick up to five candidates to designate their choices should the counting move to a third, fourth or fifth round before a winner emerges.

Some critics have worried that the system could confuse voters. It is, after all, different from how we’ve voted in the past. (And the nuances can be tricky: The first version of this article, in face, muffed the details of the last round of counting.)

Now that the 2020 elections are behind us—the last one was Tuesday’s District 12 Council special election in the Bronx—the city’s Campaign Finance Board is rolling out an education campaign.

One way to understand how the system will work is to run a simulated election.

Our fake election

Say there six candidates in the Democratic primary race for mayor. We’ll go by last names only: Alyssa Al-Hasan, Beatrice Boccelli, Colin Cooney, Don Deng, Ernesto Encarnación and Frances Fidurski.

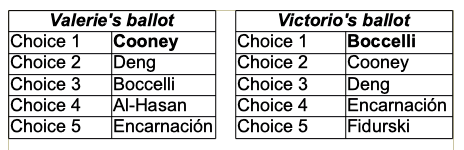

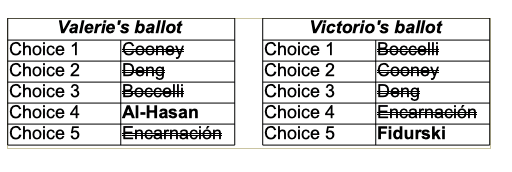

There will be hundreds of thousands of voters taking part in the primary, but we are going to focus on just two, Valerie and Victorio.

Valerie is from Queens but uses a military ballot because she’s in the Navy. Victorio lives in Harlem and votes in person on Election Day. But it doesn’t matter how they vote: Ranked-choice voting will work the same.

Here is how their ballots look after they have filled them out:

The counting begins: Round 1

After the polls close on Election Night and all the mail-in ballots get counted, here’s how the results look:

| Round 1 Results | |

| Candidate | Vote Share |

| Al-Hasan | 29% |

| Boccelli | 6% |

| Cooney | 5% |

| Deng | 19% |

| Encarnación | 18% |

| Fidurski | 23% |

The election could end here if someone has a majority. But no one has. So, the lowest-ranking candidate—Cooney—is eliminated.

The field narrows: Round 2

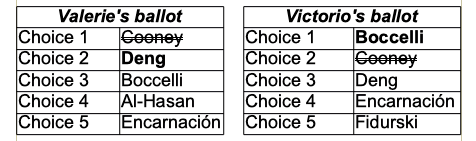

Once Cooney is eliminated, all the voters who picked Cooney as their number one choice have their ballots re-examined and their second choice is taken.

Valerie voted for Cooney first. So now, Valerie’s second choice counts: Deng. Victorio’s first pick, Boccelli, is still in the race, so his vote still goes to Boccelli.

Once all the Cooney voters’ second-choices are counted, the tally is run again. All the other voters—those who, like Victorio, chose candidates other than Cooney as their first choice—still have their first picks counted.

These are the results:

| Round 2 Results | |

| Candidate | Vote Share |

| Al-Hasan | 33% |

| Boccelli | 7% |

| Cooney | (eliminated) |

| Deng | 16% |

| Encarnación | 21% |

| Fidurski | 23% |

What happened to generate this result? Remember that our five imaginary voters are just a sliver of the electorate; hundreds of thousands of other ballots with unique combinations of candidates are being counted. It appears that Cooney supporters split their second-choice support pretty evenly among the other candidates.

Once again, the election could end here if someone emerges with a majority. But we aren’t there yet. So, the lowest-ranking remaining candidate, Boccelli, is eliminated.

Winnowing further: Round 3

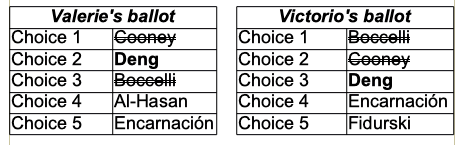

Once Boccelli is eliminated, all the voters who picked Boccelli as their number 1 have their ballots reexamined and their second choice is counted instead—unless their second choice was Cooney, who has also been eliminated.

Valerie’s second choice, Deng, is still is the race, so her vote goes to Deng. Victorio’s first and second choices, Boccelli and Cooney, have both been eliminated, so this vote goes to his third choice, also Deng.

Voters who supported Al-Hasan, Deng, Encarnación or Fidurski as their first picks still have their votes counted for those candidates.

When the tally is run among the four remaining candidates, here are the results:

| Round 3 Results | |

| Candidate | Vote Share |

| Al-Hasan | 35% |

| Boccelli | (eliminated) |

| Cooney | (eliminated) |

| Deng | 17% |

| Encarnación | 24% |

| Fidurski | 24% |

We see that Al-Hasan and Encarcion make gains in this round. That indicates that they were both popular second or third choices among Boccelli and Cooney voters. Deng was not as popular among those voters.

Once again, the election could end here, but it still doesn’t: All three candidates are still short of a majority. So, the lowest ranking candidate, Deng, is eliminated.

And then there were three: Round 4

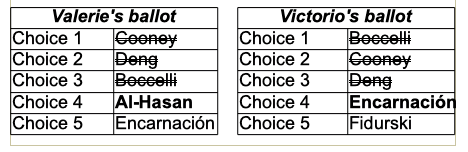

Now we are down to only three candidates: Al-Hasan, Encarnación and Fidurski.

Since three candidates—Cooney, Boccelli and Deng—are eliminated, those names are crossed over all ballots. The top-ranked viable candidate on every voter’s ballot is what counts.

In Valerie’s case, her fourth choice is what’s counted: Al-Hasan. Victorio also gets his fourth-choice counted, Encarnación.

The tally is re-run. And here are the results:

| Round 4 Results | |

| Candidate | Vote Share |

| Al-Hasan | 51% |

| Boccelli | (eliminated) |

| Cooney | (eliminated) |

| Deng | (eliminated) |

| Encarnación | 24% |

| Fidurski | 25% |

Al-Hasan finally clears 50 percent, but once the ranked-choice mechanism is engaged it proceeds until only two candidates are left. So, Encarnación is eliminated, and we move to the final round of counting.*

Round 5: Two candidates enter, one wins

In our hypothetical example, there is little suspense associated with the fifth round: Since Al-Hasan already has more than 50 percent of votes, there is no way he will not emerge from the final round without a majority. (Even if all Encarnación’s voters ranked Fidurski as their next option, Fidurski’s 25 percent + Encarnación 24 percent from Round 4 is only 49 percent, which is still less than Al-Hasan has claimed.)

In real life, it could work out differently of course. In a race that worked down to three candidates who, say, split the Round 4 vote evenly, Round 5 would be decisive.

But, let’s remain in fantasy land. Back to our example, here is how our voters’ ballots look for Round 5:

Notice that Valerie’s vote still goes to Al-Hasan, because she is still in the race. Encarnación is eliminated from her ballot but it doesn’t matter. Victorio’s vote goes to Fidurski.

And here are the final election results:

| Final (Round 5) Results | |

| Candidate | Vote Share |

| Al-Hasan | 56% |

| Boccelli | (eliminated) |

| Cooney | (eliminated) |

| Deng | (eliminated) |

| Encarnación | (eliminated) |

| Fidurski | 44% |

It appears the vast majority of people whose fourth-round votes went for Encarnación chose Fidurski next, but it doesn’t change the outcome: Al-Hasan is the Democratic mayoral nominee.

It’s just math

Note that one’s vote counts more than once. The tally is run anew in each round. Each voter’s top viable candidate gets their vote.

By ranking more than one candidate, a voter is not undermining her or his top choice: The second, third and later choices will only count if your first-choice candidate is out of the running. It’s like designating a contingent beneficiary in your will: You leave everything to dear Aunt Judith. But if Aunt Judith has already passed away by the time you move to the Cloud of Witnesses, Cousin Jeremiah gets your estate. It’s also like the depth chart for a baseball team: The “emergency catcher” is not going to take playing time away from the starter or his backup; he steps in only if the other two are out of the game.

However, if a voter doesn’t want to do ranked-choice voting, she doesn’t have to. She can just vote for her top pick and be done with it. Or she can pick her first and second choices and leave the rest blank. Doing that just means the voter won’t have a voice in subsequent rounds, should they occur.

There are wrinkles to the system. Should there be seven or more candidates in a race, it is theoretically possible that some ballots would be exhausted, because their top-pick was eliminated, and their second, third, fourth and fifth choices were used in subsequent rounds. That outcome, however, is very unlikely.

No one knows for sure just how this system will affect the outcome of the 2021 races. One certainty is that, for voters to really make informed use of the system, they’re going to have to know more about the candidates—enough to know not just who their favorite is, but also whom they’d take in a pinch.

Because, really, does anyone want Cooney? I mean, look at the guy.

*Correction: The original version of this article misstated a key aspect of RCV. While a candidate only needs to clear 50 percent to win the race on the first round, once the ranking mechanism is triggered, the counting proceeds until there are only two candidates. In our example, even though Al-Hasan clears 50 percent in Round 4, there is still a Round 5. Thanks to commenter Evan Harper for pointing out the error.

10 thoughts on “How Will Ranked-Choice Voting Work in NYC? Let’s Pretend.”

Thank you for somewhat clearing this up. But why does it still smell like a scam to me? RCV will only take place in the party primaries, not in the general election??

It is a scam and many older voters will only vote for one person. I am afraid about their vote. What happens if I vote for the same person six times? Is there a way to stop me from doing that?

If you voted for the same person more than once it wouldn’t count. That’s because the system doesn’t take into account your 2nd and 3rd choices until your 1st choice has been eliminated. It that same eliminated person was in your 2 and 3 slot it would just be thrown away.

The mechanics of “Ranked Choicer” voting works similarly to “Proportional Representation”, which was used for years in NYC Council elections, and more recently in local School Board elections. In both cases the voter marks the candidates on their ballot choice #1, #2, #3, etc.

The difference was that all the City Council candidates in a boro ran against each other for the Boro’s share of the seats in the Council. The mechanics of counting the votes is the same: after each round of vote counting, the next choice on the loser’s ballots are distributed among the remaining candidates. The election ended when the number of candidates was finally reduced to the number of available seats.

“Ranked Choice” is different because all the candidates are competing for one seat. The winner is the one who finally gets a majority of the votes.

In both systems the ballots look the same, and the voters mark them the same way.

I don’t understand the primary. Is RCV going to be used in the primary? Let’s say for mayor – All the candidates are going t be in one pot no matter their party? So if one candidate ends up getting a majority of votes wins mayor and there will be no general election? It doesn’t make sense. If you do RCV per party at the primary that doesn’t make sense. Please explain the difference between the set up for the primary vs the set up for the general election. Thank you.

Ranked-choice voting won’t occur in the general election — it’s only for primaries and special elections.

The primaries are in June. If more than one mayoral candidate comes forward in any party, there will be a separate primary for that party, and if there are more than two candidates in a party, there will be ranked-choice voting in that party’s primary. (If there were only two candidates in a primary, you wouldn’t need ranked-choice voting because one candidate would have to win a majority on the first round, barring a tie.)

Right now, it is all but certain there will be a Democratic mayoral primary featuring ranked-choice voting. It is unclear whether the Republicans, Conservatives, Greens or others will hold a primary.

But there is a general election no matter what. It will feature the winner of the Democratic primary and the nominees of the other parties, whether they are named via primary or by default.

This is different from the two-round, nonpartisan election system used by some other states. That is where all the candidates are thrown into one pool and, unless someone clears 50 percent, the top two finishers move on to a decisive final round. NYC’s system will be different from that.

Ranked-choice voting has been employed on college campuses for years.

But the contests are never for positions which can affect one’s

finances and/or safety.

And explaining why the candidate with the most original votes did not win is like

explaining how the Electoral College works. I.E. if you have to explain it,

you realize that it’s less democratic and representational.

Wow so the days of a candidate squeaking out a primary victory with 30 – 40% of the vote (ex: de Blasio, 2013; Ferrer, 2005) are gone. Interesting, because those were usually the candidates supported by the Latino and Black communities (vs. Quinn and Weiner/Miller) those years, respectively.

This article is in error. As the ballot initiative said,

> A candidate who receives a majority of first-choice votes would win. If there is no majority winner, the last place candidate would be eliminated and any voter who had that candidate as their top choice would have their vote transferred to their next choice. This process would repeat until only two candidates remain, and the candidate with the most votes then would be the winner.

The process is not halted at 50 percent plus one. The elimination and reallocations continue until a final count is produced representing all those who expressed a preference between the two most popular candidates. So you can win by 60 or 70 percent even after many rounds of eliminations and runoffs.

I think that ranked choice voting will not achjeve the goal of many voters.