‘Without increased funding to make up for structural losses at schools, the institutionally racist chasm of inequity in education will continue to grow wider as students least served by city and state governments are left to suffer from resource deficits.’

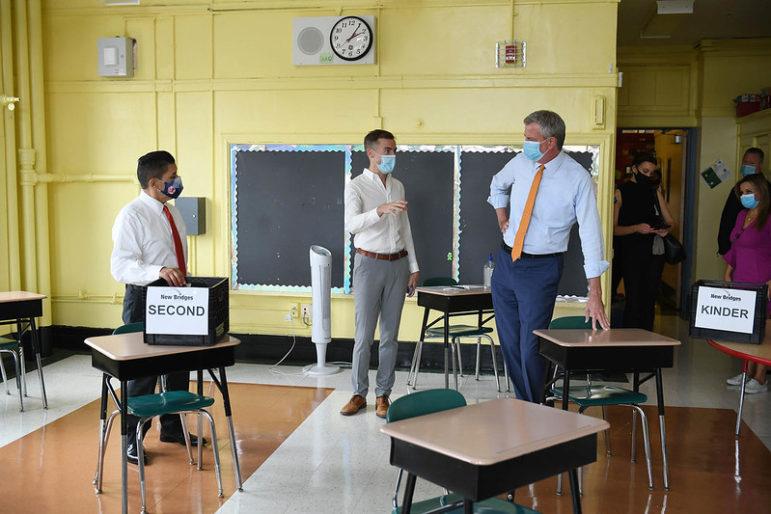

Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office

Mayor Bill de Blasio and Chancellor Carranza tour New Bridges Elementary to observe the school’s PPE delivery and reopening preparations. New Bridges Elementary, Brooklyn.The COVID-19 pandemic is devastating my school community. Haphazard and negligent responses from the city and state governments ensured that we did not have time to prepare. Schools were given less than a week to restructure lessons for a fully virtual space and to inventory and distribute building technology to families. At the end of that week, on March 19, 2020, New York City Department of Education (DOE) Chancellor Richard Carranza admitted, “We’re not going to have 300,000 devices by Monday. We never said we would.” He referred to the city’s estimate of the amount of technology still needed by families to continue their education remotely—technology that would come from whatever schools had to give to ensure continuity of education for their students without support from the DOE. In addition to the trauma of the human toll taken by COVID-19, the devastation caused by the pandemic took a significant toll on our school’s resources.

Our school was fortunate. Among our ranks at the Bronx Academy of Letters are professionals in navigating the structural inequity of the New York City public school system. Our school serves a low-income community in the poorest congressional district in the United States. We regularly strive to combat the effects of institutional racism on our school community. Before the pandemic, through hard-earned grants and donations, we were able to provide most of our students with a Chromebook to bring our classrooms into the 21st century. With our school’s technology being largely defunct and unreliable, these Chromebooks were tools of equity at my school.

Even so, in March 2020 we found ourselves stripping our school of whatever hardware we could sacrifice to give to students who needed devices to continue their education remotely. We handed out whatever school sets laptops and iPads we had, as well as personal class-sets of devices that were purchased through fundraising efforts by individual teachers.

In 2017, I fundraised over $4,000 from friends, family, and old colleagues to purchase a class set of Chromebooks to launch our school’s computer science program. All of those personally acquired devices were distributed to students at the beginning of remote learning to facilitate their continuation of education. Still, our school had to fundraise for even more technology to support students after we ran out of devices to give and for when those devices inevitably malfunctioned or broke.

When we go back to school, the years’ worth of collective effort by our staff to mitigate the inequity of funding to public schools will have been wiped out. The goodwill of repeat donations is unsustainable with the slowing of economies everywhere. More than ever, our school needs increased funding to recuperate from the devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the good fortune of hardworking teachers among us, we are entering the next school year (and years to come) without the resources we worked so hard to obtain.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

This reality is a problem that exists for all low-income serving schools in New York City. Without increased funding to make up for structural losses at schools, the institutionally racist chasm of inequity in education will continue to grow wider as students least served by city and state governments are left to suffer from resource deficits. All while they continue to be held to the same standards as students at better funded and better resourced schools.

Despite the traumatic effects of COVID-19 on school communities, in July 2020, Mayor Bill de Blasio attempted to pass a budget that would cut key services including the Single Shepherd program — an initiative that places 130 counselors and social workers at schools in historically under-served neighborhoods. Thanks to unyielding pressure put on the city by activists, educators, students, and parents, the mayor “found” the money to maintain some of these essential services.

Governor Andrew Cuomo will have you believe that there is no money left to give to schools as he reflexively deflects responsibility for funding deficits. He is attempting to redirect 20 percent of state aid from schools, which amounts to $5 billion. Cuomo’s argument is that the money is needed elsewhere to stimulate the economy, actively disregarding public schools’ role in stimulating the economy by providing quality equitable education to New York’s youth and future workforce. To quote a fierce champion of human rights and self-advocacy, Malcolm X, “Education is an important element in the struggle for human rights. It is the means to help our children and our people rediscover their identity and thereby increase their self-respect. Education is our passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs only to the people who prepare for it today.”

Government officials of all sorts talk about the importance of opening schools. They say that we’re a pillar of the economy. They talk about schools without including teachers’ voices. As pillars of the economy, we ask that no matter what decision is made regarding opening schools, invest in us. In normal years, we fight uphill battles for equity in funding, and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing inequities in school funding, we ask that you cease shortchanging a pillar of the economy and invest in public schools.

Mohammad J. Ahmad is a public high school teacher at the Urban Assembly Bronx Academy of Letters in the Mott Haven neighborhood of the south Bronx. Entering his 5th year in education as of the 2020-21 academic year, Mohammad has taught Algebra 2, Pre-Calculus, Psychology, Arabic, and Computer Science courses at the Bronx Academy of Letters. In 2020, Mohammad earned the Amazon Teacher of the Year award for the impact of his computer science classes on his students.

One thought on “Opinion: Open, Hybrid or Fully Remote, NYC Schools Need Aid, Not Austerity”

As a proud teacher to this young man, I say, thank you. Thank you for saying what needs to be heard. Thank you for making my work valuable in your hands. Thank you for continuing the vocation of education at its finest hour. When most in need, education is a creed.

Dr. Pugliese