United States National Guard

Hospital beds line the floor of the Los Angeles Convention Center as a part of the COVID-19 pandemic response.COVID-19 has killed people of color at a higher rate than Whites even when poverty is not part of the equation, a study release Tuesday found.

The report by scientists at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine looked at the rate of COVID-19 deaths through May 10 in 158 urban counties encompassing what is called the “combined statistical areas” of New York, Boston, New Orleans, Detroit, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Miami, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Seattle. They then assessed race and poverty statistics for each county, and divided the counties into four groups based on their racial breakdown and into high- and low-income categories based on their poverty rate.

Then they crunched the numbers and found that, even among high-income counties, the death rate in predominantly nonwhite counties was three times that for predominantly White counties.

However, poverty is clearly still a crucial factor in shaping death risk: In low-income counties, those with majority nonwhite populations posted a death rate nine times higher than low-income counties where Whites dominated.

“This divide or disparity is, of course, very high for nonwhite counties in high poverty areas—I guess as expected,” says Samrachana Adhikari, an assistant professor in the Department of Population Health at NYU’s Grossman School of Medicine and the lead author of the study. “But even in low-poverty counties we still see this disparities in deaths and cases.”

In other words, ascribing higher death rates to poverty and the health vulnerabilities that come with it fails to capture the full story. “Poverty does not explain all of the racial disparities,” Adhikari adds.

The research was published Tuesday in JAMA Network Open, a publication of the American Medical Association. The trends it reports are in line with the more granular data that New York City has provided. Death rates increase steadily with poverty, from 124 deaths per 100,000 in low-poverty areas to 267 per 100,000 in high poverty areas. And there is a clear racial skew: The death rates for Blacks (260 per 100,000) and Latinos (245 per 100,000) are starkly higher than for whites (123 deaths per 100,000) or Asians and Pacific Islanders (110/100,000).

The picture suggested by the city’s data grows slightly more complicated when looking at geography. The Bronx—the city’s poorest and least white borough—has endured the highest death rate. But Queens, which actually has the lowest poverty rate among boroughs but has the second-smallest share of whites, is second.

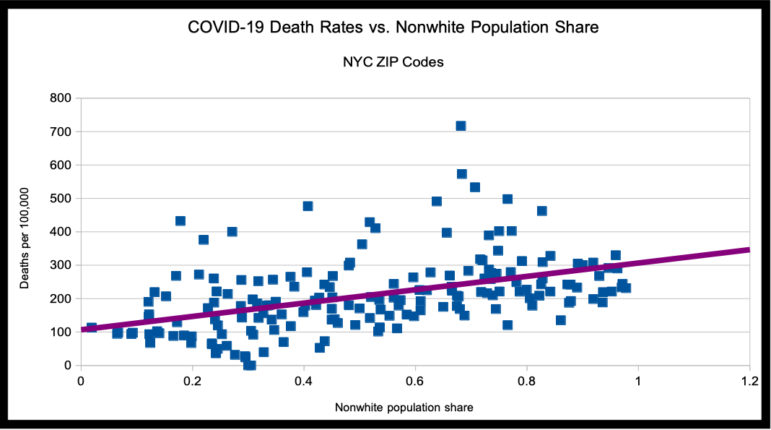

A crude look at death rates and racial composition across the city’s ZIP codes shows some relationship between higher nonwhite population and higher death rate, but there’s a lot of noise.

DOHMH data/City Limits analysis

Other factors are also at play. The death rate among men (282 per 100,000) is significantly higher than that for women (172 per 100,000). The oldest New Yorkers—those aged 75 or older—have had the highest death rate, at 1,689 per 100,000 people, versus 21 deaths per 100,000 for 18- to 44-year-olds.

Indeed, authors of the NYU study acknowledge that by looking only at the county level, the study misses the way race, poverty and death might interact within counties.

“We know in some of these counties there is more diversity and some variations” in COVID’s toll, Adhikari, says. “We also really haven’t accounted for other individual or community-level factors. Individual-level health factors are important in making someone more susceptible to COVID.”

Differences in death rates among counties could reflect where health facilities are located, varying degrees of household crowding, different dependencies on mass transit and other factors.

“For me it just opens several other questions that we should investigate,” Adhikari notes, particularly because, since May, the pandemic’s geographic focus has shifted from the West and East Coast to the South, and from cities to suburbs and beyond. “I think research like this should help policymakers or people who are responsible for improving health to make decisions for how to prioritize resources.”

One thought on “People of Color are Dying at Higher Rates from COVID-19, Despite Class”

This is just more noise.

Death rate, one each, hasn’t changed over time. Mortality count is more instructive. Too bad you don’t identify the ZIP’s. Then we might learn something. The infection rate early on in my ZIP, 11232-Bush Terminal, was a quarter that of the next ZIP east of us, 11219-Boro Park. I’ve never seen any numbers of deaths by ZIP yet. That would be dangerous information.

I’ll wait for more detailed, post-action, reporting. Just how does the Orthodox rate compare other-white rates?