Adi Talwar

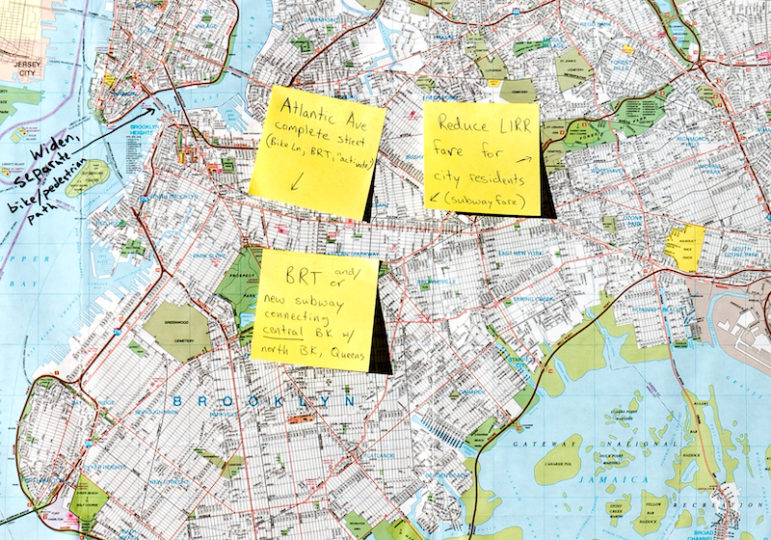

At a 2017 City Limits event, members of the public indicated how they would reshape the city’s transit system. The authors argue that the low ridership created by the pandemic—and the economic and social disparities laid bare by the disease—make it imperative that the system be redesigned now.As American cities gradually reopen for business, millions of New Yorkers have been asking themselves the same question: How will I get myself safely to work?

The recent recommendation from the CDC — drive yourself, alone if possible, and avoid public transportation — has done little to clarify the answer. On a typical weekday (before the coronavirus pandemic), the population of Manhattan would swell with 1.5 million commuters, most of them arriving via packed subways, trains, buses, and ferries. Only 27 percent of New Yorkers regularly drive to work, and fewer than half own a car.

Aside from well-founded concerns that increased car traffic will worsen gridlock and pollution, the recommendation brings an even more fundamental issue to light. Driving to work is a privilege that not all can afford; in fact, the idea goes against the spirit of a city built on robust public transit, the very infrastructure that has enabled its growth and prosperity over time. Access to transportation has always been a key to economic and social mobility in New York City, and this widespread access has provided opportunity for generations of its most underserved citizens.

The subway, for all the challenges that have rattled it in recent years, still embodies this egalitarian ideal. It runs on a flat fare, unlike the transit systems in many cities — there are no zones, no tiers. The subway is one of the greatest expressions of our democratic city — a place where people of every age, race, gender, nationality, and economic background come together, sharing the same crowded space on their individual journeys.

The coronavirus outbreak has changed that picture, bringing economic and social disparities into sharp relief. Subway ridership plummeted by more than 90 percent at the peak of the pandemic. While transit riders have begun to return in recent weeks as the city progressively reopens, fears of contagion and the need for social distancing continue to keep the majority of straphangers away. Millions of office employees continue to work from home, but for thousands of others, remote work is not an option. Many essential workers, and especially those from lower-income communities, have continued to rely on buses and trains each and every day.

Through it all, the trains have kept running—but now, the MTA faces the most significant fiscal crisis in its history. With a steep decline in revenue from fares and future funding uncertain, the agency now estimates a $10 billion deficit over the next two years. Capital projects, including desperately needed infrastructure upgrades, are now on hold.

As the city and its agencies adopt austerity budgets, ambitious new transit projects may be difficult to achieve for some time. Even still, we can’t afford to miss the opportunity to address an even larger challenge: to imagine what a more equitable city would look like. What solutions can we implement now to provide the reliable transit that New York City needs for its recovery—especially its most underserved communities?

The process starts with listening: city leaders, planners, and transportation agencies should open a broad dialogue with the communities who rely most on transit. It’s important to understand how to best serve transit riders’ needs in the long term, and significantly, what will help them feel safer right now.

Social distancing will remain an imperative until a vaccine is developed and made widely available. This means we need to fundamentally rethink the way our transportation systems serve those with the greatest need. For now, we must dramatically reduce demand for transit during peak hours. Employers should encourage all those who can to continue working from home, and also allow for staggered work hours to reduce rush-hour crowds.

At the same time, we must expand other transit options, providing as many as possible. Ferries, bikes, scooters, and other services can relieve pressure on subways and buses. The city should expand bus service and create more temporary protected bike lanes. A safe reopening requires not an “either/or”, but a “both/and” approach — we need to implement all of these ideas, and more.

By shaking us out of our routines, the pandemic has provided the occasion to imagine a different, better future. We should seize this moment to make long-term plans for a more equitable city, with a range of transit options that are convenient, reliable, accessible, and improve quality of life. The right solutions may be different from one neighborhood to the next, so it’s essential to work directly with each community to imagine this future together. Every project should also contribute to dramatically reducing carbon emissions, which will allow us to face the even greater environmental crisis on the horizon.

The temporary shutdown has given us a glimpse of some of the benefits that reducing vehicle traffic provides – reduced emissions, cleaner air, and fewer traffic fatalities. It’s time to make permanent changes for a city that is less car-centric, more walkable and bikeable, with a multitude of transit options and shorter commute times. Today, a vast proportion of our streetscape is given over to cars, including more than 3 million on-street parking spaces, which amount to a free or highly subsidized amenity for private vehicles. What if more of this space was used for express bus lanes that will help millions of New Yorkers get to their destinations faster? What if more of it was dedicated to pedestrians and cyclists, and made available for rain gardens and street trees? By rebalancing the priorities, we can create multiple benefits at once.

We should fill the gaps in the system, focusing first on serving the communities that lack access to reliable transit. We can expand bikeshare, ferry service, and even introduce new modes such as urban gondolas, which are relatively inexpensive and could turn the daily commute into an extraordinary experience. Urban mobility should be uplifting as well as effective, and these options should be affordable to all. Reduced fare programs for New York City transit and Citi Bike are a worthy initiative – the city should extend these benefits to any new transportation modes as well.

Of course, we need to renew our investment in the subway, which will remain our most vital and accessible transit system. This period of low ridership presents an unprecedented opportunity to get the work done to maintain and improve this aging infrastructure.

Transit agencies need to put greater emphasis on designing stations that are spacious and easy to navigate, filled with light and air. Stairwells and entryways must be enlarged to ease crowding. Elevators will need to be added, as fewer than one in five stations are currently accessible to people with disabilities. The MTA should consider continuing the overnight closure beyond the pandemic in order to fast-track these projects. But in this moment of opportunity, it is critical to provide for those in need and offer alternatives to commuters with few options. As the system is improved for all, let’s not impose an undue burden on those already shouldering more than their fair share.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

Another strategy is to reduce the great travel distances and long commute times that disproportionately affect low-income workers. We should promote the development of a city with multiple centers — beyond the Manhattan-centric model, and toward the continued growth of downtowns in many neighborhoods. With job centers distributed more broadly, more people would have the possibility to live within an easy walk or ride from their workplace. Other cities like Paris and London are setting ambitious examples to follow.

These changes may not happen easily, and many will come at a significant expense. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible to find solutions. Investments in transportation infrastructure are critical to the future of the city, to keeping New York a place of opportunity for all. The social and economic mobility delivered by inspired public works of transport should in fact be the cornerstone of our recovery plan, with the potential to create thousands of jobs. New York will eventually come booming back — and when it does, our transit systems must achieve their original ambitions and fulfill the bold promises they once held, as an engine of growth and prosperity for all citizens.

Keith O’Connor, AICP, LEED is a Director of Urban Design and Planning at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and Luke Bridle, AIA, LEED AP BD+C is an Associate Director at SOM.

One thought on “Opinion: COVID Gives NYC a Chance—and Urgent Reasons—to Redesign its Transit System”

Before “reinvesting” in the subways, let’s commit to keeping it free of the “homeless,” and give the MTA the duty and power to keep it so. Aside from the stench, and the sprawling across seats in crowded cars, the “homeless” bring a health risk ranging from parasites to worse. In any epidemic, they are an ideal disease vector waiting to happen. Until that is done every dollar spent is another dollar wasted on a system our leaders are unwilling to protect.