Pbroks13, Gordon Parks, Qwerthero

Accelerated by the pandemic, the future of the physical classroom is in question. Governor Andrew Cuomo suggests we “reimagine education,” and wondered at a recent news conference why, with the technology available to teachers and students, the “old model of everybody goes and sits in the classroom” persists? This perspective—that in-person education is somehow outmoded—has vehement supporters and critics. Such is the enduring and often contentious debate over remote learning.

The pandemic has forced faculty and students to rethink how we teach and learn and what might be the future of the university. The future of the university is a hot topic right now, with articles and blogposts rapidly circulating. Some pieces imagine a corporate/Facebook collaboration with elite campuses. In this future, technology drives instruction and removes much of what we currently view as intrinsic to the college experience.

Remote education involves physically separating teachers and students while supported by available technologies. Remote learning is not new. In the U.S. in the 1890s, William Rainey Harper, the first president of the University of Chicago, promoted correspondence courses conducted via mail. Remote learning was practiced across the 1920s and 1930s, when the majority of the US population still lived outside of cities and away from college campuses. The Open University founded in the U.K. in the 1960s offered remote learning and the popular model spread across Europe. Remote learning was lauded to me in the mid-1990s, not long after the internet changed our lives forever, by my dissertation chair, as the future of teaching and learning.

Because of the pandemic, millions of Americans are now engaged in some form of remote learning. Many are excited about this as they believe that now, finally technology will transform American education.

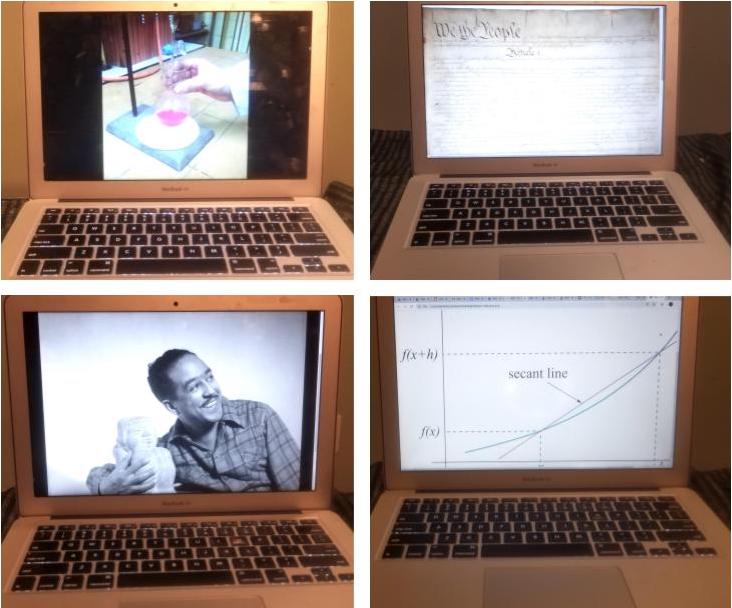

Of course, technology should and will shape how we teach and learn. This has been the case from Noah Webster’s Blue Back Speller to online resources, from the abacus to graphic calculators. I welcome how technology and online tools have enhanced my teaching and my students’ ability to learn. However, education’s response to the pandemic—which catapulted us fully online at breakneck speed—must be understood as an emergency measure, not an overall best approach, which it is not.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

As a college teacher I am interested in how the pandemic has altered how we currently teach and learn. Many of us had less than two weeks to rework in person courses. Many of us attended trainings and read articles that were quickly made available to help the transition to remote education. Remote teaching practices encouraged by most colleges and universities—video conferencing, pre-recorded lectures, supported by websites that allow students to post assignments and access resources—are considered “best practice” supports for remote education. But not everyone is effectively implementing them, and what is more, a large number of faculty members (many of whom are researchers first, teachers second) are not trained in pedagogy, whether in person or online.

Many argue that moving schools and colleges online due to the coronavirus has brought advantages and opportunities. Since mid-March, teaching and learning online allowed students to continue to receive instruction and complete courses. My graduating seniors will receive credit for this radically altered semester. Colleges will continue to receive tuition while moving summer classes online. Facebook is working on a competitor to Zoom, and other technology companies will develop and sell new products. Some students prefer online instruction, such as the 8th grader who wrote in The New York Times that she was relieved to be rid of disruptive classmates. Some college students are relieved not to have to commute an hour or more to campus.

But what is lost at Zoom U? My students unequivocally say they want to be back in the classroom. You might assume that the problem is me, that I am failing as a remote educator. But as I shelter in place with my 19-year-old college freshman son and 15-year-old tenth grade daughter, I get their feedback too on online learning. They wholeheartedly agree with my students. There is much lost, my students and children say. They describe online assignments resembling busywork, little to no online class discussion, less accountability for students and teachers, and hours spent staring at screens.

What else is lost at Zoom U? Remote teaching is teacher centered. When on Zoom, my students silence their mics so to minimize background noise. Otherwise, the sirens and squeaky dog toys or babies crying interrupt the session. Students contribute to discussions by typing comments in the thread at the right of our screens, or by typing “RH” for raised hand, if they want to speak after unmuting. I read students’ written comments out loud, in order to give their words a human voice. Generally, students who are not confident writers do not write comments in the thread. This includes my English Language Learners. Students who do not want a close up of their face (or profile picture) at the center of the screen do not request to speak. Students who are ashamed of their homes or are hiding in a closet so to have quiet in a crowded, small apartment—do not participate either. So many of my students are silent, while the confident and vocal and literate students use Zoom to their advantage.

Remote learning removes the interpersonal aspect of the classroom setting which helps many students maintain the focus and motivation required for academic success. Every semester I have students who engage with my course more seriously after we have one on one conversations after class or during office hours. Since remotely teaching my classes, two of my students have completely fallen off the radar.

Teaching in any setting is a two-way street. Most teachers know this and can share stories of how they learn from their students. The Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire wrote about the possibilities for teachers and students to view one another as both students and teachers. This scenario invites students to pose their own questions, and ultimately to engage with their world critically, proactively and meaningfully in school and in life. Teachers in this context recognize that the classroom supports academic as well as social growth in students. The latter involves relationships—student to student, and teacher to student—because the act of applying content learned to real life examples and scenarios is enhanced by exploring ideas in groups, and I argue, in person.

Those who imagine the future of the university as a catalogue of online classes might ask college students and teachers how things went these past two months? Were teachers and students inspired by remote learning? Were college teachers able to convey the depth and complexity of their fields and research to students while teaching online? Will they be able to write letters of recommendation for students they hardly got to hear from this semester? Did students connect with one another intellectually and socially while learning remotely?

What is lost after leaving classrooms where students and teachers once gathered? What practices are helpful now and should be continued? We must seriously consider these questions, and especially when we are able to resume daily activities—such as gathering in groups. I look forward to seeing my students in person as they strive to develop as scholars and human beings in ways that only in-person college experiences can foster. And my students are eager to return to our campus classrooms as soon as they can.

Sonia E. Murrow is an associate professor of education at Brooklyn College.