Jarrett Murphy

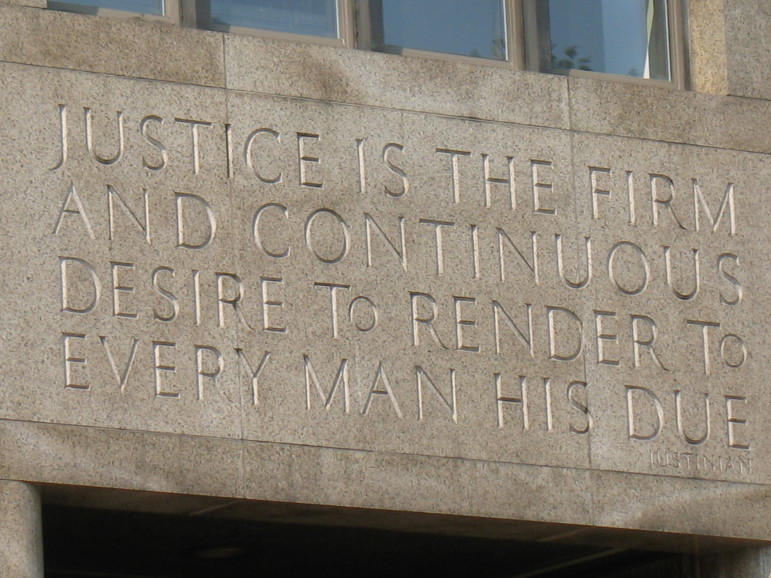

The facade of the criminal court building in Manhattan.Since the pandemic began, my role as a public defender has completely shifted. My new client base is anyone and everyone in custody.

After giving my cell phone number to three of my clients in custody, I have gotten more than 20 calls from people in more dire situations in Rikers. All these men are afraid for their lives and looking for anyone to help. My ethical obligations are to my clients, of course, but the human in me takes every call.

These men have no idea what is going on outside the jail. They do not have the luxury of watching Gov. Cuomo every day on the news networks. They only know how terrifying COVID is from what they see right in front of them.

One of my clients diagnosed with COVID was found breathless on the floor of a hallway. No one would touch him. He continued to lay there for 25 minutes before a squad of armored corrections officers literally dragged him to a bus and took him to the medical facility. A few weeks earlier, this client had been showing symptoms that were moved to the medical facility. After a week, the medical staff sent him back to his housing area. He collapsed while trying to drag his 50-pound bag of possessions back to his dorm.

My role as an attorney has shifted to include dispatcher, secretary, and researcher. Men take the jail phone one by one to ask me questions. They beg me to contact their families so I can tell their families that they love them in case they die. My heart breaks during those calls. All I want to do is reassure them that they will be okay but the reality is that I cannot assure them of that. No one is safe in Rikers.

Between screening calls, I use every route possible to get my clients out of custody. For one client with underlying health issues who is over 50, the journey to try to get him out of custody began the first week of April.

I spent two weeks attempting to get him in front of a judge just to take a plea. The court requirements change almost daily making it impossible to coordinate with someone in custody. For example, the court requires a signed and notarized affidavit. That seems simple enough to us on the outside but the logistical problems are endless when someone is in custody. Something so simple as emailing a document and printing it out is normally an enormous challenge for someone in custody, and next to impossible with a lack of staff during a pandemic.

We finally got a court date but my client still had a parole hold. For another two weeks, I gathered and filled out the six documents required to request removal of the hold. I worked nonstop to get in touch with his parole attorney, update the writ, and obtain medical documents. To get medical documents you need to read a two- page affidavit to the client. That’s 10 minutes’ worth of phone time, but clients only get 14 minutes every two hours.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

Finally, after more than 100 hours of work on this case, the writ date was set. I sat in my living room with my sweatpants, dress blouse and suit jacket on and argued the case. It was denied. My heart sank.

I immediately thought about how my client was going to react when he heard the news. I knew he would call at 5 p.m.; from the time the writ ended until 5 p.m. seemed to be the longest hours of my life. When he finally called his reaction was just as upsetting as I had imagined. He was silent for 30 seconds. I began to explain how the judge had decided before I even started, how it was unfair, how sorry I was. It finally hit me that he does not care about any of that. I stopped in the middle of my rant and told him I’m sorry, I’m just so sorry. I know none of that matters. He told me he’s going to need a little time and hung up.

This is only the story of one client. These emotional rollercoasters are never-ending. Meanwhile, arraignment shifts go until 2:15 a.m. each night. Those clients are filled with anxiety that of bail they cannot pay might be set. Orders of protection can leave clients out in the streets for months between adjournment periods.

As a public defender, my job is to protect my clients’ liberty. That stress of that challenge comes with the job, but it’s magnified in times like these. Yet I find myself more in love with my job than ever.

Samantha Tucker is an attorney at Queens Defenders.

One thought on “Opinion: The Life of a Public Defender When COVID is on Offense”

I wish the public defender my son had felt like you. He violated his rights, DID NOT admit his mistake that caused my sit to sit in jail 8 months cause he lied to us and the judge. Instead of helping my son he helped the DA. Told my son his only choice was to take a plea and said the DA said he had to go to prison. This is my son first felony first time in prison. Others that where involved in the crime with my son two who already had felonies got NO TIME. My son was sent to the worst prisons in Mississippi he has been beat by other inmate alway 3 or more at time some days wasn’t allowed to eat some days only 1tray when he could eat sleep shower or make a call this is by the gangs not guards but they are no better. Been living in inhuman conditions having to fight for his life every day. I have prayed someone anyone would help but if you don’t have money you don’t matter. My son has a 8 year old son that misses his daddy bad and a 5 year old daughter that has the Rare form of Polymicrogyria she can’t walk, talk, sit up, or hold her head up has a feeding speck in her belly breathing problems and is in and out of LeBonheur Children’s Hospital and has many Seizures daily and by many doctors that she will be lucky to make it to age 10. I have had to pay anywhere up to $700 a month so my son want be killed even have a proof of life video. I’m starting to think here in Tupelo Ms not one person in the whole justice system has a heart. Well thank you for letting me post. My name is Sandi I’m for Tupelo, Ms