Adi Talwar

View of the Northern shoreline of Edgewater Park in the Bronx. The neighborhood poses special challenges for resiliency measures, and few homeowners have taken steps to adopt them.

On the outskirts of the Bronx, alongside the Throgs Neck Expressway, there’s a private cooperative community. It’s governed through bylaws enforced by an active board. Getting to the coastal community of Edgewater Park requires time and patience. There are only two buses that’ll take you here, the Bx8 and BxM9. Upon arriving, you’ll notice American flags hanging high outside the single-family bungalow homes. They have their own fire company, the Edgewater Volunteer Fire Department. They have one deli by the name of Ruanes Deli of Edgewater. Edgewater Park gives a sense of being away from the city while still being in the city.

Along Emmons Avenue, the coastal community of Sheepshead Bay has retail stores, seaside restaurants, some senior homes and 10 piers with small ships. The ships provide tours or fishing trips. Located in the southern part of the borough, the neighborhood consists of small, single-family bungalows and multi-family apartments. If it weren’t for the MTA buses passing through Emmons, it’d be easy to forget that Sheepshead is part of New York City.

Northeast of Sheepshead Bay is the neighborhood of Canarsie. Next to the Canarsie Pier is Canarsie Park and the Fresh Creek National Preserve. During the warmer months, people come here to fish. This area faces Jamaica Bay. Entering the neighborhood from the Shore Parkway, the first set of homes one passes is the New York City Housing Authority Bay View complex. The Ocean Rock Condominium are just across the street.

On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy hit New York City, destroyed around 300 homes and damaged 69,000 residential units. Thousands were displaced. Forty-four residents died and the cost of damage and lost economic activity was estimated at $19 billion.

Edgewater Park, Sheepshead Bay and Canarsie were each impacted by Sandy, to varying degrees. They were selected to be part of a city planning study called Resilient Neighborhoods, which focused on communities facing unique risks for coastal flooding that gave recommendations to harden them against those dangers. The initiative produced plans in the spring of 2017.

Two years later, and seven years after the superstorm, there has been some progress toward making New York City as a whole—and the Resilient Neighborhoods in particular—safer. But much remains undone, thanks to the challenges facing individual property owners and the complexity of plans for regional coastal defense.

And now, hurricane season is here again. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center is predicting that between June 1 and November 30, nine to 15 named storms with winds of 39 mph or more. Out of those storms, four to eight will become hurricanes with winds topping 74 mph or more, and two to four storms will become category 3, 4, or 5 hurricanes with winds of 111 mph or more. NOAA provides this data with a confidence of 70 percent.

A plethora of plans

The Resilient Neighborhoods Initiative is one of many resiliency projects underway in the city and the region.

On March 14, Mayor de Blasio presented a plan to extend Lower Manhattan by two city blocks. The Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency plan would focus on the Lower East Side, South Street Seaport, the Financial District and Battery Park. Financing the $500 million plan is in its early stages. The money would likely come from state and federal funds. If the government does not provide funds, the city will look to the private sector.

The East Side Coastal Resiliency Plan (ESCR) was proposed on January 2015. It would rebuild the 2.4-mile stretch alongside the East Side, from Montgomery Street to East 25th Street. ESCR’s design would raise the sea wall by eight feet and protect the infrastructure around the East River Park for a 100-year flood. In 2014, the city was awarded $350 million for this work by the federal government. The city invested money into the project for a total of $700 million. The plan, which has stirred some controversy because of its impact on the park and its users, is moving through the city’s land-use review process.

NYC DCP

One of the tidal barriers being considered by the Army Corps.

Back in February, the US Army Corps of Engineers released an interim report on its move toward a long-term plan for coastal storm risk management in the New York area. Some approaches the Corps said they were considering included a harbor-wide storm surge barrier, a network of smaller surge gates or a system of flood walls and berms around the waterways. A final report for is set for 2021, followed by a recommendation to Congress. If approved by Congress, the plan could take decades to be completed.

The Corps has already made one decision that will impact New York’s coastline. In February, city and federal officials announced that Washington had agreed to fund the Staten Island Levee project—a 5.3-mile seawall to be constructed from Fort Wadsworth, around the foot of the Verrazzano Bridge, down to Oakwood Beach. The construction of this project will begin next year with a completion date of 2024 and a cost of $500 million. The project was approved and funded largely because the island has had studies since the 1950’s about the need for protective measures. When Sandy occurred, Staten Island officials wisely drew attention to that earlier research and were able to convince the feds to open their wallet.

Staten Island pols weren’t the only ones who saw a need to draw attention to resiliency needs. Two years after Hurricane Sandy, the City Council of New York formed the Committee on Recovery and Resiliency. It was chaired by Mark Treyger, the Councilmember for Brooklyn’s district 47, which is comprised of Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Gravesend and Sea Gate.

The resiliency committee was phased out at the end of the 2014-2017 term, but Treyger (who now chairs the Committee on Education) says he still keeps track of the city’s resiliency efforts. “I have sat through a number of PowerPoint presentations, a number of hearings with an array of government officials about resilience studies, ideas, plans, initiatives,” he says. “But we don’t have the resources to actualize these items then these are just ideas, and time is of the essence.”

Treyger believes vulnerable neighborhoods in the outer boroughs have not received as much attention as they should. “The city has invested more of its own resources in Manhattan than it has in other parts of the city,” he said. “The city of New York is investing hundreds of millions of dollars of its capital budget for Manhattan,” he says. “In Southern Brooklyn, they are giving us some resources but nothing on the grand scale of comprehensive approaches that you’ve seen in other parts of the city.”

He says that even the Corps is aware of the boroughs that are most vulnerable. “Even in their analysis, Brooklyn and Queens are the most vulnerable coastal areas in the city of New York to the rising threat of climate change and to the frequency of storms,” says Treyger. “There is no funded plan in place to better protect the most vulnerable parts of New York City and that to me is a very serious issue.”

A set of vulnerable communities

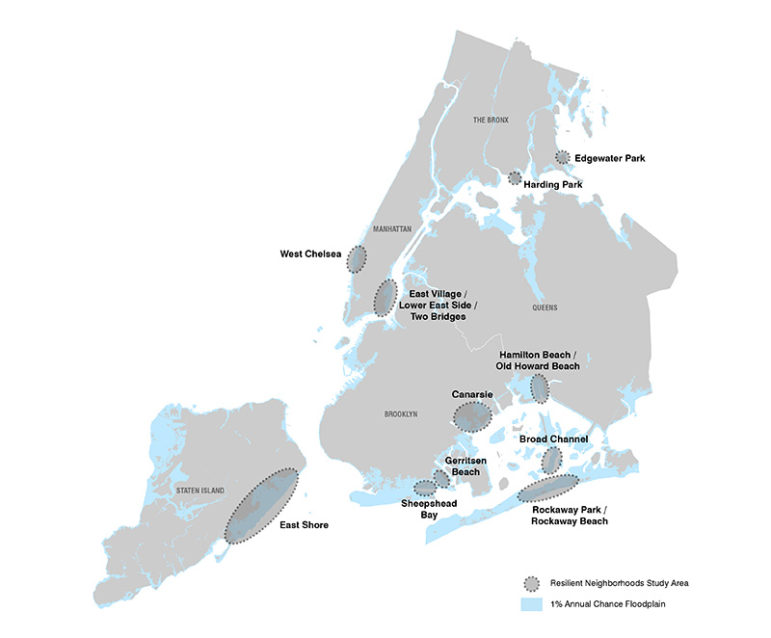

NYC DCP

The Resilient Neighborhoods communities.

The city’s online map of resiliency projects shows dozens of efforts all over the five boroughs. None of the planned infrastucture projects in the outer boroughs, however, rival the East Side and Lower Manhattan projects in terms of scale or cost. That could simply reflect the fact that while all of the city’s coastline is at increased risk, the nature of the threat varies from one neighborhood to another.

That’s a reason why New York City’s Department of City Planning (DCP) launched the Resilient Neighborhoods Initiative in 2013. Over the next three to four years, DCP worked alongside stakeholders of those communities to further examine land use and zoning and understand flood risks. The initiative was funded by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s Community Development Block Grant for Disaster Recovery, and it relied on public input gathered by the New York State Community Reconstruction Program and HUD’s 2014 Rebuild by Design effort.

The study looked at the East Shore in Staten Island; Canarsie, Gerritsen Beach and Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn; Hamilton Beach/Old Howard Beach, Broad Channel and Rockaway Park/Rockaway Beach in Queens; West Chelsea and the East Village/Lower East Side/Two Bridges in Manhattan; and Harding Park and Edgewater Park in the Bronx.

Those areas were selected based on damage caused by Hurricane Sandy or potential for damage from future storms—and because they each presented issues involving land use, zoning and resiliency that could not be fixed with citywide zoning changes. “Some communities suffered extensive damage, and numerous home and business owners continue to struggle to rebuild and recover. Others were largely unaffected by flooding in this storm, but remain at risk from future storms,” the initiative’s literature said.

The city says outreach was a major focus. There were 14 meetings held at Edgewater Park, 12 in Canarsie and 10 in Sheepshead Bay. In total, DCP has done 250 meetings with over 4,000 stakeholders across the city on resiliency work since Sandy.

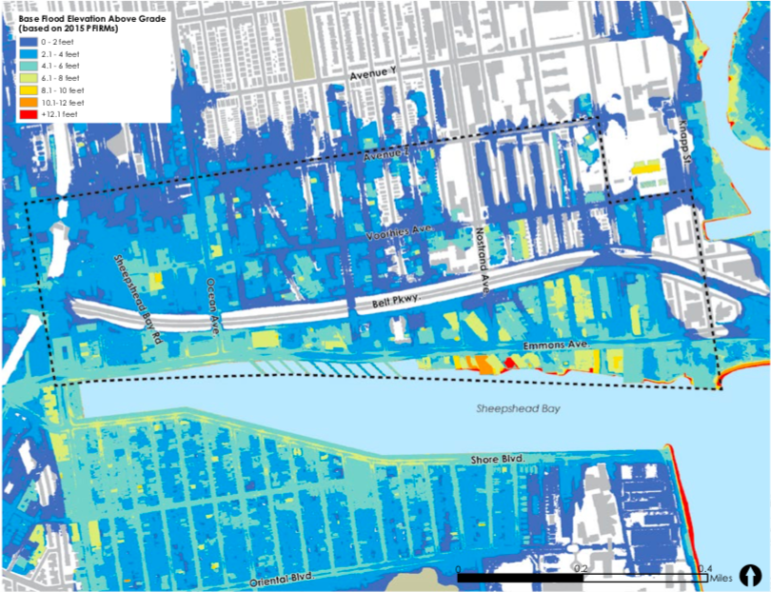

On the Bay, a concern for stores

Sheepshead Bay was selected by DCP not only because of the damage Sandy did but for its high chances of flooding from future storms. The neighborhood falls in the 1 percent annual flood plain , with waves up to 3 feet causing problems in some areas. In 2015, updated Preliminary Flood Insurance Rate Maps (PFIRMs) added 4,000 residential units and 1,500 new buildings in the neighborhood into the floodplain.

The Department of City Planning found there are specific sections of Sheepshead where flooding is worse, for example, its unique bungalow courts are subject to floods because of their low-lying typology.

But the focus was not just on residences. When Hurricane Sandy hit, it was a clear reminder of how a commercial corridor can be affected by a flood, and in turn affect the community that uses it. It was hard for a business to immediately reopen after the storm. According to the DCP report, some businesses never did.

NYC DCP

Flood risks around Sheepshead Bay.

The report found the retail area has to be retrofitted to bring attached buildings into compliance with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) but that could mean replacing cellar space, which is a challenge for business owners. It can be very expensive.

That’s why, when DCP mapped out several approaches to improve resiliency in the area, it included changes to the regulations governing the Sheepshead Bay special district that runs along the Emmons Avenue corridor. The changes would make it easier for commercial properties to comply with the new resiliency rules—for instance, they’d permit a slight increase in building height to create storage lofts to make up for basement space that was no longer feasible.

Theresa Scavo, chairperson for Brooklyn Community Board 15, tells City Limits there has not been any changes to the rules for the Sheepshead Bay special district so far.

Public plazas in the special district are an important part of the neighborhood but aren’t in step with best practices for resiliency. The new provisions would require steps to make plazas more resilient, as well as more attractive to the public.

Scavo says there has been progress on this front. “Any developer using the public plaza must maintain the plaza and leave it for public use,” she said. “The corner of Emmons Avenue and Sheepshead Bay Road is a prime example. They have provided seating for the public all around the plaza.”

A key concern now is about the elevation of homes. Homeowners are not required to retrofit their homes, but they face huge flood insurance premiums (not to mention flooding risks) if they don’t. “If you renovate an existing house and make it resilient, you would have to elevate the house or move all utilities above the first floor,” said Scavo in an email. “This would be extremely expensive.”

Coordination issues in Canarsie

Canarsie was selected because federal flood-map coverage there has expanded. Prior to the release of the PFIRMs from 2013, only a small amount of Canarsie was located within the federal flood zone and now two-thirds of the neighborhood is included. During Hurricane Sandy, Canarsie experienced waves topping seven feet.

DCP found a different web of challenges in Canarsie. There’s economic hardship: The neighborhood was hit hard by the subprime mortgage crisis. The rising cost of insurance premiums and the updated FEMA flood maps will be tough on homeowners. The good news is, if a home is compliant with NYC building code and FEMA standard regulations, it can lower premiums. Unfortunately, attached and semi-detached homes are hard to retrofit and it’s an expensive investment.

The resiliency framework for Canarsie was extensive. The focus was on zoning strategies for attached, semi-detached housing and detached housing and the revitalization of retail corridors and coastal protection.

DCP NYC

A City Planning engagement event during the Resilient Neighborhoods planning process in Canarsie.

Some of those needs were addressed by citywide policy changes after Sandy. The City Council adopted the Citywide Flood Resilience Zoning Text on October 9, 2013. Developed by DCP, which modified zoning regulations for retrofitting and rebuilding in compliance with FEMA and NYC building code standards. In the summer of 2015, the Council adopted an amendment by the name of the Special Regulations for Neighborhood Recovery that simplified the process for getting permits to rebuild homes built before—and therefore out of step with—current zoning in their neighborhoods. (City Planning is now gathering public feedback on another set of zoning changes, Zoning for Coastal Flood Resiliency, that would expand and make permanent some of the tweaks done after Sandy.)

One person who was involved in the study of Canarsie was Elizabeth Malone, the program manager of Resiliency and Insurance for Neighborhood Housing Services of Brooklyn. She says people in the community were impressed and welcomed the ideas put forward by DCP.

However, according to Malone, the amendments so far helped but didn’t solve the problem. “They helped a bit in determining what can be done and how to do it,” she says. “But the daunting challenges they do not address are financial: costs of retro-fitting, and the loss of income from basement rentals, legal or not, that are needed to pay the mortgage.”

Those financial challenges multiply when homes fall in the annual 1 percent floodplain, and require flood insurance. “The issue for the people in this neighborhood about the resiliency rezoning is that their next question is ‘Ok, we see what you can do. But who’s going to fund this?'” she said. “There is not going to be a one size fits all, simple solution.”

Nor will it be one that can be achieved one house at at time. “You have to be very conscious of what kind of hydro-static forces you’re going to be having along the entire street, not just the house you want to make resilient,” Malone says. All neighbors have to agree to raise the elevation of houses, she says, because otherwise making one house higher (and safer) can actually increase risks to adjacent homes. “Without neighbors deciding they’re both going to do this, it’s not actually doable.”

Unique charms and challenges in Edgewater Park

Edgewater Park occupies a shoulder of the Bronx coastline just north of the Throggs Neck Bridge. Making that community of 675 homes, 278 of which sit in a flood zone, has posed unique challenges. Since it is a private co-op, some of its bylaws create operational and regulatory challenges for a more resilient neighborhood. Although the community was not directly hit during Sandy (there was some moderate damage to structures but nothing like what was seen in Canarsie of Sheepshead), there is a high risk of future storms. DCP selected the neighborhood because of its unique flood risk challenges, its typography and the existing housing stock.

DCP found Edgewater Park is exposed to coastal storm surge elevations and a lot of wave action because elevating homes and investing in them is both financially and physically difficult. It is physically difficult to perform work on homes as they’re tightly packed next to each other and the narrowness of the roads does not help. The homes were built before floodplain management regulations. The only thing separating many of them from the ocean is a concrete pavement and a barrier made of wood and rope. Around 40 percent of the community is mandated to purchase flood insurance.

The first step in helping Edgewater Park was for the board to amend its bylaws to change the rules on the height of homes. This allowed the elevation of homes.

Next, after another round of meetings with the Edgewater board, coop leadership removed stipulations from their bylaws that didn’t allow for covered porches, planting, and stair turns. This change allowed for the design changes that needed to accompany elevations.

DCP NYC

Vulnerable homes and close quarters in Edgewater Park.

DCP’s report presented case studies, using homes in the community as models. The homes used in the studies presented challenges to retrofitting, including the difficult task of elevating a whole first floor, parking issues, obstacles to maintaining healthy and vibrant streetscapes, figuring out how to effect resident access to changed structures and relocating key parts of a home’s infrastructure.

Despite the changes to coop bylaws and citywide zoning rules, few Edgewater Park residents have actually taken on the challenge of elevating their structure. According to the Department of Buildings, since Superstorm Sandy, just one property in Edgewater Park “has obtained permits for the elevation of the existing building.” Four other properties ” have obtained renovation permits which indicated a “substantial improvement” of the property, requiring the project to comply with flood-resistant construction standards outlined in the NYC Building Code.”

What’s next?

The problem, according to Council Member Treyger, is that while changes to zoning laws and other regulations can can make retrofitting technically feasible, they don’t significantly improve the math facing homeowners. This is a barrier City Planning recognized. “Even if you change zoning laws there’s still an equity issue because working-class people cannot afford to make their homes resilient and rich families can,” he says. “That’s where things have kind of left off and they were mindful of that.”

Community Board 18 (Canarsie) of Brooklyn planned to have representatives from DCP address the board at the end of June about the citywide zoning text amendments, according to Dorothy Turano, the district manager of the board.

Malone continues to work with DCP because she wants something to be accomplished but to her it is an initiative that cannot be done until there is some sort of funding. “They’ve made an effort to come out to the community to showcase what’s going on, that is still continuing,” she says. “People are very practical,” she adds. “They say, ‘I see what I can do. I’m looking at $250,000 that I don’t have in my pocket.”

NYC Council

Mark Treyger, Brooklyn Councilmember

In Sheepshead Bay the Department of City Planning is meeting with community members to discuss an update of the special district rules.

And the Zoning for Coastal Flood Resiliency policy now under consideration will incorporate recommendations from the Resilient Neighborhood reports. These are new zoning measure would turn structures more flood resilient and would let homeowners and businesses recover quickly after storms in the city’s most exposed areas. “Zoning for Coastal Flood Resiliency would expand the area where flood resilient zoning provisions apply, more than doubling the number of buildings that could utilize these provisions,” according to DCP. “It would accomplish this by allowing buildings in both the city’s 1 percent annual chance floodplain and 0.2 percent annual chance floodplain to fully meet or exceed flood-resistant construction standards, even when these standards are not required by FEMA and NYC’s Building Code.”

The department will once again do outreach with the coastal communities as the proposal moves forward. The environmental and public review are set the begin at the end of the 2019.

Nature doesn’t follow the ULURP clock. The question remains whether New York City is ready for another Sandy-like storm. Treyger does not believe so. “I think we’re more aware of our weaknesses but to be frank, I don’t think it’s accurate to say we’re fully prepared,” he says. “I know there are still vulnerabilities that exist in many of our communities.”

3 thoughts on “Seven Years After Sandy, Slow Moves Toward Resiliency in High-Risk Nabes”

Pingback: Protecting Edgewater Properties from Violent Storms - This Is The Bronx

Pingback: Is New York Ready for the Next Superstorm?

Pingback: Nova York está pronta para a próxima super tempestade? | Blog Ambiental