J. Friedman

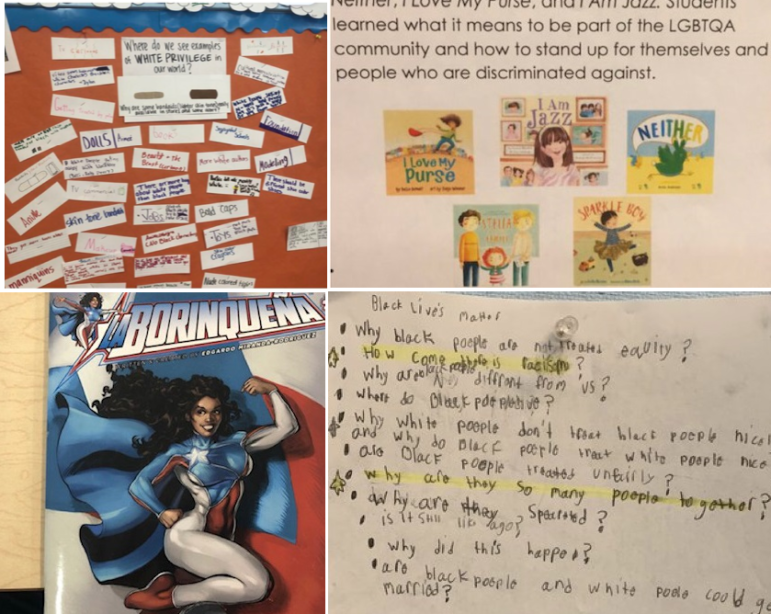

Scenes from a curriculum that sees color (and other human differences), and talks about it.

I am a White Assistant Principal of a New York City elementary school. My journey to being able to talk about race and how it impacts our students and schools has made a tremendous difference for me, my practice, and the young people I serve.

I grew up outside of New Orleans and had the opportunity to go to a public school that prepared me to go to and complete college. I noticed that some students in my school and other schools in my city had a very different experience. Reflecting back, I realize that these different experiences and outcomes had a lot to do with the privileges I carried as a White child from an affluent background. I went to college on the West Coast as a student of education and journalism. After college, I joined Teach for America and was placed at a New York City school on the Lower East Side.

From 14 years of experience as a teacher and now an assistant principal at the same school, I can tell you that developing an environment that creates equitable outcomes for all children is impossible without talking about race. I know because I tried. I became aware of White privilege after college and had informal conversations with my principal about the impact of race in our school, but it took 10 years before we were brave enough to address race directly with staff.

For 10 years, we worked to create equitable outcomes for our Black and Brown students by focusing on reading, writing, and math. While this helped lower the number of students performing at a Level 1, we still had a disproportionate amount of Black boys receiving suspensions and performing lower than other students. With the best of intentions, we were still perpetuating the same outcomes we were passionately working against.

I thought I was “progressive.” I was taught to say “I don’t see color” and to love everyone and treat them how you want to be treated. When I first engaged in conversations around racism, I remember my White fragility coming out through tears and comments like “I am not racist, I’m Jewish and we know what it’s like to be oppressed. My family was the only Jewish family in my entire high school!” Or “I have Black friends.” I am appreciative of my learning experiences both formal and informal that led me to understand that by not acknowledging someone’s identity, I am not acknowledging who they are—their experiences, the challenges that are unique to them, and that in our country people have different experiences based specifically on their race.

It was not until a few teachers gave us the nudge to talk about the White elephant in the room… specifically, the predominantly White teaching staff serving a community of color. We started by coming together as a school staff and self-assessing using the Continuum on Becoming An Anti-Racist Multicultural Organization. We were shocked to discover we were in the passive stage towards becoming an anti-racist multicultural school. We immediately formed an equity team to guide the work we knew we needed to engage in with ourselves and our staff. We began to talk about Whiteness and the three I’s of racism (institutional, interpersonal, and internalized). It was hard, and there was discomfort, there were tears, there was pushback. These difficult conversations were healthy and necessary—the work brought progress, awareness, accountability, reflection, and action.

Talking about race can feel so personal and White folks compare this to feeling attacked. But it’s not an attack, its discomfort and through it, we grew. A huge ah-ha moment for me was that confronting racism in my school is not about just me as an individual, it is about me and the systems and culture in which I am automatically a part of. We have to be willing to push through the discomfort for the sake of our students. Discomfort is such a tiny ask for the sake of changing systems and practices that are negatively impacting our students.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

Our school became a part of the CREATES (Culturally Responsive Environments Attaining Transformative Equitable Solutions) cohort, where we meet monthly with other schools to examine our practices, unpack the institutional racism embedded in our school system, and reimagine what schooling can look like. Last year, I participated in a mandated two-day training for school leaders called Courageous Conversation About Race, which helps educators to address persistent racial disparities intentionally, explicitly and comprehensively. I am blessed to be in my second year of the Critically Conscious Educator Rising Series provided by the DOE and NYU—one of the many equity-focused trainings being used throughout our school system.

As White folks, it takes practice talking about race, many of us were taught that “White” or “Black” are bad words. Through our equity work, our staff and I have grown together to understand that by seeing one’s identity, one can acknowledge the person as a whole—who they are and how that has shaped their experiences. These professional development opportunities have gone far beyond the traditional one-day workshops that schools are normally offered, they impacted our practice and sparked on-going conversations that have helped us grow both personally and professionally.

Previously, we did not talk about race. We talked about closing the “achievement gap” through strong instruction and differentiation based on standards-aligned units of study. Now we’ve shifted our language to naming the disproportionality that exists as an “opportunity gap” because the deficit is not in the children, it’s in the schools.

We now directly look for where disproportionality exists in our data and what shifts we need to make to address it. This has led to our school to design more intentional school-level reading and math intervention programs and redesign our data cycles to better monitor student progress. Now, we analyze our social studies standards to see whose history is not being told, whose history is being told inaccurately, and create our own units to include a holistic and accurate history. We try to ensure that our units of study question injustices and teach students about a variety of perspectives, develop empathy and design social action projects. For example, our kindergarten students wrote to publishers to demand representation of more and varied family structures in books. Our 4th grade students studied indigenous people and the impact of colonization. Our 1st graders read “The Colors of Us” and developed a love for their unique skin color by naming it something beautiful—like mocha chocolate chip. As a result, student engagement has increased substantially and so has student academic performance.

Before talking about race, we were unsure of why on our Learning Environment Survey, we received lower ratings from parents in areas such as “I feel welcome in my child’s school” or “I feel like the school partners with me for my child’s success.” Now, we reflect on our identities and the impact of how we are perceived. As a result, we have shifted our interactions with parents from teachers as experts to families as experts. For example, instead of launching the year with a curriculum night where teachers present to families, we have listening conferences where families lead by sharing with us about their child. Parents are now invited into their classroom for Star Reading and Math mornings, for publication celebrations, and to share about their family. Our survey results have improved dramatically.

Pursuing racial justice is not about having all the answers, it’s about taking the time to slow down and know that there is no right answer, that there will often be no closure and that the work is messy and will never be done. Throughout my personal journey of understanding my racial identity, I have gone through all the stages—denial, fragility, debilitating guilt, the savior complex, otherness, and I still visit those stages as my consciousness changes. New questions constantly surface. I have learned with and from folks who were patient with me even though they didn’t have to be and brave enough to bring my attention to harm that I may have caused. I roll my eyes at my earlier self who didn’t acknowledge color. This reminds me that this work is a true journey and that I must have a sense of urgency but be patient with myself. If I can shift my consciousness so can others.

I continue to take time to learn on my own. I read a lot, tweet a lot and follow amazing people on social media who I learn from daily. My journey is complex, but as a White school leader serving Black and Brown children, I have a responsibility to unlearn, relearn, and challenge my own complicity. I support the NYC DoE in investing funds into training all staff on implicit bias, developing equity teams, and other racial equity initiatives such as CREATES and CCER. Our school systems are creating one set of outcomes for White children, and another set of outcomes for Black and Brown children. It’s common sense: we cannot address the causes of these outcomes if we do not directly talk about race. I can’t think of a better investment that would impact our students.

Jodi Friedman is an assistant principal.

13 thoughts on “Opinion: What Happened When One NYC School Decided to Really Talk About Race”

This article gives me hope in many ways. Keep up the good work.

The elephant in the room is Asian students.. They do not seem to require anything except hitting the books, studying hard, and getting the results. They are not asking to ‘pursue racial justice’ except when the do-gooders take illogical steps to put them at disadvantage, despite the Civil Rights Act.

You should have asked – what is it that many Asian students do to succeed ? Everything else is dancing around on Kool Aid.

In this new environment the Asian students and their parents are the enemy. They work hard and demand nothing.

‘We began to talk about Whiteness and the three I’s of racism (institutional, interpersonal, and internalized). It was hard, and there was discomfort, there were tears, there was pushback.’

–Sounds just like the Communist Chinese ‘re-education’ camps under Mao.

Ms. Friedman is assigned to PS63, I don’t know why she admitted that important information from her article:

https://www.staracademyps63.com/school-leaders

I disagree. Asian students are not even aware of the subtle forms they experience to succumb to whiteness. For example, instead of using their given name, they give anglo names to teachers. I’ve read beautiful books like My name is Yoon because I want them to feel a sense of pride in their identity. Black and Brown people have their history here in the states and so do Asians. But there is an omission of history, purposely so people cannot see the similarities in the U.S. experience. There’s also a misconception that Asian students don’t go through cultural identity crisis and that all Asians are successful academically. I’ve had Asian students and even colleagues who have shared that they felt their families see them as unsuccessful for choosing professions or colleges that were not white collar, Ivy League like schools . The issue is that Asian families feel omitted from the conversation and therefore consider themselves as the enemy. I could understand. But to use stereotypes to add to the disrespect of another group because of that or compare groups of people

Is unfair and solves nothing. I know that, China has. Had the longest formal educational system in the world with a focus on. Math first. The high stakes of passing a test just to get into college that forces poor ppl to sacrifice for that better life, that is carried over when they arrive here. I respect it and understand it and it’s just a small part of my own learning in trying to understand differences. Black and Latinos were colonized and oppressed by Europeans for centuries. Their experiences are based on institutional racism that made sure they couldn’t get an education and it wasn’t until the civil rights movement that we began to see access happen and still not in an equitable way. That was only in 50’s. There are many Black and Latino students who also try their best. Depending on the countries Latinos come from, and social class, their educational experiences they come with are also different. But it doesn’t mean the U.S. educational system has got it right. it’s not about getting the educational system here to stop oppressing our students and start giving them what they all need.

You can talk and talk about race forever but that doesn’t change the fact that the NYC school system is only 15% white. So how can whites be the problem?

NYCDOE stats – https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Education/2018-2019-Demographic-Snapshot-by-Borough/uh2w-zjsn

That’s a fair point, but don’t oversell it: 15 percent of the DOE is 170,000 kids. That’s 94 white kids for each of the district’s 1800 schools — not that you’d split them up like that, but there’s still a bit of diversity to go around.

I thought this was about the effect on education gaps? It seems Asians are being discriminated for achieving? How does that make sense? Does that not point to a family culture problem in community for lack of achievement? White Appalachians have the worse education problems, is that racism?

Pingback: What Happened When One NYC School Decided to Really Talk About Race – Alexia and the Library

Thank you Ms. Friedman for addressing this issue. it is one of the most important topic that you can discuss.

How many Black|Brown teachers are employed in your school? I hope you are able to continue exploing race issues in a meaningful way without falling prey to trite, pandering perspectives.

I honestly am tiered of this “white supremacy” nonsense. You know why Jews and Asians are successful despite being repressed and descriminated against? Because they don’t feel sorry for themselves and work hard! The majority of Jewish and Asisan parents are involved in their children’s education and their day to day lives.

Do you think any of this ‘anti-whiteness’ stuff will help? No. The students who aren’t successful at my school show up with Air Jordans, fancy smart phones and yet come without pencils. Their reasoning? “That’s your job. I am poor. You’re Asian so you’re rich. You pay for my pencils.”

My parents came from China. We were a family a five living in a two bedroom apartment. My parents made sure that we were doing our homework. How dare De Blasio! Reading this completely dismisses all of the hard work and sacrifices my parents made. Oh, and what about Holocaust survivors? My husband’s grandmother hid in the forests of Poland for three years during WWII and had 95% of her family murdered. She came here and had three very successful children. Do you think she had it easy? Yes, dismiss them as well. Dismiss the Irish who were also discriminated against. Ever seen those old photos with “Irish need not apply” signs? Well, I’d say they’re doing pretty well now. Why not read the book “The Jungle” by Upton Sinclair. Right, they had it so easy because they were white.

Why this obsession with race? Just study hard, get an education, get a good job and help other people once at the top. There is no institutionalized racisim in America. All this has been doing is making people hate whites and Asians. How is this our fault? Do your homework! Study! Work hard! Parents should show up to parent teacher conferences. Fathers shouldn’t abandon their kids. It has nothing to do with race. It has to do with lousy parenting and a self-pitying way of thinking.

My recommendation is you read up on real American History (and not the nonsense they make you study in schools that purports Columbus as the explorer who discovered America!)and Race Relations in this country and the root of systemic and institutionalized racism before giving your overly simplistic and offensive solutions. i always find beneficiaries of white supremacy will defend its inequities as long as thy are bestowed scraps of privilege even though they themselves are not white.

Again. You are blaming something or someone! That is the thought pattern that will get you the same location where you started. Everyone knows that Columbus didn’t discover America. I was even taught in school about that. Also, is really practical. Kids need to study to pass an exam. How long does an average student study?