Bronx District Attorney Darcel Clark testifies at a City Council hearing about the problem of low pay on both sides of the criminal courtroom.

At a City Council hearing last week, representatives from both sides of the criminal justice system found something they could agree on: the pay is just not enough.

According to Tina Luongo, attorney-in-charge for criminal practice at the Legal Aid Society, which handles the majority of the city’s indigent defense, the organization is suffering from a crisis of attrition and facing difficulty recruiting new lawyers. The same is true for the District Attorneys’ (DAs) offices throughout the city, said the Bronx and Staten Island DAs and reps from the Queens DA.

These organizations, which are responsible for the bread and butter work of the criminal justice system, identified a common set of problems: their attorneys are consistently saddled with student loan debt from costly law school, the exorbitant costs of housing and, for many, childcare in New York City. Under such financial pressure, they are leaving their poorly paid jobs as assistant district attorneys (ADAs) and public defenders, often for higher salaries at other government legal jobs.

“Just this month, six experienced Legal Aid Society staff attorneys left Legal Aid to become Office of Court Administration (OCA) Court Attorneys because OCA salaries are so much higher,” said Luongo.

“Over the past year, 105 ADAs left the office,” said Bronx DA Darcel Clark. “31 went to other city, state and federal Agencies. With 516 attorneys currently on staff, the result is an attrition rate near 20 percent.”

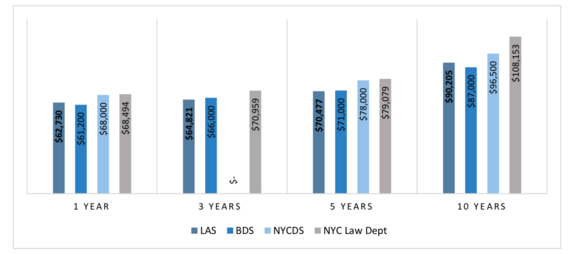

According to a report compiled for the Council’s Committee on the Justice System, the body that presided over the hearing, an attorney with three years of experience or more can be hired by the Administrative Trial Unit at the Department of Education with an annual salary of $85,000. A job for someone with the same experience at Legal Aid or the Manhattan DA would pay $20,200 and $16,000 less, respectively. Those disparities only increase as lawyers gain experience.

Testimony throughout the hearing painted a detailed picture of how these high attrition rates have serious consequences for the proper functioning of the criminal justice system. For one, they lead to a system staffed by less skilled and experienced attorneys and potentially worse outcomes on both sides.

64 percent of Staten Island ADAs have five years or less of experience, according to Staten Island DA Michael McMahon.

“I cannot stress enough the value that a veteran prosecutor brings not only to the courtroom in trying cases, but also in mentoring and guiding the younger staff to avoid mistakes,” he said.

“Experienced, savvy, committed assistant district attorneys are necessary to faithfully exercise their immense discretion and ethical obligations,” said Councilmember Rory Lancman, who chairs the Committee on the Justice System. Lancman will run for Queens DA in 2019.

“No government agency is ever going to be able to compete with the private sector—people understand that—but we shouldn’t be in a scenario where the Law Department or the Department of Education is attracting people away from vitally important functions in the criminal justice system,” said Lancman.

For defendants and defenders, consequences might be more severe—especially because public defenders are paid less than ADAs.

“Pay disparity in public defense disproportionately affects aspiring defenders from the communities that we serve,” said Shannon Cumberbatch, director of hiring, diversity and community engagement at the Bronx Defenders.

“It affects those from immigrant backgrounds, from racially and socioeconomically marginalized backgrounds. Individuals from these backgrounds are overrepresented in the court system and underrepresented in the court system as defenders. This is not because of lack of interest.”

Cumberbatch explained that these individuals are least likely to have family support to fall back on—something many public defenders testified was necessary, in their experiences—and more likely to need the financial stability of a higher paying job. As a result, we get a system where the public defenders do not share experiences with the clients they represent.

McMachon echoed this sentiment. “Our recruitment pool has dwindled to lawyers who come from personal wealth, law school graduates who have struggled to find other employment,” he said.

In a final session, many public defenders testified about personal hardships they have experienced as a result of low compensation. They also emphasized that as public defenders, they are generally paid less than prosecutors, and argued that this disparity reflects the low value placed on their work and relative bias towards prosecutors.

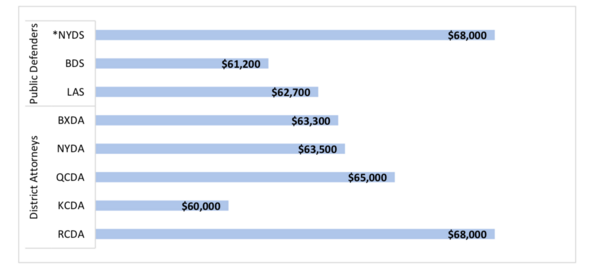

According to the committee’s report, starting salaries at every DA office but Brooklyn’s are higher than the starting salary at Legal Aid. In addition, a Legal Aid lawyer with 3 years of experience makes $11,200 less than an one at the Staten Island DA and $4,700 less than one at the Manhattan DA.

“There’s no other greater evidence of the lack of balance in justice when the pay levels are [unequal]. It’s just a clear statement that we value this work less than that work,” said Councilmember Andrew Cohen.

Turnover also has major financial costs for these organizations: :ost productivity and duplicative reassignment of cases cost the Bronx DA an estimated $3.7 million this year, said Clark.

As prosecutors and defense both agreed on a shared problem, they also agreed on the cause: The money coming from the city is just not enough to pay more.

District attorney’s offices are funded through the city’s annual budget. Organizations that provide public defense services negotiate a contract with the city periodically. Legal Aid’s contract is in the final stages of re-negotiation with the Mayor’s OffIce of Criminal Justice (MOCJ) but Luongo says that their request for more funds to achieve salary parity is likely to be denied. That’s what happened last year when they requested $3 million for salary parity.

They just don’t have any leverage.

“Here’s the reality: We’re going to show up for our clients. The people who talked today who are under enormous personal financial hardship—with a broken furnace—[they’re] showing up to work,” referring to a Legal Aid attorney who testified that she couldn’t afford to fix her broken furnace.

In her testimony, Elizabeth Glazer—who leads the budget negotiation process for the city as the director of MOCJ—was hesitant to admit that retention of skilled attorneys was even a problem for DAs and public defenders. But as she was questioned by Lancman, Cohen and Councilmember Deborah Rose though, she yielded somewhat.

City Council

A chart prepared for last week’s hearing shows starting salaries at public defender agencies (New York County Defender Services [NYDS], Brooklyn Defender Services [BDS], Legal Aid Society [LAS]) and District Attorney offices (Bronx [BXDA], Manhattan [NYDA], Queens [QCDA], Brooklyn [KCDA] and Staten Island [RCDA]).”

“I guess in an ideal world we would have perfect salary parity across many different aspects of the profession,” she said.

Glazer characterized the disparities between ADAs, public defenders pay and salaries at other agencies as a product of a complex historical system and political process.

But when pressed why salary parity wasn’t a baseline issue in contract negotiation, Debbie Grumet, MOCJ’s budget director, testified that it simply isn’t a priority. The primary metrics that determine contracts between the city and indigent defense providers are anticipated caseloads and anticipated non-legal services to be provided.

The solution appeared quite simple for most everyone else in the room. “We could say we’re not going to contract with you unless you pay them ‘X’,” said Rose.

“Pay the public defenders of this city the same salaries as Corporation Counsel,” said Luongo, referring to the office of lawyers that represent the city.

That’s the fast route, though Lancman has introduced a bill that would create a task force to address the issue of pay parity over the coming years with the goal of introducing a report that outlines strategies, legislative or otherwise for mitigating the issue.

“The priority is less the bill than it is the issue,” he said, however. “The next step is the resolution of the contract.”

City Council

This chart compares salaries over a career at public-defender agencies Legal Aid Society, Brooklyn Defender Services and New York County Defender Services with the city’s Law Department.

City Limits is a nonprofit.

Support from readers like you allows us to report more.