nyc dcp

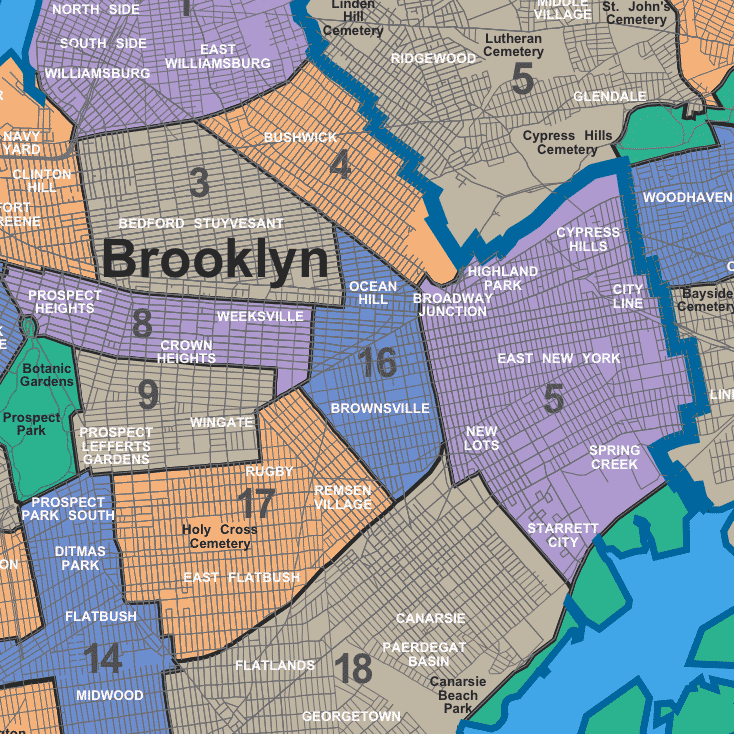

A map of community districts on the Brooklyn-Queens border. Fair-housing advocates have sued to end a city policy that gives residents of a particular district 50 percent of slots in new affordable housing built there.

A little over a year ago (August 17, 2017), one of the authors wrote an opinion piece for City Limits Magazine entitled, “Missing the Target on Segregation.” It was written from a community development perspective and made the argument that to disagree with community preferences (let alone sue over them) without “a countervailing demand that the city affirmatively, deliberately and aggressively seek to rezone and finance new construction of affordable housing — affordable to the very people being displaced elsewhere — in low rise, affluent (and yes) White neighborhoods is the height of irresponsibility.”

It was readily admitted that the current community preference policy was not rational, but maintained that “to exclude people from opportunities for improved housing in the very neighborhoods that were the only neighborhoods that they were permitted to live in for generations does not only belie arguments made on fair housing grounds, but represent a modern day racist approach to housing redevelopment, not unlike the racist approaches of racial zoning, restrictive covenants, redlining and urban renewal.”

These were very strong words based upon very strong sentiments — sentiments that we now believe may be over-stated and missing the point.

About a month after that article was published, we were invited by Enterprise New York and the Fair Housing Justice Center (FHJC)—along with many others from the affordable housing, supportive housing, legal services, human rights and fair housing sectors—to participate in what was billed as an Affordable Housing & Fair Housing Regional Roundtable. The impetus for this collaboration was a 2015 lawsuit (Winfield v. City of New York), which challenged the city’s Community Preference policy—a policy that gave priority for apartments to local residents for 50 percent of the new apartments being offered for leasing. The lawsuit, brought by three Black lottery applicants for a project in Manhattan, claimed that the local preference policy furthered segregation and violated the Fair Housing Act. The Manhattan neighborhood they applied to live in is predominantly (approximately 70 percent) White. The goal for the proposed collaborative effort was to provide a forum for education and discussion targeted towards mutual agreement on how to reconcile Fair Housing/Anti-Discrimination policy with local efforts to counter gentrification and displacement within New York City communities of color — those communities almost exclusively targeted for rezonings and massive “affordable housing” development under the current mayor’s 10-year housing plan.

The first few meetings were somewhat tense, to say the least. At an early meeting, one of our community development colleagues stated that if the Fair Housing justice community wants dialogue they should drop the lawsuit. From the Fair Housing justice side, responding to a comment about how community preference was necessary to protect the very people the Fair Housing Act of 1968 intended to protect, it was stated that anyone who is in favor of community preferences was against civil rights. It seemed the battle lines were being clearly delineated.

But this has not been the case. With excellent staffing support from both Enterprise and the FHJC, and the assistance of Bennett Brooks, Senior Mediator at the Consensus Building Institute, our monthly general meetings and interceding committee meetings have been civil, informative, sensitive, and collegial. And although no definitive consensus has been reached, those of us with an urban, mostly New York City perspective, better understand the challenges of working for housing justice in suburban areas, where Home Rule prevails and where the only housing that can be built as of right are single family homes. This, of course, discourages the development of higher density, affordable housing.

This dilemma is exacerbated by the need for environmental reviews to accompany any discretionary action by local authorities. Oftentimes, these reviews provide ready excuses for refusing permits on the grounds of insufficient infrastructure, over-crowded schools, traffic concerns, air quality, noise, and the like. Also, there has been the stark recognition that community preference in White suburban areas means continued White exclusivity in these same neighborhoods. We even heard stories about preference guidelines that were so restrictive (to keep out minorities) that they had to be revised several times in order to fill the development.

On the Fair Housing side, there is a growing appreciation for the dilemma faced by those of us who develop supportive housing. Even admitting that community preference is not rational and even arbitrary in terms of targeted geography and targeted beneficiaries, the actual preference is often the only leverage a supportive housing group has to get community board approval for one of its projects. This is due to the pervasive position of nearly every community in New York City that maintains that they already are “over-burdened” and have done more than their “fair share” for the purpose of addressing public needs—particularly housing the homeless.

We would say that there is even a recognition of why those of us in the community development sector believe that people for whose benefit the Fair Housing Act was passed are being hurt by a one-sided application of Fair Housing laws focused on de-segregation. This is because people of color are being displaced—from formerly redlined areas that were depressed, disinvested, and partially destroyed—at the time when these same areas are now becoming neighborhoods of opportunity due to the infusion of public and private investment. In other words, without a local preference, and with Fair Housing requirements that force developers to advertise units in outside areas, including White-dominated neighborhoods, an implicit preference is being given to Whites who, by moving in, would accomplish desegregation, albeit perhaps at the expense of housing opportunities for local residents of color. Of course, this is exacerbated by recent city policy preserving the low rise character of many predominantly White New York City neighborhoods, even down-zoning them.

But in a recent discussion, some very basic assumptions of our sector were challenged—again, in a very respectful and collegial manner. We were asked about our main concern. Were we concerned with simply favoring one set of people over another—even if in the name of restorative justice? Or was our primary concern displacement?

Acknowledging that for most of us the primary concern was displacement, we were asked if we had access to data that demonstrated that the community preference system was actually benefiting those most at risk of displacement. We did not. Furthermore, we were asked if there were other ways of fighting displacement that may be more effective than a community preference. This led to a discussion of current city affordable housing programs that, some would argue, does not do enough to serve residents most at risk of displacement and homelessness. Others present called for specific reforms to the current rent stabilization law, which enables landlords to utilize vacancy increases and other legal means to systematically move apartment rents beyond the reach of local residents.

It was left as an open question as to whether this issue of community preference should be that which divides our sectors, or, given our main concerns regarding displacement, local family/community disruption, and homelessness, if perhaps the community preference issue is little more than a red herring that is obfuscating and preventing constructive collaboration. This is where we are at this point in our year-long effort and we look forward to ongoing discussions.

In closing, at this time, our most basic message to our colleagues in the community development field is to keep an open mind. This effort will soon expand to the larger universe of stakeholders whose sectors are currently represented at this roundtable. We look forward to continuing this discussion and anticipate an enlivened, informed and successful public summit sometime this fall.

Harry DeRienzo is the president of Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association. Kirk Goodrich is the director of real-estate development for Monadnock Development. Ismene Speliotis is the executive director at MHANY Management.

12 thoughts on “CityViews: Affordable-Housing Advocates Must Listen to Opponents of Community Preference”

The Community Preference is designed to enable people to remain in their own neighborhoods if they so desire. The preference also builds support for these projects among local residents. Nothing wrong with either of those goals.

In gentrifying areas, long time residents are fighting to retain Community Preference because they hope it will reduce displacement. Fair housing advocates counter that community preference is used by white neighborhoods and towns to stay white. Underneath it all is structural white supremacy that forces us to fight over insufficient race-neutral policies when the real goal is to dismantle structural white supremacy. People on both sides getting together to discuss is clearly a first step in figuring out how we can do that. #undesigntheredline

White Supremacy? What are you talking about? NYC was only 33.307% white in the 2010 census, down from 34.980% white in the 2000 census.

NYC census demographics – https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Census-Demographics-at-the-NYC-Community-District-/5unr-w4sc

I’m not sure the numbers are really dispositive here. A white minority controlled South Africa for decades.

Name me a white-majority neighborhood with such a proposed housing project?

Where I live, Sunset Park in Brooklyn, there is no “both sides”. It’s at least three or four sides and when there is an actual hope for housing there more “sides” popping up every day.

“Of course, this is exacerbated by recent city policy preserving the low rise character of many predominantly White New York City neighborhoods, even down-zoning them.”

…recent? Bloomberg’s downzonings were bad, but they were following a century of precedent – the 1916 and 1961 zoning codes did the exact same thing, in a much bigger way.

Bloomberg downzoned large sections of the east shore of Staten Island in 2005/06. This followed years of bottom-up requests from local elected officials and community groups. In many neighborhoods large 1 family homes were torn down only to be replaced with attached 1 & 2 family townhomes which stressed Staten Island’s limited road, water & sewer and school infrastructure. Most sections were downzoned from R3-1 to R3X or from R3-2 to R3-1. The downzonings helped undo the mistakes of the 1961 zoning which permitted too many attached and semi-attached homes on an island that could not support them. In fact the 1961 zoning included large sections of R3-2 zoned blocks on the east shore. By 1962 that zoning was changed to R3-1.

no that is racial talk all people should be able to apply and get a apartment in any building affordable housing equaly not just because you lived in a neighborhood you said white neighborhoods use zoning to stay white other neighborhoods for instance farrockaway does the opposite this is all wrong stop putting everything into a racial zone all people should be mixed up together not everybody lived their whole life in neighborhood we the coalition of the rockaways want a mixture of the melting pot nyc is not segregated policies thank you

your wrong not only white neighborhoods do it all neighborhoods do it farrockaway Bushwick Brownsville eny Bronx all do it they should get rid of community preference in affordable housing because all people in nyc should equaly be able to get affordable housing we need a mix in our neighborhood coalition of the rockaways bruce Jacobs not just who politicians want to keep in their neighborhoods

NYC is under no legal obligation to build ‘affordable’ housing.

Community preference is very valuable in communities that were considered disadvantaged. In the Late 70’s when the South Bronx was burning and the landlords paid people to burn down the buildings for tax right offs, no one was concerned or even wanted any parts of these communities that were DEPRESSED, DISINVESTED, and DESTROYED, not even Mayor Koch. Now all of a sudden the community preferences rule is an issue, bullshit. The same landlords that paid to have the buildings burn downed are the same developers that want to claim there property back as of right. HPD should be held accountable for the assurance that the community preference meets the existing community, that’s FAIR, so that the current residents can have an option to stay in the community that they live in for decades now that developers want to invest, improve and displace current residents. If you want fairness it should involve all parties and stakeholders. Each Community Board should have a housing community member sit at the table when these applications are being selected so that the fifty percent preference is adhered to and not questioned. HPD WILL SAY OH WE CANT DO THAT , THAT WOULD VIOLATE PEOPLES PRIVACY. We are not interested in people privacy, just the ZIP CODES. That’s my opinion on FAIRNESS.

Community Preference policy could be a good thing and I support it so local residents benefit and can be protected from displacement. However, the flip side is it definitely can lead to further economic and racial segregation of NYC. There is no easy fix, however the best way to approach this is to ensure all affordable housing developments around the city are true mix income developments providing 50% of the units for low income, very low income and extremely low income and 50% of the units for moderate and middle income families to ensure community income is balanced which will lead to the long term stability of the neighborhood. there needs to be a balance between gentrification, community improvement and stopping concentrated poverty across the city.