Adi Talwar

Rubén Vasquez (47) working on a car at Vasquez Muffler located on 1275 Jerome Ave in the Bronx.

Ruben along with his brother Roberto and father Pilar have owned the business since 1993.

To the De Blasio administration, the Bay Street area in northern Staten Island represents a great opportunity for housing and commercial development. It’s in one of Staten Island’s most transit-rich areas and a block from the waterfront. It’s currently zoned “M” for “manufacturing,” which meaning industrial businesses can set up shop there, but no new housing can be built. The administration would like to change the zoning to allow mid-density residential development with commercial retail on lower floors.

But the Staten Island Housing Dignity Coalition, a coalition of community and faith-based organizations in Staten Island’s North Shore that has been organizing in response to the administration’s rezoning bid, is concerned about the plan—and specifically, about the effort to rezone M-designated land.

Their concern is twofold. One, they know that industrial jobs are often accessible to people with lower levels of education and pay more than jobs in the retail sector. Even though there are some vacancies in the Bay Street area, they know that losing any industrial space could mean permanently taking away the opportunity for such jobs.

Two, they know their community desperately needs more affordable housing, but they’re worried the city is giving property owners a windfall by asking for too little in return for the rezoning when it comes to requiring affordability, given that residential buildings result in far higher rents than industrial businesses. (In 2016, the new Urby Staten Island Apartments development asked for $3,310 for a two-bedroom apartment.)

“The return for the landlord is greater than the return for the community,” says Jose Lopez of Make the Road, a member of the Staten Island Housing Dignity Coalition.

While Mayor de Blasio indicated at the beginning of his term that he wanted to do more to protect industrial land than his predecessor, industrial land has been a significant part of the land targeted for residential rezonings. This is of concern to industrial advocates, who worry about the impact on the industrial sector and its workers and on the city’s own industrial needs. It’s a complicated matter for other neighborhood advocates, some of whom share the same fears, some of whom are worried about whether the administration is getting the right bang for the buck from property owners, and some who’d in fact like to see a more residential neighborhood.

And while the administration has been exploring some innovative ideas, like restricting non-industrial uses in certain areas, creating mixed-use buildings where space for an industrial business is required, or densifying industry by rezoning to allow multi-floor industrial buildings, there remain questions about the timeline or feasibility of those strategies and whether they’ll be able to compensate for the increasing scarcity of industrial land.

The administration, for its part, says it is striking a balance between promoting the development of housing in transit-accessible areas that can accommodate more density, creating space for growth in other industries that are thriving, and preserving the city’s industrial sector through careful study and investments.

Defining the industrial sector and its decline

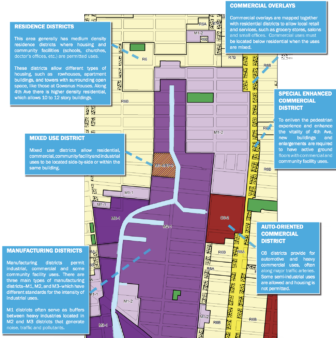

The city has three types of zoning districts: C for commercial, R for residential, and M for manufacturing. In the city’s M zones a range of industrial activities can be found, from manufacturing to warehouse and distribution centers to sewage treatment plants. There is also one kind of C zone, “C8”, where heavy commercial services like warehouses, automotive businesses, gas stations, and car washes are allowed.

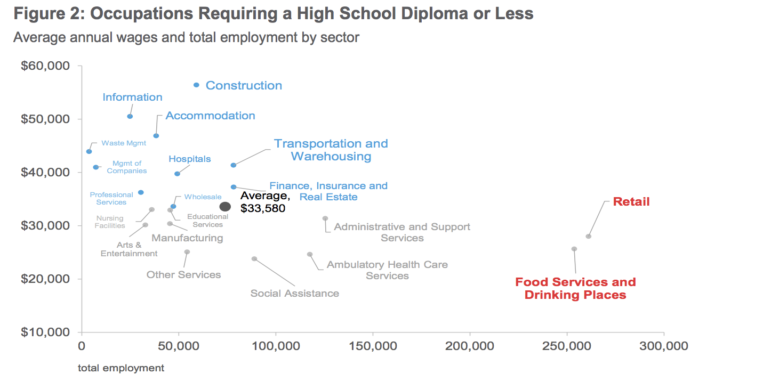

Industry advocates say the industrial sector is a crucial source of good-paying jobs for New Yorkers with less education. In New York City, according to the Pratt Center for Community Development, 58 percent of industrial workers have no more than a high-school diploma, and 58 percent make more than $30,001 a year, as compared to 33 percent of workers in the retail industry. (Pratt defines the “industrial and manufacturing sector” to include manufacturing, construction, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing, utilities, motion picture and sound production and recording, and waste management.)

Wages do vary within the sector: Construction jobs tend to pay the most, with average wages of roughly $55,000, while manufacturing jobs pay an average of $30,000. Wholesale, auto-repair, transportation and warehousing are in between. And required skill levels also can vary within each occupation: there’s a trend of newer, high-tech manufacturing companies employing workers with higher levels of education.

After the city’s major loss of industrial businesses following globalization in the mid-20th century, the mayoral administrations of Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg both believed that too much of the city’s land was zoned for industry and should be rezoned to stimulate residential and commercial development. Bloomberg in particular is known for rezoning large swaths of M and C8 land; the city lost about 4,050 acres of M land between 2002 and 2015, reducing the total percentage of land in the city that is zoned M from about 21 percent to 14 percent. C8 land was also reduced, such that by 2016 only one percent of the city was zoned C8.

Bloomberg can be credited with helping to encourage a new wave of “advanced manufacturing” through investments in the revitalization of properties such as the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He also created Industrial Business Zones (IBZs)—areas that he promised would not be rezoned, and where businesses could access special tax credits and other services.

But in those areas, and in all M zones in general, industrial businesses have seen growing competition from hotels, office buildings, self-storage facilities and entertainment venues—all of which are also allowed in M zones. As reported by Eli Rosenberg in NYCurbed, the increased scarcity of industrial areas and rising prices for those parcels that were left were particularly difficult for the kind of industrial companies that depend on large swaths of cheap land.

Industrial advocates believed they had an ally in incoming mayor Bill de Blasio, whose campaign materials said he believed “manufacturing 2.0 can be a critical part of the city economy” and that he’d “build on existing programs to preserve the physical integrity of Industrial Business Zones, stop illegal conversions of industrial areas, and support better infrastructure and workforce development planning” among other efforts.

But De Blasio’s neighborhood rezonings have targeted M and C8 land throughout the city.

De Blasio’s rezoning record

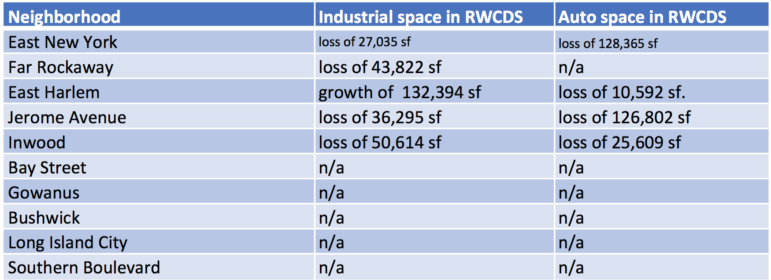

Though the city doesn’t analyze how many square feet of M or C8 land will be lost in a rezoning, it does provide a scenario (though the record shows the projections aren’t always reliable) of what kind of buildings might be constructed on sites that are likely to be redeveloped. In four out of the five rezonings that have entered the public review process so far, the city projects there will be a reduction of industrial space, and in four out of four rezonings where calculations were done, the city projects a loss of auto-related space.

Chart indicates the projected loss or gain in industrial and auto-space according to the city’s “Reasonable Worse Case Development Scenario” (detailed in the Environmental Impact Statement). Column three indicates the projected loss or gain in auto-space. N/A means a calculation was not given or an Environmental Impact Statement has not yet been completed.

The one exception appears to be East Harlem, where the city’s analysis actually projects a large increase in industrial square footage. The majority of that rezoning area was already residential, and the rezoning also requires non-residential uses on Park Avenue.

De Blasio, like his predecessor, can be credited for making investments to stimulate the city’s industrial properties, such as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the Brooklyn Army Terminal, or in Hunts Point where the city is in the process of developing and renovating space at a food distribution center. The administration also notes that the Industrial Development Agency, which provides tax incentive programs to spur business growth, has also closed on seven industrial projects this fiscal year. The city has also proposed the Long Island City Innovation Center, a mixed use development on public land that will include both light industrial space, commercial space and housing (though the project has its critics).

But Leah Archibald, executive director of Evergreen, a nonprofit that supports the industrial sector in North Brooklyn, say the rezonings throughout the city will “driv[e] the price up for the manufacturers that are here. It’s simple economics … They simply cannot afford to scale up with the real-estate costs that are so high.”

Adam Friedman, executive director of the Pratt Center for Community Development, notes that because Bloomberg already targeted much of the city’s waterfront real estate for rezoning, now de Blasio is rezoning areas deep within the boroughs. At some point the question is not only about jobs, but about whether the city has enough space to meet its industrial needs, he contends.

The Department of City Planning (DCP) points to the city’s growing population and says it’s choosing areas for rezoning that are near transit and can accommodate more population density than they do currently. The agency also argues that this is the best way to increase the supply of housing without knocking down housing in existing residential areas.

Furthermore, while recognizing that some industrial businesses are critical to the city’s economy, DCP argues there must also be space to grow the city’s other sectors, particularly those that are thriving. DCP notes that there are other sectors that can provide good wages to people without a four-year college degree and are growing faster, like professional, technical and scientific services as well as finance, insurance and real estate—office jobs, in other words. Many of the rezonings would result in both an increase in lower-paying retail as well as office space, according to the city’s predictions.

Would the industrial sector be growing faster too if it didn’t face so much competition for real estate? From DCP’s perspective, the city’s real estate environment is one of the factors that impacts growth, but competition from outside the state and country is also still an issue.

DCP

From the Department of City Planning’s Info Brief: Middle Wage Jobs in NYC

Varying responses in neighborhoods

Neighborhoods have reacted to the de Blasio administrations’ attempts to rezone industrial and auto-zoned land in different—and not always unified—ways.

In the western Bronx, the city’s effort to change Jerome Avenue from an auto-zoned corridor to a residential and commercial corridor sparked fierce controversy. Some community board members supported the change, saying it would improve quality of life in the neighborhood, while members of the Bronx Coalition for Community Vision contended it would displace businesses that employ immigrant workers. The Bronx Coalition took issue with the city’s description of Jerome Avenue as containing a number of “underutilized sites,” and argued that the city saw auto-shops “through the narrow lens of unused FAR and potential for building large scale residential complexes.”

In Inwood, the Economic Development Corporation and a coalition of residents who support an alternative community plan appear to agree on the need for a mix of new residential and industrial zoning on the blocks east of 10th avenue, but disagree on the details of how and where.

EDC would like to change the M-zoning at the tip of the island, an area mostly consisting of parking lots, to a higher density M-zoning in order to encourage a tall non-residential facility like a hospital. The supporters of the Uptown United platform, meanwhile, would rather rezone that area for housing in exchange for decreasing the heights of apartment buildings in EDC’s plan overall. They have also advocated to keep another area zoned M to ensure existing wholesalers and auto-shops are not displaced.

Some Inwood stakeholders also took issue with the city’s characterization of industrial and auto-businesses in the area in the city’s environmental impact statement for the rezoning. That document said the wholesale, warehousing, light industrial, and automotive businesses that might be displaced were “not of substantial economic value to the City, in terms of importance to the City’s overall economic activity; they can be relocated elsewhere in the City; they are not subject to regulations or publicly adopted plans to preserve, enhance, or protect them; and they are not a defining element of neighborhood character.”

As Make the Road’s Lopez articulates, even when residents are willing to accept a rezoning of industrial land, they may not always agree on the terms.

The city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy requires developers in a rezoned area to provide 20 to 30 percent of units at the same below-market rates, regardless of whether the property was rezoned from manufacturing to residential, or from a lower density to a higher density residential designation. That’s a great deal for owners of what was once M-land, who receive the benefit of a much larger percentage increase in the number of apartments they can construct, and on land they probably bought for cheaper.

Some community advocates would like to see the administration require more affordability in exchange. The Department of City Planning, however, insists that Mandatory Inclusionary Housing is not a policy meant to extract the maximum amount of dollars that can be squeezed from a project, and that such a policy would be prohibited under state law.

Ultimately, says Elena Conte of the Pratt Center, it can sometimes feel like the mayor’s rezoning studies are so focused on boosting unit count to meet the mayor’s affordable housing goals that they’re unable to undertake “actual planning and balancing.”

But the city says it’s quite committed to that balancing act.

Manufacturing new policies

To evidence its commitment to the industrial sector, the administration can point to its 2015 10-point industrial action plan. Some advocates, however, feel the de Blasio administration has been slow to roll out some of the commitments made.

In particular, the city promised to create restrictions on the construction of hotels and self-storage facilities in IBZs to preserve more space for industrial and manufacturing businesses. Restrictions on self-storage facilities passed into law in December. As for hotels, the city expanded the study to include not just Industrial Business Zones but also other M-zoned land. The city is on schedule to release an environmental analysis on the restriction this spring.

The city also launched a $150 million Industrial Development Fund—with $90 million in private funds and $60 million in public funds—to finance industrial real estate projects. Industrial advocates say accessing the funds is a difficult process, however: As of January, only one project had been approved according to Next City. (The Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development and Citibank have created another fund, the Urban Manufacturing Accelerator Fund, to help nonprofit developers access the Industrial Development Fund.)

The 10-point plan also talked about creating “new models for flexible workspace and innovative districts” to “bring a mix of light industrial, commercial, and limited residential development to appropriate locations in a way that supports 21st century businesses and 21st century jobs,” beginning with a study of industrial land in North Brooklyn. The city is exploring creating a mandatory mixed-use model where there would be commercial office space—or even residential apartments—on some floors, with a required amount of manufacturing space on lower floors. While there’s been one example in Williamsburg of such a project, the North Brooklyn study is still yet to be released.

These delays create some nervousness in industrial neighborhoods targeted for a rezoning. Take East New York, where the city’s plan included rezoning Atlantic Avenue as well as parts of Liberty Avenue from M and C8 to allow for residential growth. While community advocates worried about the lost of industrial land, the city said such businesses could be concentrated in the nearby East New York IBZ.

In a study of that IBZ, the city recognized that vacancy rates were low, at 5 percent, but promised to follow through with a range of strategies, including restricting self-storage facilities and hotels, and exploring a rezoning that would keep it M-zoned but allow multi-story industrial buildings in order to create more industrial space. With these and other strategies, the city promised the creation of 3,900 new jobs and 2.7 million square feet of new space in the IBZ.

The city has indeed allocated $16.7 million to improve infrastructure and public properties in the IBZ—the renovation of an underutilized business incubator is in the design stages—and has provided $60,000 to help the BID improve marketing and advertising of its businesses and real estate. But now a hotel is going up in the IBZ, and in the past five years about a dozen self-storage facilities have opened on M land throughout the neighborhood, further reducing space for industrial businesses, says Bill Wilkins of the Local Development Corporation of East New York. He says given the dwindling amount of M land in the neighborhood, use restrictions needed to be put into law immediately.

Wilkins also worries that densifying the IBZ will be difficult, and not feasible without significant financial incentives from the city. “It becomes a business challenge to build up, because owners might not have the skillset to build up, and there’s significant debt that goes along with that…and a lot of banks, they don’t want construction financing like that,” he says.

A 2016 Pratt report by Conte and Friedman reached similar conclusions. “When we initiated this study, we assumed that increasing density in the IBZs was an obvious, necessary, and viable option for providing space for industrial jobs,” they wrote. “By the time we completed this analysis of each of these neighborhoods’ industrial profiles …. we realized there would be significant obstacles”— ranging from the cost of developing multi-story industrial spaces, to the reality that while a second- or third-story space might work for an advanced manufacturer, other kinds of industrial businesses (like a wholesaler or auto-repair shop) need to be on the ground floor. They also emphasize that increasing the density of an IBZ must go hand in hand with restrictions, or risk inviting more hotels.

In an e-mail to City Limits, EDC stressed ongoing efforts to strengthen the restrictions on hotels and self-storage facilities and to bring high job density industrial uses to the IBZ.

In Gowanus, another M-zoned neighborhood with a rezoning study underway, the story is different, but also one where it’s unclear which policies to protect industrial space will move forward.

There, industrial advocates have actually made a request for more industrial density in the Gowanus IBZ to allow multistory industrial buildings, but the city has said it’s not within the scope of its rezoning study. There’s also discussion between the city and stakeholders about implementing some kind of mandatory mixed use model, but there are ongoing questions about how much M land should be rezoned in this way, and whether the model will work. Industrial advocates say that the model needs to be paired with oversight by a nonprofit dedicated to protecting industrial space, and also that the city needs to be willing to demand a higher percentage of space be set aside for manufacturing than was required for the first model in Williamsburg.

DCP

A diagram of zoning districts created by the Department of City Planning. Purple indicates M zones. The Gowanus Industrial Business Zone, which begins south of 3rd Street, will not be rezoned.

DCP is, in fact, aware of the various challenges and says it’s considering them carefully—from what kinds of industrial businesses would be able to occupy multi-story buildings, to the economics of sustaining a mixed-use building with a required industrial component—and that this in fact accounts for the slow roll-out of its North Brooklyn Industry and Innovation study.

One of its concerns is that it would rather not encourage a model that will end up not being economically feasible or rely on public subsidy, as it would rather invest city dollars in publicly owned assets like the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where the city has more control over the property.

The balancing act

While all parties may claim to be seeking a balance between housing growth and industrial jobs preservation, there will likely continue to be disagreements about just how and where that balance must be struck.

Make the Road’s Lopez is involved not only in the Bay Street rezoning discussion, but also the one in Bushwick, where a steering committee of community stakeholders is crafting their own rezoning vision for the neighborhood. In their own community plan, they’re making it clear: They deeply value their M zones and aren’t giving it up unless the city requires deeper affordability.

But at a meeting in February, as first reported by The Village Voice, community members met with city planners and were told that the city did want to rezone some manufacturing areas and didn’t intend to impose any additional affordability requirements.

According to the Voice, the city envisions “reserv[ing] about half of the neighborhood’s existing manufacturing space while also adding affordable housing and increasing buildable manufacturing space by 40 percent overall.” It wasn’t clear by press time which strategies the city intended to use to increase buildable manufacturing space.

Lopez says community members were deeply disappointed by what they’d heard.

“As a community, we’re pretty serious about not wanting to talk ‘M to R’ unless it meets our principles.”

Google Screenshot

Bay Street in Staten Island

4 thoughts on “With De Blasio Rezonings, City’s Scarce Industrial Land Becomes Scarcer”

Pingback: Jerome Avenue Rezoning Will Cost The Bronx Over 100,000 Square Feet of Auto Related Businesses - Welcome2TheBronx™

Huge storage facilities and hotels are a problem in IBZs. Also IBZs tend to make some communities, i.e. South Bronx, a permanent dumping ground for dirty energy, waste related and trucking intensive businesses.

The Mayor should expose Cuomo’s southern South Bronx shoreline dumping ground- the Harlem River Rail Yards- a NYSDOT property leased for 99 years to donor Francesco Galesi- as beyond almost any realm of transparency or local good.

Here’s a list of every ‘M’ zoned parcel in NYC, note how many residential properties of all types are located in ‘M’ zones-

https://files.acrobat.com/a/preview/a0a7b321-c4b2-4b15-a0a1-d213b96e3003

De Blaiso’s first Gowanus rezoning whet through in 2009 when he was the local councilman. It was a two block area along the banks of the industrial canal, next to the historic Carroll St Bridge. De Blasio and Bloomberg were in lock step on rezoning this and all Gowanus.

The new zoning was “Mixed-Use”, appeasing the local businesses that saw the business evictions that underway in order to make way for the “new.” That property is now built full out, 100% residential, with some like a small yoga studio to claim the use is mixed.

The vision these politicians, and the developers that fund their careers, have for the people of this city, isn’t one where we work and create things to meet our needs locally, but one where we all must look to Amazon and the UPS delivery for our needs. These new spaces which we are asked to aspire to live in, the new buildings the developers are putting up sure are clean and new, but also isolated, especially from the natural world around us. These proposed tower developments in the industrial areas don’t engage residents with the community and outdoor space Brooklynites are accustom to with row-house and street front stoops. They don’t allow for the sustainable living that the old row-houses provided. And then they also dismantle the adjacent residential row-house communities after they supplanted the industrial land that once supported them with jobs and goods.