CB4

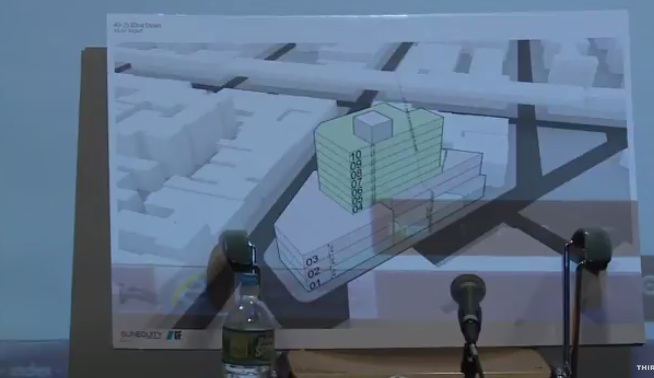

The proposed development as displayed at last week's Queens CB4 meeting.

Last week at Queens’ Community Board 4, which represents the polyglot, predominantly working-class immigrant and African American neighborhoods of Elmhurst and Corona, a developer was demanding a rezoning, and threatening an unpopular as-of-right development if they didn’t get it.

The lot in question was the site of a historic movie theater, known in its final iteration as The Jackson Tri-Plex. After it closed, the real estate investment trust Sun Equity Partners and developer The Heskel Group bought the ornate building and hastily demolished it, along with a popular neighboring grocery store. As one resident pointed out at the community board meeting, Sun Equity’s website advertises that their strategy “pinpoints underperforming assets and unique value-added opportunities,” which is apparently how they see this lot at the center of the neighborhood’s bustling immigrant-owned small business cluster. Now they want to build a Target on the site, with a big commercial, residential and community complex above it.

The packed community board meeting started with a presentation from the developer’s lawyer, who explained that they are requesting a spot upzoning which will allow them to almost double the amount of residential capacity on the site. Doing so would trigger the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) law, which sets affordability standards for a portion of new housing on upzoned lots. The developer’s representative, of course, presented this rezoning as a positive for the community, since the lot’s current zoning does not require any affordability.

There are, however, some major problems with this proposal. First and foremost, nobody wants a Target. Even if you believe that every neighborhood deserves a big box store, there are two malls on nearby Queens Boulevard, and one of them already has a Target. The store would add to the growing corporate chain presence on 82nd street—the only street in the neighborhood with a Business Improvement District, which residents call “calle corporate”—and would threaten the viability of neighborhood small businesses. On top of that, Target’s lease rider prevents the owner from renting the building’s remaining commercial space to any competing businesses; since Target sells just about everything, that’s going to be a problem. As another testifier pointed out, the rider even excludes thrift stores and laundries—two services Target doesn’t provide.

Second, the idea that triggering MIH makes this rezoning some sort of salve to the affordability crisis is a cruel joke. The most common criticism of MIH is that the “affordable” units are unaffordable to neighborhood residents. That’s certainly true. In my own writing, I’ve mostly focused on the impact that adding additional market rate development capacity will have on neighborhoods targeted for gentrification. But this rezoning points to another absurdity in the law.

The developer is proposing to use what’s called “option 2” of MIH, which requires the owner to set aside 30 percent of their units (in this case 27 apartments, all studios and 1-2 bedrooms) at an average of 80 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI). The word “average” is crucial here, because it implies that the developer will provide a range of options, which might look as follows.

- In the best-case scenario, there would be just 9 new apartments for the typical neighborhood household, which makes something like 40 percent AMI. This also means there would be nothing for half the people of Elmhurst—the poorer half that is most likely to face displacement.

- 9 apartment seekers would get homes at 80 percent AMI, and pay close to the median asking rents for market-rate apartments in the district. This means that wealthier-than-average people will get average priced apartments, and it will be called “affordable housing.”

- Another 9 wealthy but inexplicably ill-informed households might take the 9 apartments offered for 120 percent AMI, which amounts to prices above the neighborhood’s average asking rent. For some reason, people making 3 times the neighborhood median income are expected to move in and pay more than market rates for so-called “affordable” housing. Perhaps the developer assumes they’ll be willing to pay more in rent for the privilege of living above a Target.

This rezoning is very unpopular in the community. It is being fiercely opposed by groups like Queens Neighborhoods United, which successfully fought a proposed BID expansion over the past several years.(Full disclosure: I was a member of the group when I lived in Elmhurst). The only alternatives the developer is presenting, however, are worst possible scenarios for as-of-right projects on the site.

Sure, the current zoning would allow for a smaller commercial space that matches life on the block; in fact, a two-story building with six small ground-floor commercial spaces is exactly what the developer first proposed before they were requesting a rezoning. (Renderings of that less intrusive project are still buried on the developer’s website.) The current zoning would also permit a bigger building that’s 47 percent dedicated to community facilities, but that’s not what the developer is proposing.

Instead, at the community board meeting the developer’s lawyer presented an as-of-right model of a big, ugly blob of a building. The site layout would be a logistical disaster, compounded by the fact the site sits across from a busy hospital with ambulances coming and going at all times of day and night. The developer says they won’t build a hotel on the site, but reminded the board that they could. The implication was clear: the developer was using their as-of-right horror show to coerce the neighborhood into accepting an equally harmful rezoning.

At worst, the developer’s pitch had all the elegance of a ransom note during a hostage-taking: Give us what we want … or we’ll do something you want even less. At best, it manipulated the power dynamic between property owners and the communities impacted by their profit-making. Either way, it was nothing new.

In fact, the legal system is set up to allow these sorts of shenanigans. Developers can threaten the worst version of what the law allows in order to strong-arm planners into giving them what they want. Think of Donald Trump and the Bonwit Teller building: according to the late Wayne Barrett, when Trump wanted a rezoning to turn that department store into Trump Tower, he showed the City Planning Commission intentionally awful architectural renderings of the as-of-right possibilities, which included smaller floor plans than the store required. What’s notable is how similar this method is to the way the city has been rolling out rezonings of its own.

The mayor, his planners, and many city councilmembers have used the threat of untrammeled as-of-right development to sell upzonings in poor, predominantly people-of-color neighborhoods, as if these were the only two options facing our communities. Their proposition is that the city is growing, and luxury development is an unstoppable force that must be harnessed for the public good. Since communities will gentrify anyway, the theory goes, we might as well change the market calculus so that neighborhoods will get something out of the process.

In a recent conversation with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer, the mayor spelled out this argument. Referring to gentrifying neighborhoods that have not been upzoned, de Blasio claimed, “The scarcity of housing actually exacerbated the displacement. If you’re not adding to the supply, you have a pressured supply of housing, more and more people want to be there—of course that creates a massive displacement pressure…. If people think that no rezoning will just freeze paradise in place and everything is going to be wonderful, that is a fundamental misunderstanding of the last 20 years in this city.” This analysis begs a couple questions.

First, why upzone these particular neighborhoods? Why increase development capacity in the places with: a) significant stocks at-risk affordable housing; b) enormous rent gaps (the different between current ground rents and potential asking rents); c) high numbers of “preferential rent” tenants (precariously rent stabilized tenants whose landlords tenuously offer apartments at less than the legal maximum); and d) large percentages of low-income tenants who cannot afford even modest rent increases? Why not instead upzone wealthy, low-density but transit-adjacent neighborhoods, of which there are many? (According to a recent statement by City Planning Director Marisa Lago, the answer is political expedience.)

Second, when will they acknowledge that new development is not meeting a demand for housing, but rather a demand for investment vehicles? Recently released preliminary data from the triennial Housing and Vacancy Survey suggests that between 2014 and 2017, 69,147 new units of housing were built; during the same period, 62,854 apartments came off the market. In other words, the rate of apartments being used as safe deposit boxes, money laundering tools, pied-à-terres, and Airbnbs nearly matches the rate of new construction. The notion that the market can simply build itself out of the crisis requires us to ignore what the market is actually doing.

Despite these glaring flaws, city agents continue to press their style of upzoning as the only alternative to as-of-right development, which they rightfully assert is wreaking havoc in many communities. A politician like de Blasio, who would like to be seen as the country’s progressive champion, would never quote Margaret Thatcher, but his planning paradigm assumes one of her mottos: “There is no alternative.”

Whether it’s coming from predatory investors or “progressive” politicians, we must reject this coercive framework. There are, in fact, many ways to keep out the kinds of development that threaten working-class communities, and encourage the kinds that strengthen them. True, many of the best tools require federal and state action, but not all of them—the city’s land-use policies are ours alone, as are our choices around municipal public land and tax-foreclosed properties. In fact, this is why both city agents and local activists tend to focus on land use and public land as key sites of struggle—not because they are necessarily the best tools for every problem, but because they are the ones our uneven system of federalism and devolution has left us. At the very least, we can change the zoning in places targeted for destructive development—like the lot in Elmhurst—to keep out projects that will displace tenants and shutter small businesses.

The city will claim that such a move might constitute an “illegal taking” of private property, since it would restrict the amount of profit a landlord could make on a given parcel. Such claims, however, are often threatened but rarely litigated. The last time something like this came before the supreme court—when in 2011 an Upper West Side landlord decided that rent stabilization was an illegal infringement on his right to rent gouge—the Supreme Court decided the case did not merit a hearing. Fear of unfounded litigation should not be one of this city’s guiding planning principles.

* * *

At last week’s Queens Community Board 4 meeting, something remarkable happened. After the developer presented their demands, dozens of community members testified against the rezoning and against the developer’s as-of-right threats. (The only speaker who didn’t denounce the project was a member of SEIU 32BJ, who noted that the union was in talks with Sun Equities around property service jobs.)

When it came time to vote, the chair of the land use committee instructed the board that, while they might not like the options being handed to them, they should either vote for the rezoning or vote against it with very specific conditions that would lay out under what circumstances they would accept it. He offered that perhaps the board could vote no with the recommendation that the developer instead seek to use MIH option 1, which provides a smaller quantity of more-affordable housing.

The board, however, rejected this proposal. One member called out that it would mean tinkering with a project that they don’t want to see there at all—not the least because the Target store appears in both the as-of-right and MIH scenarios. Instead, the board voted nearly unanimously (24 for, 0 against, 4 abstentions) for a motion to oppose the rezoning with a recommendation to initiate a different rezoning that would prevent big box development and encourage smaller-scale local businesses.

The Community Board is trying to break out of the rezoning-as-ransom scenario. As the land use chair and board chair pointed out at the meeting, however, community boards’ land-use role is purely advisory; while they have the power to initiate a rezoning, they don’t have the power to enact it. For that, they need the support of their new city councilmember, Francisco Moya, who, conveniently, is also the chair of the city council zoning committee. To make that happen, there must be massive and ongoing community pressure.

Queens Neighborhoods United has already proven they are capable of such a campaign through their long struggle against a BID expansion along Roosevelt Avenue—a fight many thought they could not win—and they are committed to organizing around this new threat too. Communities across the city should look to this corner of Elmhurst as an example of how local organizing can push beyond the double-bind of predatory development and exclusionary upzoning.

Samuel Stein is a Ph.D. student at the CUNY Graduate Center who teaches Urban Studies at Hunter College. His book on urban planning and real estate will be published later this year by Verso Press.

5 thoughts on “CityViews: When Developers Threaten Bad ‘As of Right’ Projects, Rezoning Becomes Ransom”

I thought that spot rezonings weren’t legal.

That neighborhood needs a Target. A big bright clean store with reasonably priced items. Better than the dingy overpriced retail they have now.

Target has bad lighting that makes for inhumane work environment.

The concern is this will cause traffic congestion. Elmhurst Hospital, the only remaining hospital in the area can not have traffic jams that a Target with cause.

(More people residing within) the neighborhood decided that actually, they didn’t need a(nother) Target. If they did, then existing stores would’ve shuttered for lack of business and been replaced by better ones.