Abigail Savitch-Lew

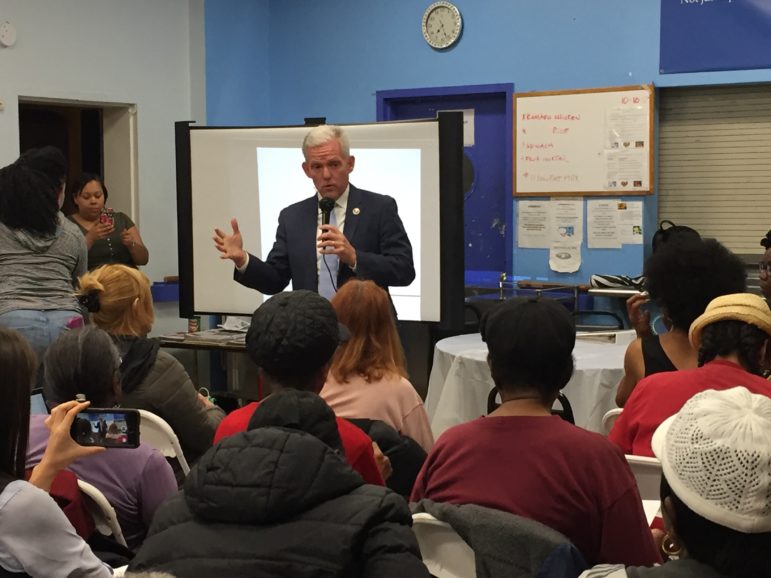

Councilmember and Majority Leader Jimmy Van Bramer addresses the Justice for All Coalition at Queensbridge Houses' community center on October 16, 2017.

On Monday night, City Council Majority Leader and local Councilmember James Van Bramer addressed a crowded room in the basement of Queensbridge Houses’ community center, promising them “whatever happens going forward, we will do it together.”

The “town hall” was organized by the Justice for All Coalition, an alliance of public-housing residents, labor and church groups that formed in April of 2016 in response to the news that the de Blasio administration would seek to rezone Long Island City as part of the mayor’s 10-year affordable housing plan. While the study has moved slowly and is still in a planning phase, the Department of City Planning has been hosting public workshops all summer and fall, a sign that it is gaining momentum.

Earlier rezonings have already completely transformed Long Island City. The once-industrial neighborhood ranked first among neighborhoods in the country with the most new apartments since 2010, according to a study by RentCafé. Since 2000, the neighborhood has become more White, less Black, and incomes in the area south of Queensbridge Houses have skyrocketed, according to a presentation by Paula Crespo from the Pratt Center for Community Development.

The Department of City Planning says its potential rezoning will correct the mistakes of Bloomberg-era rezonings in the area by requiring a percentage of affordable housing and creating mixed-use development, but Justice for All Coalition members are concerned that the rezoning will not bring sufficient benefits for low-income residents and could further exacerbate the area’s gentrification.

Over the past year, the Justice for All Coalition’s concerns have grown to encompass a number of other development ideas, including the proposed BQX streetcar that would connect Astoria to Sunset Park, the potential redevelopment of Sunnyside Yards and another nearby railyard on Jackson Avenue, and the city’s selection of TF Cornerstone to build housing (75 percent market rate), a school, commercial space, and a park on a public site in Hunters Point South.

The coalition, which could always pack a house, has also drawn more participants over time. Monday’s meeting was attended by individuals from the Queens Anti-Gentrification Project, Democratic Socialists of America, a new activist group formed after the presidential election called the Long Island City Coalition, Community Board 2 and the Artist Studio Affordability Project—all seeking to build bridges between the different communities of Long Island City and Astoria.

Van Bramer’s commitments

“You invited your elected officials, I am here,” Van Bramer told the crowd on Monday, explaining that he couldn’t stay for long because he had six other engagements that night. He stressed his devotion to public-housing residents—including the $150 million he said he had allocated to Queensbridge Houses—and his “humble roots,” several times pointing to a picture of his mother that was conveniently hanging on the basement wall. She had worked at a local Pathmark, and Van Bramer said his family had often struggled to pay rent. “I will never ever renege on that. And all of you are now a part of me.”

Van Bramer emphasized that prior rezonings of Long Island City had occurred before he was elected in 2009. As for the several projects proposed by de Blasio, “there are some merits to those projects and there are some things that people are concerned about.” He emphasized that “all of them are proposals, they’re just ideas, I have not approved any of them” and that his aim would be to ensure “that public housing remains strong and affordable, and that we actually check the growth and make sure that this isn’t the wild west when it comes to building luxury housing,” with adequate investments in good jobs and transportation.

During the question and answer session, Van Bramer repeated his promise to become the prime sponsor of the Small Business Jobs Survival Act once current prime sponsor Annabel Palma is termed out, and to try to pass that legislation. (Some councilmembers have said they have stopped pushing for the bill due to questions about its legality.)

He also promised that if NYCHA ever tried to develop its open spaces with more housing—what is known as “infill development”—he would say to NYCHA and the mayor “Don’t even think about it. Don’t even think about it. Don’t come here. We’re going to keep public housing public housing.”

NYCHA is using infill development in other areas of the city to raise revenue for its deteriorating public housing stock. The majority of sites entail 100 percent below-market housing, but some sites will also have half-market rate, and half below-market housing. Despite rumors to the contrary, the administration has no intention to tear down existing public housing or hike rents. Yet some public housing residents still have concerns with a real basis about how they will be affected by rising costs of living as neighborhoods change around them, and residents have also been subject to federally imposed rent increases (up to the limit of 30 percent of family income) in recent years.

Van Bramer an ally?

Van Bramer’s remarks were greeted warmly and with significant applause by many public-housing residents, and organizers were pleased that he had witnessed the size and strength of their group.

Prior to Monday, Van Bramer has met with group members in his office and attended a protest organized in June, and a member of his staff has attended the coalition’s monthly meetings, according to Justice for All Chairperson Sylvia White. White said that at the protest, Van Bramer promised to support the group going forward, and she decided to take him up on his offer and invite him to a town hall. On Monday, White introduced him with warmth and praise, and instructed the attendees not to “bombard him” and to give him a chance to answer their questions.

Van Bramer has in the past expressed concerns about the rezoning and the potential for redevelopment at Sunnyside Yards, though has offered some more positive words for the BQX. During the summer, Van Bramer was sharply critiqued by the Queens Anti-Gentrification Project for the many donations he has received from developers. A City Limits study—which was in circulation at Monday’s meeting—found a significant percent of his donations matched to real-estate industry search terms. But Van Bramer has also not been shy about opposing the mayor: He stopped one of the city’s first mandatory inclusionary housing developments, a 100 percent below-market building proposed by the nonprofit developer Phipps, which withdrew their application due to his dissent.

Grace Jean and Jay Koo, members of the Queens Anti-Gentrification Project, remained skeptical after Monday night’s meeting, noting that Sunset Park councilmember Carlos Menchaca has already expressed disapproval of the BQX streetcar. They want Van Bramer to take firm stances now, rather than entertain negotiations with the mayor during the public review process that results in the approval or disproval of a land use change.

It’s worth mentioning that Menchaca faced a tough primary against Assemblymember Felix Ortiz and former councilwoman Sara Gonzalez. While Van Bramer didn’t face any Democratic opponents in the primary, the Republican and Conservative party candidate Marvin Jeffcoat is now vying for his seat.

Justice for All to create community plan

Over the next few months, Justice for All Coalition’s strategy will be to continue educating the broader community about the various development projects and, with the help of the Pratt Center and LaGuardia Community College, to create a detailed “community action plan” to hand to Van Bramer.

The group already produced a 5-point-plan documenting five major demands related to these development projects. They included no rezoning unless the city agrees to employ a value-capturing mechanism to redirect some profit to NYCHA repairs; ensuring public land is developed by non-profit developers (including community land trusts) with 100 percent affordable housing; real community involvement and a consideration of how the developments will affect the larger area and their cumulative impact; the preservation of and creation of new green spaces and the passage of the Small Business Jobs Survival Act, which would require commercial landlords to submit to arbitration on rent increases. The group still intends to create a more fleshed out plan with greater stakeholder input.

Attendees at the meeting raised a variety of issues that could be addressed in that plan, including the impact of development on schools, the definition of affordability, access to jobs, and security infrastructure for public housing. One coalition member, Sunnyside Chamber of Commerce director and local activist Pat Dorfman, wasn’t willing to rule out just saying no to a rezoning completely.

“All of us could say no to all rezoning,” she posed. “It’s a democracy still.”

One thought on “Van Bramer Says He’ll Listen to Public Housing Residents on Rezonings”

I taught kids for over 30 years.when I worked the people were needy. Since the rich are taking over-be good to the people in the projects. WhT will happen to prices in local stores. This is very sensitive matter. The old residence of LIC will now see how the wealthy live. They need opportunities to get something out of this. How about vocational schools and mentors for college kids. Do these people no harm-.