Olga Caprotti, DOF

From the vantage point of the Bible Belt, New York City might look like a temple of secularism. That’s not actually the case. Not only are there thousands of churches, temples, mosques, synagogues, shrines and other spiritual sites across the five boroughs, but the municipal government loses hundreds of millions of dollars in property taxes every year that religious entities would otherwise have to pay.

This year, however, the city is getting a little Old Testament in how it administers those tax breaks, according to advocates.

Close to 400 not-for-profits—most of them houses of worship—were on the Department of Finance’s most recent list of properties with tax or water-fee debts the city plans to sell to private entities that can tack on huge fees when it collects on the lien.

According to the Urban Justice Center, more than 280 not-for-profits are on Finance’s 30-day list for the upcoming lien sale for alleged property tax debts. Another 90 or so are on the lien list for water charges the city says they owe. Several dozen not-for-profits that were on the previous version of the list have been removed, but advocates say many of those still in the crosshairs are in the process of trying to resolve the problem—an effort that is a costly burden for small not-for-profit organizations.

New York City lost $626.9 million in property tax revenue in 2011-2012 because of the exemption given to some 9,500 churches, synagogues, and mosques—40 percent of them in Brooklyn—according to the Independent Budget Office.

State law has long required the not-for-profits receiving the tax break to maintain ownership of the properties covered by the exemption and to continue to do public-service work at them.

In 2012, however, the city began requiring not-for-profits to apply annually for the exemption certifying that each property still qualified.

“We remove a non-profit owned property from the tax lien sale at-risk pool when the owner completes a not-for-profit exemption application or finalizes an incomplete application for the current year,” says Sonia Alleyne, a spokeswoman for the finance department.

Some not-for-profits, however, say that requirement ends up being more onerous than it sounds.

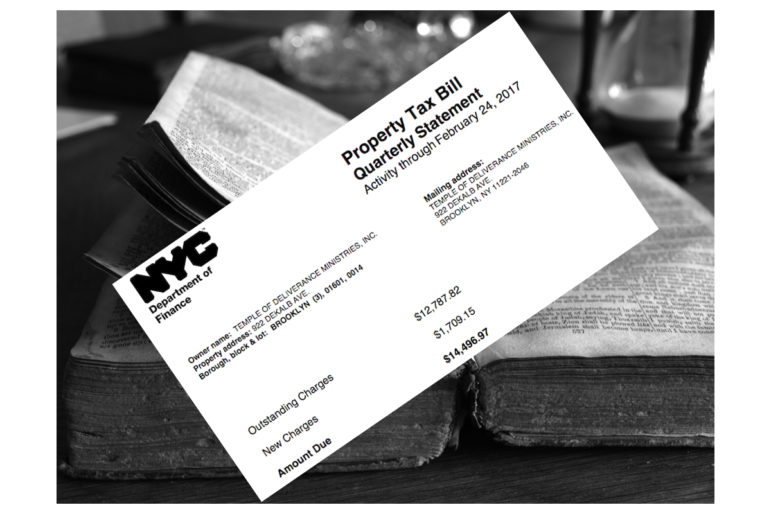

The Rev. Carmen Kelly at the Temple of Deliverance in Bed-Stuy says her building has been a non-denominational church since 1974. She insists she filed her forms for renewal of the tax exemption in 2015 but the department did not receive them.

As she sought to solve that problem, she learned that the property’s certificate of occupancy did not list it as a place of public assembly. Instead, the property is still under a 1924 certificate that indicates it is a store—even though the Department of Buildings designates it as a “church” in the building information system.

Correcting the certificate of occupancy could cost $8,000 to $12,000, Kelly says—more than a church with 30 or so congregants can afford. But not coughing up that money means the property-tax bill keeps climbing. “We’ve been going back and forth,” Kelly says. “Meanwhile the price kept going up.” The last notice listed on the finance website indicates the church owes $12,788 in back taxes.

Kelly says at least one other church in the area has faced similar problems. She sees the tax trouble as part of the larger changes sweeping the neighborhood. Her temple might have to accept change, she says, but wishes it could be done differently. “Come to the churches. Speak to the churches,” she asks. “Don’t do it this way.”