DOE NYC

Randi Levine, a policy coordinator at the nonprofit Advocates for Children, often counsels the parents of New York City public school students with disabilities who are trying to get the services their child requires from the Department of Education. She recalls a student whose parents fought to keep her school-year services going throughout the summer, demonstrating that she risked a considerable learning loss over the break without the assistance.

“We showed the skills that she loses overnight, over weekends, over school holidays, the amount of repetition that she needs, and how quickly she forgets or loses those skills,” Levine says.

The “summer slide” impacts students in different ways. Science and math losses are widespread, and slips in literacy affect students to varying degrees. But students with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to regression; without consistent services, disabled students often face the prospect of more severe losses in the summer than their peers. According to advocates for the parents of these public school students, securing services from the DOE can be a struggle during the summer months.

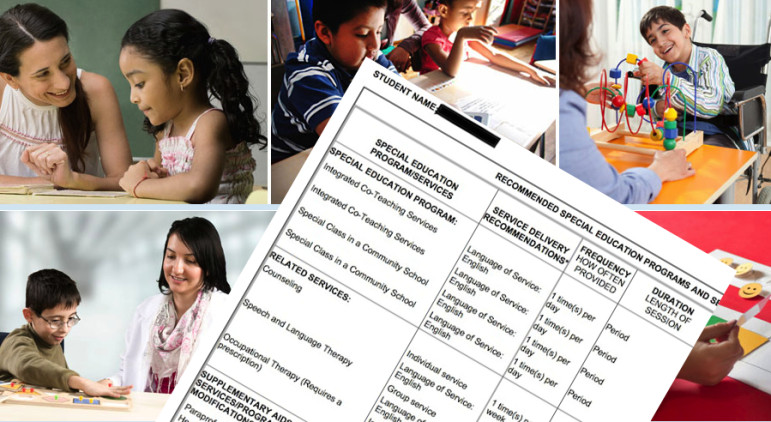

The legal framework for disabled students’ rights is four decades old. Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act stipulates that school districts are required to provide a “free and appropriate public education” to all students with disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, signed into law by President George H.W. Bush in 1990, requires that every student with a disability have an Individual Education Plan (IEP).

An IEP lays out the specific needs of the student, measurable goals, the services that are crucial to accomplishing those goals, and whether the services should last for 12 months or only through the 10-month school year. The student’s school district is required to supply these services. If the district cannot do so, and the parents find other approved service providers, the district must pay for those services.

According to state statistics, 178,933 school-age students with disabilities enrolled in New York City public schools in the 2013-2014 year, 13.9 percent of the total student enrollment. Statewide, 16.6 percent of students have IEPs, one of the five highest rates in the nation.

Who is at risk of regression?

While the majority of public-school students with IEPs have 10-month plans, some students qualify for a full year of services. According to state regulations, a student qualifies for summer services if that student is considered to be at risk for “substantial regression” if their services are not continued during the break.

The regulations don’t detail how to determine if a child is in danger of substantial regression, leaving it to each student’s Committee on Special Education—the group that writes a student’s IEP and can consist of a general education teacher, a psychologist, a school administrator, a special education teacher and the student’s parents—to decide whether such a risk exists. This lets a student’s committee judge that student’s progress on its own terms, but the process can leave educators and parents uncertain.

“It’s very individualized, where you’re looking at a student over the course of time,” Maggie Moroff, Advocates for Children’s special education policy coordinator, says.

According to Kim Sweet, the organization’s executive director, students who would benefit from 12-month services may not always get what they require.

“The danger of regression is amplified for many students with disabilities, and if there’s a likelihood of substantial regression, they need to prove it,” Sweet says. “If they go two months without the services, they might regress, but it can be very hard to get that special ed support over the summer.”

Sweet said that sometimes the school system is unable to provide the services dictated by a student’s IEP, recalling a situation where a student’s 12-month plan was changed to 10 months because the student’s school district determined it couldn’t provide help over the summer break.

Most—but not all—students with 12-month plans are enrolled in District 75, a collection of schools and service facilities throughout New York City that offer specialized support for students with more severe disabilities.

Liz Pardo, an attorney at Sinergia’s Metropolitan Parent Center who often works with parents of students with disabilities, said that parents are sometimes told during IEP meetings that students in neighborhood schools are not eligible for a full year of services because the student is not enrolled in a District 75 school—despite the student’s legal right to that help.

“They’re psychologists and special education teachers. They’re not attorneys or advocates,” she says. “What they know of students’ rights is what they’ve been practicing.”

Classroom setting must fit

Federal law requires that students with disabilities must be educated in the “least restrictive environment” (LRE) possible, and if a student with a disability can learn in a general education setting, the school district must provide whatever is necessary to ensure that happens. In 2013, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals found that the LRE mandate applied to 12-month IEPs, and not only during the regular school year.

In the past, the DOE would often send students from neighborhood schools with 12-month service plans to District 75 schools during the summer, claiming that the services students required were not available in the local schools. But that meant students who could learn in a general-education environment were often being taught in spaces and classes designed for students with more severe disabilities.

In response to the Second Circuit’s decision, earlier this year the DOE announced that students enrolled in neighborhood schools should not be sent to District 75 schools during the summer.

“This was an important development that will help ensure students are getting the services and support they need in the best environment possible,” Harry Hartfield, the DOE’s deputy press secretary, says.

Levine said that Advocates for Children had seen a drop in neighborhood school students going to District 75 schools for the summer, suggesting the DOE’s policy shift was bearing fruit. But she noted that families of students with disabilities enrolled in neighborhood schools were still being told that 12-month services were not available to those students.

“They’re told ‘because you’re in a neighborhood school, you can’t have summer services,'” she says. “Perhaps as schools become familiar with neighborhood schools with summer services, they’ll have more understanding that it’s a possibility for students who need them.”

Resources are the obstacle

Other policy changes could also help. In 2011, the DOE unveiled the Special Education Student Information System (SESIS), an online database with a profile for each special education student. On the SESIS, an educator can find a student’s IEP, evaluations and the classes and services the student has received. Though plagued with glitches and criticism, Levine says that such a system was sorely needed.

“We used to have situations where (a student’s) file would just go missing, and the student wouldn’t get a 12-month IEP,” she says. “The database has a lot of potential, and the DOE is hoping to expand on that potential.”

Moroff said that the lack of resources at the neighborhood school level was always going to be an obstacle for substantive, system-wide care for all students with disabilities.

“I do think the DOE has a ways to go; they’re working very hard to offer services for students with disabilities,” she says. “It’s a great goal, but the devil is in the details.”

This is the final story in City Limits’ summer-long series on the “summer slide”—the fear that students, particularly in low-income households, will lose ground during the summer break and the myriad efforts underway to prevent that. Read the rest of the series here.

* * * *