Spencer T. Tucker

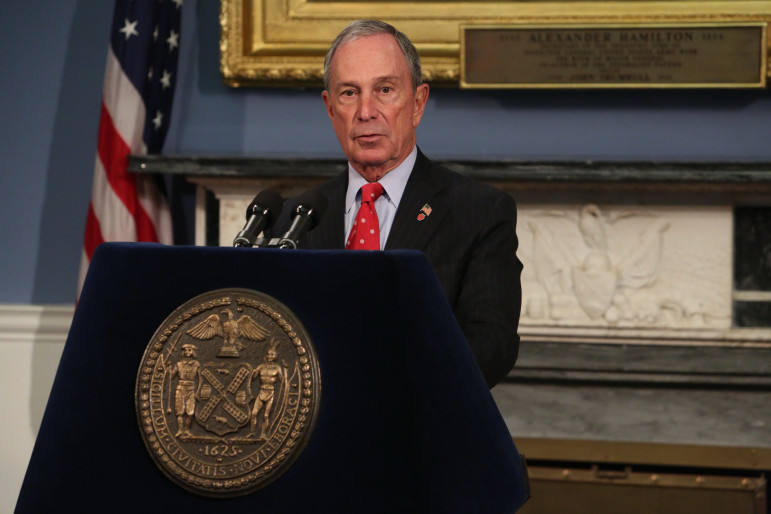

The author suggests: The author suggests we 'ask Michael Bloomberg whether the $1 billion New York City spent on rapid rehousing wasn’t wasted.'

As Ronald Reagan used to say, “There they go again.” There’s been a flurry of headlines from New York to Salt Lake City and rallying cries for the so-called shockingly simple strategy to eliminate family homelessness. Supporters claim that nationally homelessness is down and even completely eradicated in some states, all due to rapid rehousing policies. Is it in fact this simple? Is “housing first” the silver bullet we have been seeking for over 30 years?

Not so fast.

Let’s take a look at the facts. Simply arriving at the actual number of homeless people and families could be considered more art than science, as current methods for measuring homelessness are imprecise and incomplete. Consider the methodology used to support the claim that homelessness is declining. Each January, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) oversees a one-evening survey of homeless people found on the street. This isn’t a very scientific approach. To have a reliable measure, or what statisticians refer to as a normal distribution of the data, one would have to, at a minimum, perform the same street count survey each evening for at least 30 days, and even that would be open to question due to all the intervening variables that come into play, for example, weather conditions, survey locations, number of surveyors, and so on.

Another way HUD collects information is through the Housing Inventory Count (HIC), which counts available beds in the shelter system. A low number of beds counted leads to cheery reports of reduced demand and fewer homeless families. However, the number of available beds is directly linked to funding—funding that has been shifted away from shelters in favor of rapid rehousing. There is less money available, which means fewer beds—but by no means fewer families.

In other words, homelessness isn’t necessarily getting better; it is just being poorly measured.

Proponents of “housing first” claim that when families are rehoused, they do not return to the shelter system. When homeless families move to housing first, they receive subsidies funded through either the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program (HPRP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). HPRP provides short-term assistance to people who were in danger of becoming or were already homeless, ranging from rental subsidies to eviction prevention and legal services. In practice, funding streams shifted focus towards the former, rather than investing in more systemic fixes. Supporters claimed success by highlighting pilot programs that targeted families who were the best fit for this type of support—those experiencing a temporary crisis and most likely to achieve stability.

The key measure of success here is time—the families’ length of stay in a stable housing situation. When the rental subsidy ends, families should be working and able to live independently. But is that in fact the case? After 24 months, 17% of rehoused families have returned to shelter in Dayton, Ohio, and after 12 months almost 14% have returned in Philadelphia, and 12% in Michigan—and this is just factoring in those who have been accounted for. In Mercer County, New Jersey, approximately one-third of the families enrolled in a rapid rehousing program between 2009 and 2012 did not complete the program, begging the question: what happens to families who fall off the radar?

New York City is the Capitol of Homelessness. The legal right to shelter and the staggering numbers the city confronts on a daily basis effectively makes it the command center for reliable test cases, and allows for unflinching testimony on what works and what doesn’t. Between 2006 and 2012, the Bloomberg Administration moved some 33,000 families out of shelter through rapid rehousing. When the subsidies ended, the families started to become homeless again—four years after the program terminated, over 56% of rehoused families have returned to shelter. As remaining subsidies continue to trail off, the number continues to grow.

Today, deviating from “housing first” strategies results in funding cuts. This instills fear and stifles creativity among those with the most experience: the direct-service providers on the front lines of homelessness. They have been shut down by a vocal, ideologically driven coalition that advocates housing first at any cost and steamrolls over anyone who questions their methods.

For over 30 years homeless policies have been driven by one shortsighted housing initiative after another, ignoring the fact that family homelessness has never been only about the need for housing. The real issue is providing stable housing to homeless families whose homelessness stems from a number of reasons other than the availability of housing, including domestic violence and incomplete educations. These problems need to be addressed before stability can be achieved, and no “housing first” policy will achieve that.

Should the city serve as the weathervane for the success or failure of rapid rehousing? Let’s ask Michael Bloomberg whether the $1 billion New York City spent on rapid rehousing wasn’t wasted. Let’s ask the thousands of families who now find themselves entering shelter yet again, years later. Rapid rehousing was a resounding failure and holds enormous consequences for government, taxpayers, and homeless families.

The success or failure of “housing first” rapid rehousing policies in other cities and towns across the country will only come to light over time. But at least for now we should be asking ourselves, “Does housing first put families second?” Think about it.

Ralph Da Costa Nunez has served as President of the Institute For Children, Poverty & Homelessness since the organization’s founding in 1990 and also is President and CEO of Homes for the Homeless, a leading social services agency.

3 thoughts on “Op-ed: Rapid Rehousing No Silver Bullet Against Family Homelessness”

ralph if we had a competent president with some guts…..

WE NEED A WAR ON EBONICS! There is really only one way to end

all this…its behavior and functional illiteracy that is the

overwhelming problem..not race or politics.

There was no white flight in schools, parents saw the next generation of kids on a jail track and not a college one, so they moved and guess what? so did blacks. If you apply for public assistance you must sit in class 15-20 hours a week and learn English and Math for your EBT card….your FB page must be in your own name…there was no Trayvon Martin FB page but there was a gangsta one, and you must respond in English not ghetto

Let the prisoners decide how long they want to stay in jail…..cool idea…its up to you…..all you need to do is read and discuss the New York Times in front of a parole board and ask for a second chance…that could take 5 or 50 years their choice……the problem is NOT racial

discrimination, but severe functional illiteracy and we need to break the chains.

Housing FIRST is not Housing ONLY! If all they need is housing great! If they need other supports, provide them after they get someplace stable so that they can succeed. Nunez is uninformed.

Pingback: Rapid-Rehousing: Why isn’t it working? | Boston Rescue Mission