USIA

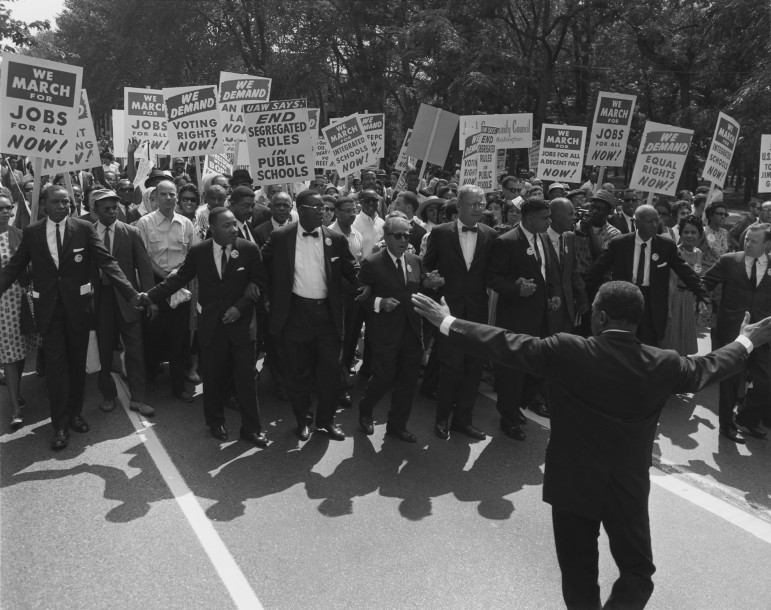

The March on Washington, 1963.

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day 2015 comes after a year when frank talk about race was unusually abundant in America, from Ta-Nehisi Coates’ case for reparations to police killings in Ferguson and Staten Island and the protests that followed. Amid those big stories were smaller ones, like the organizing effort that led to expanded sick leave benefits in New York City. Black organizers played a critical role in those stories, as they have since the days when MLK was just becoming a household name. New York Foundation is collecting black organizers’ insights in an online series called Balm in Gilead, and they shared this one from Faith in New York interim director Onleilove Alston.

I first became involved in organizing work as a member of Pennsylvania State University’s Black Caucus, when African-American students at the university began to receive hate mail. We collected data concerning racism at Penn State and used the university’s mission and constitution to hold it accountable for educating all students of the commonwealth regardless of race. We hosted rallies, a takeover of the student union building, and Black Caucus leaders negotiated with the administration around the needs of minority students. As a result of our organizing, Penn State created more minority scholarships and expanded support programs for minority students. Our work united a broad coalition of students: East Asian, White, Latino, Queer and Christian. This was my first experience with organizing and the role faith communities can play – most of the Black Caucus leaders were people of faith and we prayed hourly during the student union building takeover, and a large Evangelical student fellowship prayed for us hourly as we negotiated around the clock with the administration.

I developed my organizing skills as a student at Union Theological Seminary where I worked as a Poverty Scholar with The Poverty Initiative, a movement of over 200 grassroots organizations united in building a movement to end poverty led by the poor. As a Poverty Scholar I was mentored by Willie Baptist, a master organizer with over 40-years of organizing experience. I learned the power of sharing my story as a poor person and the importance of studying social movements such as the Welfare Rights Movement and the Poor People’s Campaign. I also developed the organizing ethic that those most affected by the issues have to be at the forefront of solving them.

I also developed my organizing skills as a founding member of New York Faith & Justice, a movement whose mission is to unite the church, follow Christ, and put an end to poverty. We worked on various economic justice issues, as well as immigration reform and environmental justice. We eventually became ecumenical and interfaith and I learned a great deal about organizing clergy and laypeople and how to articulate the Biblical call to justice.

I first learned about Faith in New York while serving as the Faith Based Organizing Associate at the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies (FPWA) where I worked with Rev. Joel Gibson to develop the Jeremiah Leadership Council (JLC). I also managed the Casey Family Programs Faith Based Partnerships Program, where we connected churches to foster care agencies through seminarian interns. One of our seminarian interns was Valerie Close of Christ Church International, one of the anchor congregations of Faith in New York. After Hurricane Sandy hit, Valerie started to organize churches in Far Rockaway despite having lost everything. At FPWA, we wanted to support Valerie so we worked with her on this effort. During her organizing work she connected with Joseph McKellar and other PICO organizers who served over 1,000 sandy affected families. Valerie told me about Joseph and Queens Congregations United for Action (which was the precursor to Faith in New York).

Currently I am the Interim Executive Director for Faith in New York so I am overseeing all of our campaigns along with our Lead Organizer Andrew Hausermann. Some of our campaigns are: Equitable Hurricane Sandy Rebuild, where we are working with the Alliance for A Just Rebuilding to ensure that the Sandy rebuild leads to affordable housing and local careers and not gentrification and displacement, and the Campaign for Citizenship (C4C), a PICO National campaign for comprehensive immigration reform.

In New York City, a main priority of this campaign was the passage of Municipal IDs for all New Yorkers, and after a successful campaign this summer we are now working closely with the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA) to ensure that the Municipal ID is not a scarlet letter for undocumented people. We are in the Real Affordability for All Coalition and over the next year we will be working a great deal on affordable housing.

Finally, we are working with PICO National on the Live Free NYC campaign which is the local branch of the Live Free national campaign to end mass incarceration and gun violence through state and federal policy changes. In New York City, one of our Live Free priorities is the passage of the Fair Chance Act which would “Ban the Box” on job applications. All of our campaigns have a common thread of racial justice running through them and our overarching campaign theme is Building the Beloved City: Creating a City with Economic Dignity for All. It should be noted that all of our campaigns are shaped by the needs of our members.

I think faith is such an important part to African-American organizing because we are a spiritual people, and when you look at the Biblical narrative we see multiple examples of organizing: Moses being taught to organize the newly freed Hebrew masses after the Exodus by his African father-in-law Jethro, Jesus organizing his 12 Disciples to preach the gospel, and the Apostle Paul organizing the early church across the Roman Empire.

Black-led community organizing at its best is motivated by the spiritual principal that everybody is somebody in God and because of this we all deserve to be treated with dignity. Due to necessity, African-American clergy had to be organizers as well as ministers, and so in our faith communities there has been an unspoken expectation that our religious leaders would also be community leaders, though sadly this is changing as we integrate more into the dominant religious culture.

I think the most important factors in successful black organizing are:

1. Cultural Competency: understanding our culture whether that be African-American, Caribbean, or African, and organizing in a way that respects our cultural values.

2. Cultivating indigenous leadership that comes from the community and has experienced the issues first hand. By cultivating indigenous leaders you empower your base by knowing that they do not need to look to others to lead them but that they have what they need for liberation in their community.

3. Respecting the spirituality of historic Black organizing. Though not all African-Americans are spiritual, a great many are, and many also first learned of organizing through the work of Rev. Martin Luther King and the African-American Church. To ignore this legacy is unwise when it provides a culturally competent framework for organizing.

During my years of organizing I have seen a pattern where organizers have been people who were not from the cultures or communities being organized. When we look at the leadership in the field of community organizing, many are not people of color, which has contributed to a decline in Black-led organizing work. Most often when we think of Black-led organizing work we think of the Civil Rights Movement, which was over 50 years ago, and though great Black-led organizing is still occurring it is not given the same honor, respect, and funding as organizing led by the dominant culture.

I think mining for gold in communities of color and finding indigenous leaders and providing a pathway for them to take leadership in a way where they can bring their authentic selves to the field of organizing. Furthermore, it is important to fund Black-led organizing. Recently there have been studies revealing the lack of funding given to African-American led organizations, and if we truly value African-American organizing we will have to support it through funding and leadership development opportunities. Black-led organizing may look different from the traditional Saul Alinsky model, but it has vastly changed the landscape of our country and influenced modern social movements around the world.