Grace Saffran Ashford

A mural honoring the NYPD in the 106th precinct.

Sean Ali is 32 and works for the Department of Sanitation as a diesel mechanic. In his spare time, he works on upgrading and modifying his car—a Honda Civic SI with a lowered suspension and exhaust system. But he doesn’t drive it around anymore.

“Every time I drive that car in this neighborhood I get pulled over,” he says. The most common explanation Ali has gotten from police for the stops is that cars like his “get stolen a lot.” It got so bad that last year he caved and bought another car, an unassuming 2015 Jeep Cherokee, so that he could drive to and from work in peace. In his Jeep, he hasn’t had any problems.

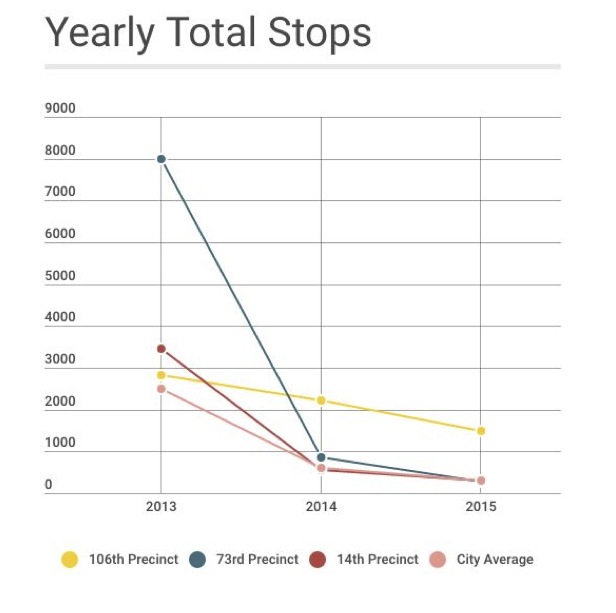

In 2014, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio rode into City Hall with a promise to end the aggressive “overuse” of stop-and-frisk tactics. The numbers suggest that he has been largely successful: From 2013 to 2015 total stops fell by 88 percent citywide. In Brooklyn’s 73rd Precinct, stops are down 96 percent, from over 8,000 to 285.

But in the nearby 106th Precinct, a sleepy residential community in South Central Queens, they are down by less than half. Here guys like Ali are still being stopped with some frequency—more than 1,400 times in 2015—on their way to work, and the mosque and the grocery store. It’s stops like this that are quickly making the 106th Precinct one of the most stopped-and-frisked places in New York City.

A boost in murders

Encompassing the residential neighborhoods of Ozone Park, South Ozone Park, South Richmond Hill, Howard Beach, and Lindenwood, the 106th Precinct is a quiet area full of single family homes and posters that say things like “lost cat” and “found car keys.” You can see vestiges of the old neighborhood—pizza parlors collecting dust and bakeries that now sell cannolis alongside West Indian treats—but most of it is gone, replaced by shops selling brightly colored saris and head wraps dotted with sequins. In the late 1980s, the area saw an influx of immigrants from Guyana and Trinidad, seeking affordable homes and easy commutes to midtown Manhattan. This year, NYU’s Furman Center ranked it No.1 on its Diversity Index.

Gavin Singh, 37, remembers being the first Guyanese family on his block when he moved with his parents in 1988. Now, they own their own business, a police uniform store and manufacturing outfit in Ozone Park. He described it as an “area of prosperous immigrants,” where handwork and ownership are tantamount.

This is why the recent murders—seven this year, including the high-profile shooting death of a local Imam and his assistant, and the killing of a jogger in Howard Beach—hit the community so hard.

It’s why some residents—Ali included—support stop and frisk. “I believe it works and I believe it should be reinstated,” he says. “With everything that’s been going on lately, I think we definitely do need it. But the problem is, I believe the police are going after the wrong people.”

In the past year Ali estimates that he has been stopped seven or eight times. None of these stops resulted in arrests, he says. According to statistics released by the NYPD, fewer than 9 percent of stops in the 106th Precinct resulted in arrests in the year 2015.

Where stop-and-frisk survives

Grace Saffran Ashford

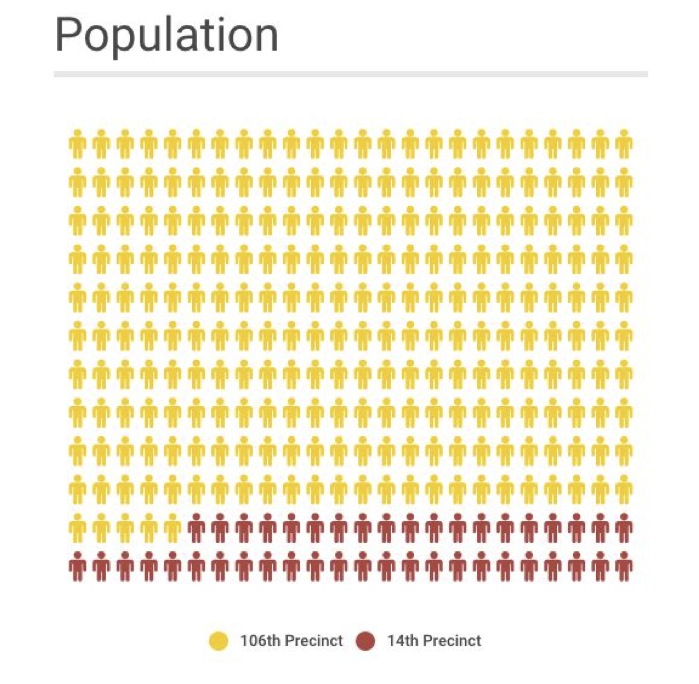

There are many different ways to look at statistics. Each view tells a different story. You can look at total stops-per-precinct, as is shown in the table above. This view shows how, in 2015, the 106th Precinct had more than twice as many total stops as any other precinct in the city (1481), and more than three times as many as Manhattan’s 14th Precinct (311).

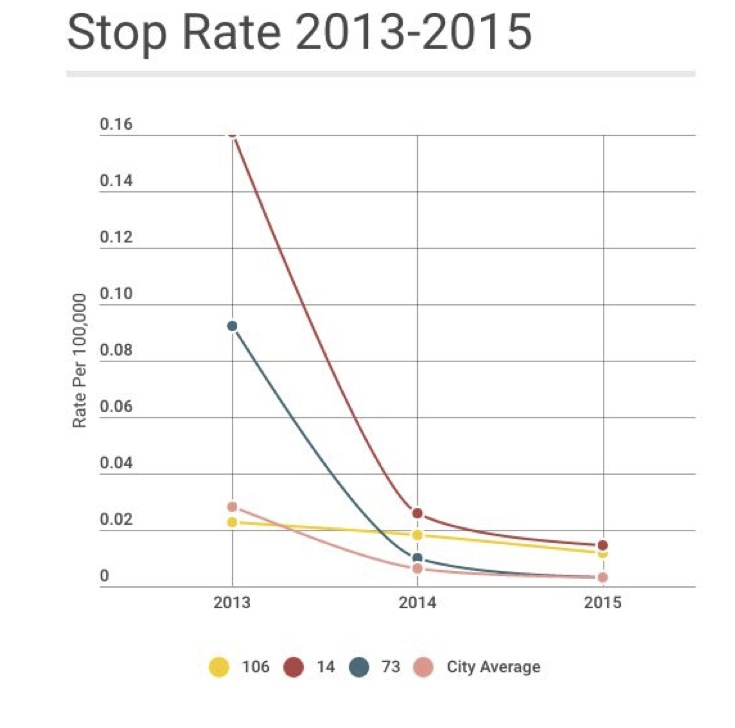

But total stops are just numbers in a vacuum—they cannot be used for comparison. For that type of analysis, one needs to distribute total stops over the population of the area. In the second table, it’s clear that the 14th Precinct has the highest stop rate (though all are declining). This is because the 14th Precinct, which encompasses Penn Station, Madison Square Garden, Port Authority, Grand Central, and the bottom half of Times Square, has only 21,449 residents, according to the 2010 census. But, as anyone who has walked down 42nd Street can tell you, it is also a bustling commercial nexus that millions of people pass through each day, none of whom figure into the stop rate because they do not technically reside in the 14. *

Grace Saffran Ashford

The 106th Precinct has a much larger population — 123,402. As a remote, residential area, it does not get many tourists or business commuters passing through. When you divide the 106’s total stops by the population you get a rate that is slightly lower than in the 14’s. So is the 14th Precinct the most stopped place in New York City?

Not exactly. Because with precincts as different as the 14 and the 106, stop rate isn’t a perfect way of looking at the numbers either. Without a count of total population passing through each precinct each year, the only thing one can do is look at the numbers and see what makes sense.

It makes sense that Manhattan’s 14th Precinct would have a high stop rate—it encompasses the heart of metropolitan New York City, a center for petty theft and a target for terrorism. It also has a small residential population and a high volume of passersby who artificially inflate the stop rate. Some 300,000 people walk through Times Square alone each day, according to the Times Square Alliance. That’s 300,000 people, 365 days a year.

What doesn’t immediately make sense is why the residential 106th Precinct, with its mosques and churches, large resident population and comparably low overall crime rate, would have a Stop and Frisk rate that is nearly the same.

Grace Saffran Ashford

An evolving policy

In 2013, Federal District Judge Shira Scheindlin wrote a blistering 198-page decision which found that NYPD had been stopping people without reasonable suspicion, and that those people were disproportionately black and Latino, in clear violation of the fourteenth amendment. The city initially appealed this decision and the case was remanded back down to the district court to be reheard by a different judge. When de Blasio took office in January 2014, he dropped the appeal, enrolling the city in the remedial process as ordered by the district court. One of the requirements of that process are a series of public forums designed to get community members opinions and suggestions for improvement in community policing. The first forum took place in November in South Richmond Hill. Organizers were stunned at the turnout of over 50.

“To be honest, we weren’t really expecting such a high number, but people really came out for it,” says William Depoo, a Queens-based activist with DRUM (Desis Rising Up and Moving), the working-class, South Asian diaspora activist group that put on the forum in partnership with Communities United for Police Reform (CPR). He says that the forum and outreach touched a nerve within the Indo-Caribbean community in particular, where discussions of policing and discrimination are rare. Depoo says the forum, like the neighborhood, was split, with some for and some against stop-and-frisk. “We did run into both [sentiments] doing outreach and engagement,” he says, “however, we did find …a lot more feel like it was discriminatory.” He went on to add that, “The data shows there is racial profiling. We can’t ignore that.”

In 2015, whites made up only 16 percent of stops in the 106th Precinct, although, according to the 2010 census, they account for 35 percent of the population. When pressed, Ali admits that he does think he’s been ethnically profiled. “They’re obviously looking at me like I’m a criminal because in their eyes I probably look like a criminal,” he says, adding “Its not like a Guyanese cop ever pulled me over.”

Yet Betty Braton, Chairwoman for Queens Community Board 10, says that stop and frisk is “not an issue that comes up,” in the precinct, adding “If people are being stopped they [police] are doing it properly.” Chairwoman since 1990, she quipped, “over the years I’ve found that if people are irked about something they complain.”

Depoo suggests that cultural norms might keep his community silent: “[In the] Indo-Carribean community, policing is not something we talk about because we associate when someone gets stopped by the police or even arrested as them ‘being a criminal’,” he says. “There’s also this aspect of you just internalizing being stopped by the police, and not being able to talk about it because there aren’t spaces …to talk about it.” He went on to explain the bargain many first generation immigrants feel they must make, trading a lack of economic certainty at home for lack of social power in the United States. “When they come here, they feel like, ‘OK, if a police officer stops me, or if I get discriminated [against] in some way at work or something, it’s a compromise.'”

Andrew Mackhanlall, a local real-estate broker, agrees that the mindset of many of his neighbors, first generation Guyanese, Trinidadians and Punjabis, could make them compliant in the face of authority. “These people are immigrants,” he says. “When a police stop them they are afraid. They don’t know their rights.”

Ali does, however. He has reported instances of stops he considers unlawful to the Civilian Complaint Review Board and Internal Affairs, he says, adding, “I’ve never really been mistreated by any other precinct anywhere in the world my whole life, except for this one.”

‘We live in peace’

The continued use of stop-and-frisk does not seem to have had the desired effect on crime in the 106th: There were seven murders in 2016, up from 3 in 2015 and 1 in 2014. Stops are up too: First and second quarter data show that between January and June of 2016 there were 789 stops, putting the precinct on track in 2016 to exceed the previous year’s total. In the first half of 2016, there were almost twice as many stops in the 106th as there were in the precinct with the second-highest number of stops, the 49th precinct in the Bronx, which posted 399. During the first six months of ’16, there more stops in the 106th than in the 29 precincts with the fewest stops combined.

“This is mostly a Muslim community … We live in peace,” says Tanzid Hossain, a representative of Al-Furqan Jame Masjid Mosque, where Imam Maulama Akonjee, 55, and his assistant, Thara Uddin, 64, worked before they were killed on August 13 in the highest profile of the precinct’s 2016 murders. He admitted that the mosque had “had incidents of Islamophobia [before] however, nowhere near the degree of the murder of our beloved Imam.” Oscar Morel, 36 of Brooklyn was indicted in August of first and second degree murder for the killings but has not been charged with a hate crime. In September, he pled not guilty. Since the incident, Hossain reported, the police have been very helpful, providing additional security around the mosque.

The toll on the community is visible in shop windows and telephone poles, where information posters hang, reminding residents to keep their eyes open and pass along anything they know to police. Under the raised subway tracks which stretch over Linden Avenue like a bridge, near the center of the precinct, sits a local artist’s mural lauding strong and bold NYPD and 911 first responders.

Ali is pensive. “I feel like if they did their job better, maybe some of these people that were killed this summer didn’t have to get killed,” he says.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. In the meantime, residents of the 106th Precinct will drive their Jeep Cherokees and lock their doors at night.

* Excluded from this analysis is the 22nd Precinct – Central Park. Stop rates are exponentially higher here than elsewhere based on the low number of permanent residents (25) and the multitude of nonresidents who pass through each day. The 38 total stops from 2015 gave the 22nd a 150 percent stop rate.