About 290,000 Asian Americans in the New York City Metropolitan Area experienced poverty in 2019, up from 252,000 in 2010, researchers from the Asian American Federation (AAF) found.

Asian American Federation (AAF)

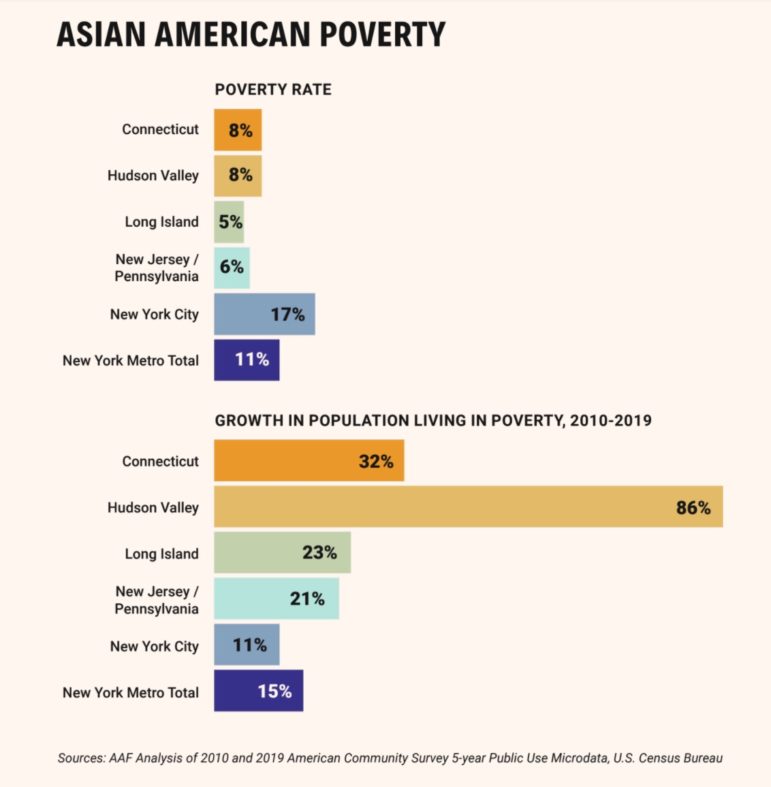

Researchers from the Asian American Federation (AAF) found that about 290,000 Asian Americans in the New York City Metropolitan Area experienced poverty in 2019, up from 252,000 in 2010.The number of low-income Asian Americans in and around New York City rose by 15 percent over the last decade, with more poorer residents moving to suburbs with limited social services, according to an analysis by a leading advocacy organization.

Researchers from the Asian American Federation (AAF) found that about 290,000 Asian Americans in the New York City Metropolitan Area experienced poverty in 2019, up from 252,000 in 2010. The spike corresponded with an overall rise in the local Asian American population—an extremely diverse collection of immigrants and US-born residents who make up the nation’s fastest-growing racial or ethnic group.

Despite the increase in the overall number of low-income Asian Americans in and around New York City, their poverty rate decreased from 12.4 percent in 2010 to 11.5 percent in 2019, the report found. However, the incidence of poverty undoubtedly increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors said. The report was based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey collected before the COVID crisis, but dedicates a section to the social and economic impact of the pandemic.

Average income levels vary by age, location and specific ethnic group, but researchers found that Asian Americans of Mongolian, Burmese, Bangladeshi, Cambodian, Chinese, Pakistani and Malaysian descent accounted for the highest rates of poverty. Seniors were also more likely to experience poverty.

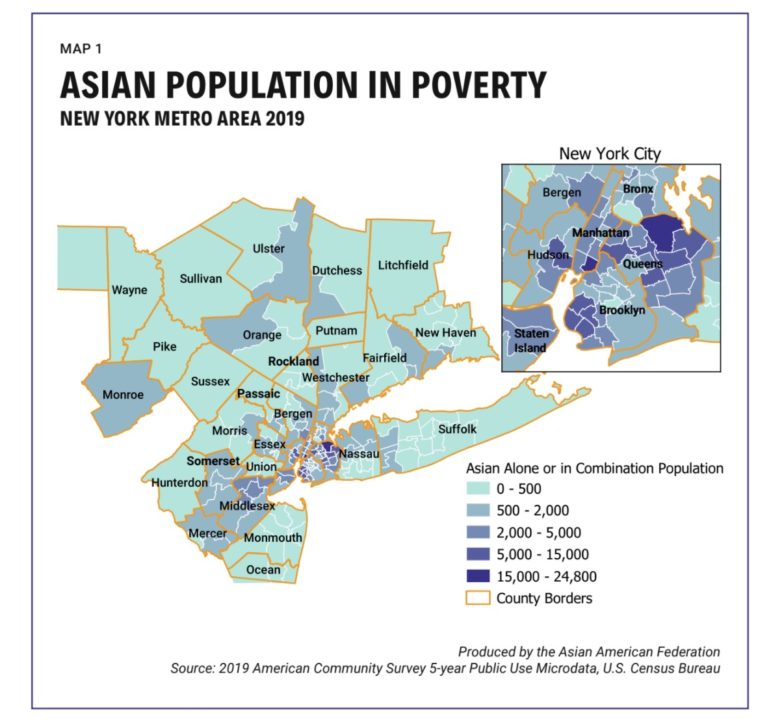

While most low-income Asian Americans remain concentrated in New York City, a growing number are moving to suburbs where housing and cost of living are less expensive, the report found.

Yet those moves come with various challenges for households at or near the poverty line, said AAF Director of Research and Policy Howard Shih. Suburban parts of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania rarely offer culturally accessible services in participants’ native languages, underscoring a key finding of the report, he said.

“They are moving for schools, or for better housing considerations as well as economic opportunity,” Shih said. “And so the consequence of that is we have to start thinking about the services.”

The researchers specifically highlighted the rise in Asian American poverty across the Hudson Valley, where the Asian American population grew by 16 percent between 2010 and 2019, fueled by a surge in the number of new residents of Bangladeshi descent. During that period, the number of Asian Americans living in poverty rose by 86 percent in Dutchess, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Ulster, Sullivan and Westchester counties.

Many of those low-income residents end up traveling from the Hudson Valley and other suburban areas back to New York City to access services or connect with their social networks, Shih said. “So we need to figure out how we create the infrastructure in the places where the people are living now,” he added.

Some AAF member organizations based in the five boroughs have already begun setting up satellite offices in New Jersey, where the Asian population has boomed, he said.

The report recommends further expanding senior services, childcare, language access, education and workforce development outside New York City. AAF has also called for easier pathways for immigrants seeking to transfer professional credits from their home countries to the U.S.

Queens Rep. Grace Meng said AAF’s findings illustrate the need for programs she has pushed for in Congress, like initiatives to increase language services and support for seniors. “In order for benefit programs to address the root problem of poverty, those with limited English proficiency must be able to navigate them in an equitable manner,” Meng said.

The researchers also analyzed the specific Asian American groups most likely to experience poverty in the Metro region. Chinese Americans, including immigrants, accounted for 48 percent of the Asian population at or near the poverty line, but poverty trends vary in different counties and states. In New Jersey and Connecticut, for example, Indian Americans accounted for the largest percentage of low-income Asians.

The authors also found that Asian American immigrants living in poverty were more likely to be non-U.S. citizens or those who have lived in the U.S. for less than 10 years. The 16 percent poverty rate among non-citizens outpaced that of Asian Americans with U.S. citizenship (9.5 percent), and female Asian immigrants in New York City had a higher poverty rate than male Asian immigrants—16.7 percent for women compared to 14.2 percent for men.

On average, low-income Asian Americans have a higher employment rate than their peers in other racial and ethnic groups. But in many cases even full-time jobs aren’t enough to lift families out of poverty, the report found. Nearly 19 percent of Asian Americans living in poverty worked in restaurants or the food service sector, about 5 percent worked at colleges, 4.2 percent worked in construction and 3.9 percent were taxi or limo drivers.

AAF Executive Director Jo-Ann Yoo said the findings should alert the region to the comprehensive needs of a fast-growing population, and the important role of media, community leaders and other institutions in affecting change.

“Providing relevant services will require outreach that makes use of cultural networks, ethnic media, and trusted voices and leaders in the community, and could go a long way to lifting this community out of poverty,” Yoo said.