Alisa Pumps It Up!

Two years ago, City Limits reportedthat families in the lowest income brackets are the most rent burdened—contrary to the common claim that it’s middle class families, unprotected by social safety nets, who are hurting. At the time, some readers questioned whether our analysis, based on census data from the American Community Survey (ACS), adequately accounted for families that receive Section 8 rental assistance. It was a fair question, since the census survey is conducted in a manner that makes it unclear whether renters are entering the rent on their lease or what they actually pay.

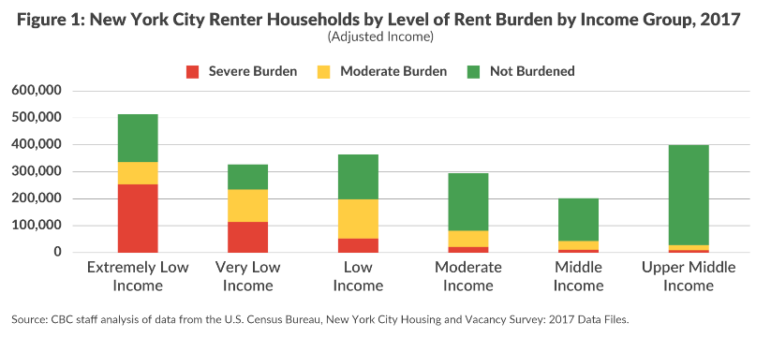

But a recent report by Sean Campion of the Citizens Budget Commission confirms that, even if you take into account Section 8 and other forms of rental assistance, the rate and number of people with “severe rent burdening”—defined as a household spending more than half its income on rent—grows significantly as one moves down the income spectrum.

The report uses data from the latest New York City Housing Vacancy Survey (HVS), which, unlike the American Community Survey, includes a survey question that explicitly takes into account whether families are assisted by Section 8, the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE), shelter allowance, and other federal, state or city housing subsidies. Citizens Budget Commission further improved the calculation by adjusting family incomes for whether or not households received food stamps.

Taking into account voucher assistance does mean that among extremely low-income households, there’s a lower rate of severe rent burden than we originally thought. But our main observation holds true: the poorer the low-income household, the higher the rate of severe rent burdening. 49 percent of “extremely low income” households (that’s equivalent to about $28,000 or less for a family of three, according to federal metrics) are severely rent burdened, as opposed to 34 percent of “very low income” households (those in the $28,000 to $47,000 bracket) and 14 percent of the “low income” households (those in the $47,000 to $75,000 bracket).

And those making above $75,000 are largely spared. Of all the city’s severely rent burdened households, only five percent are moderate income families ($75,000 to $113,000 for a family of three) and only two percent are middle income families ($113,000 to $155,000).

[/caption]

[/caption]

In the report’s diagrams, there are some complexities worth noting: The level of “moderate rent burdening”—the rate of households paying more than 30 percent, but less than 50 percent, of their income on rent—is actually higher for families in the low-income, $47,000 to $75,000 range than for extremely low-income families making less than $28,000. That means that while many low-income families are dealing with a heavy, but still manageable, rent burden, extremely low-income families fall more squarely into two buckets: either they’re receiving assistance, or they’re barely making ends meet and are perhaps on the brink of homelessness.

Another nuance: While extremely low-income families have the highest number of people facing some kind of rent burden, moderate or severe, the very low-income bracket (those making between $28,000 to $47,000 for a family of three) are the group with the highest rate of some kind of rent burden, moderate or severe.

The report also observes that there has not been a great deal of change between 2017 and 2014, when the HVS was last conducted: In the population overall, rent burdening hasn’t really gotten worse, but it’s not getting better, either. One difference is a higher rate of extremely low-income people who are rent burdened, either moderately or severely (66 percent in 2017, as opposed to 54 percent in 2014); greater analysis is required to identify the significance of those figures, Campion says.

“As of 2017, more than 462,000 households in New York City were severely rent burdened,” the report concludes. “Nearly 80 percent of these severely rent-burdened households are [Extremely Low Income or Very Low Income]–a total that exceeds the mayor’s entire 300,000 unit Housing New York plan. The city cannot be expected to handle the affordability problem on its own.”

Out of the 300,000 units in de Blasio’s affordable housing plan, the city has promised that 50,000 apartments, or 25 percent of the total, will be targeted to families in those two lowest income brackets, who make up about 46 percent of the city’s population. The city is so far significantly exceeding that goal, with 39 percent of units dedicated to those families. Still, as advocates long pointed out, the plan does not correlate with levels of need as measured by rent burdening.

The Citizens Budget Commission does not discuss how many units in the city’s plan should be dedicated to these two lowest income brackets, but it emphasizes the importance of strategies that help people raise their incomes, as well as the necessity of increasing state and federal assistance.

Housing units for the lowest income families require some form of operating subsidy, which has traditionally been funded by the federal government in the form of Section 8 or public housing.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Housing Needs

The Citizens Budget Commission report is all the more valuable because the city itself has not published any tables with rent burden broken down by income bracket. Campion argues that to have a real discussion about the effectiveness of the mayor’s housing plan, it’s important to at least understand which groups have the greatest housing needs.

This concern was also raised by advocates participating in Where We Live, the city’s assessment process to evaluate its compliance with fair housing law. According to federal definitions, the definition of “fair housing” includes ensuring that no “groups of persons, based on race, color, religion, national origin, sex, familial status, or disability, experience greater housing needs when compared to other populations in the jurisdiction and region.” While the city’s Where We Live presentations have included information on rent burdening levels broken down by race, advocates have said it’s additionally important to look at rent burden by income group.

Furthermore, in neighborhoods the city is targeting for a rezoning to promote the development of new housing, community advocates have suggested comparing which income groups in those neighborhoods are most cost-burdened with which groups new housing generated by a rezoning will serve. Some activists have argued that if an extremely low-income neighborhood is required to accept a rezoning, all new apartments should be affordable to existing residents. Others might dispute this contention—by arguing that it’s important to build housing for a range of incomes to foster economic diversity or because young professionals, teachers and fireman do need affordable housing too, even if not quite as urgently—but it’s hard to dispute the importance of at least gathering data on the rent burdens faced by different groups of existing residents in the neighborhood. Furthermore, rent burden data could be an important part of assessing how many people would be at risk of displacement if rents rise.

There are currently no published data tables on the rent burden levels broken down by income bracket at the neighborhood level, though Campion says he’s processing and analyzing the HVS microdata.

In an e-mail to City Limits, a spokesperson for HPD explained that the agency does believe it’s useful to look at rent burden per income bracket using data in HVS—and that the agency does study this data for the city as a whole. The agency says its warier to rely on data for smaller geographies due to accuracy concerns, given the dataset’s margin of error, but that the agency might look at these geographies using bigger income-bracket groupings.

In other words, HPD is well aware of the data. But it’s just not talking about it publicly that much.

“If we’re not thinking about the city’s various housing programs and tools in terms of how they address our housing needs, then we can’t properly measure their success or failure, or think strategically about how to prioritize resources and tools,” wrote Chris Walters, rezoning technical assistance coordinator at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, in an e-mail to City Limits.

Walters says he gets HPD’s reluctance to drill down too deep into the HVS data, and acknowledges the limitations in the alternative ACS statistics. But the uncertainty around the existing numbers is a reason to think more, not less, about the question of whether the city’s affordable housing programs are meeting the deepest needs. He adds: “All of these data sources consistently indicate that the brunt of the affordability crisis is borne by the lowest income New Yorkers.”

2 thoughts on “New Data Confirms Familiar Concern: Low-Income NYers Face Harshest Housing Market”

NYC always was and always will be an expensive place to build apartment buildings or any other form of housing. In my S.I. neighborhood even with the long commute new 2-family homes sell in the $800k range, which is crazy but that’s what it is. Land and labor are not cheap here. Not everyone can afford to live here.

https://www.realtor.com/realestateandhomes-search/10306/type-multi-family-home

Hi I’m interesting to apply for a housing. I think I qualify be my income is low 44,000 per year. Thanks