Seven workers’ organizations have compiled a database on wage theft during the pandemic totaling $130.5 million owed to workers. The preliminary data from just seven groups dwarfs the nearly $3 million Gov. Kathy Hochul boasted of the state having recovered for workers last year. A preliminary version of this data has been shared with City Limits.

Don Pollard / Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

Gov. Kathy Hochul announcing a “multi-pronged effort to combat wage theft” in July 2022.Leer la versión en español

Systemic problems require systemic tracking: that’s the mindset of several New York workers’ rights groups that have been collecting data on wage theft cases reported to both their organizations and the Department of Labor (DOL) since the pandemic began, which they say totals $130.5 million owed to workers across the state.

The organizations—Queen City Workers’ Center, Flushing Workers Center, Don Bosco Workers Inc., The National Mobilization Against Sweatshops, Laundry Workers Center, Chinese Staff and Workers Association, and The New Immigrant Community Empowerment—have been collecting data on both the cases they report directly to the DOL and those handled internally by the organizations seeking to recover workers’ wages.

Their data pertained specifically to workers they say are still unpaid and haven’t recovered their wages yet, and five of the seven organizations provided cases tracked from 2020 to 2022. Cumulatively, the groups counted a total 1,698 wage theft complaints, of which more than 70 percent were lodged over the past year, representing thousands of workers.

The Chinese Staff and Workers Association (CSWA) alone says it filed 850 cases of unpaid wages with the DOL on behalf of New York home health care workers in 2022. According to CSWA’s calculation, the money owed to these workers amounts to more than $100 million. The National Mobilization Against Sweatshops (NMASS), another organization that shared its data, filed more than 50 cases with the DOL in 2022, a 30 percent increase over 2021. The preliminary data from just seven groups monumentally dwarfs the nearly $3 million in recoveries Gov. Kathy Hochul boasted of the state collected for wage theft victims last year.

The seven workers’ organizations put together the database after several years of fighting for workers to recover their salaries—what can be an uphill battle, even when courts rule in their favor. The groups are part of the Securing Wages Earned Against Theft (SWEAT) Coalition, which has been pushing for stricter wage recovery policies alongside grassroots organizations, workers centers, legal service providers and advocates.

“Even when workers do file and win wage theft cases, it is difficult to collect on the judgment,” said Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal, who sponsored the Securing Wages Earned Against Theft (SWEAT) bill in Albany. “Unscrupulous employers have long followed the same script: not paying their employees’ wages, filing for bankruptcy, dissolving their business or hiding behind a series of shadowy LLCs to frustrate collection. Workers know the difficulty in collecting their stolen wages, so for many, they don’t file a claim.”

The SWEAT bill would protect workers from wage theft by giving them the ability to place a lien on their employer’s assets if they have not been paid their earned wages—even if the employer goes out of business or files for bankruptcy.

“When workers pursue unpaid or stolen wages in court,” Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal explained, “employers often exploit the months or years it takes to get a judgment and use that time to transfer money from their bank accounts, declare bankruptcy, hide property and assets in the names of family members, close down businesses only to open again under a new name, and create sham corporations to evade liability.”

Wage theft can take many forms: overtime and off-the-clock violations, failure to pay the minimum wage, illegal deductions, wrongfully misclassifying employees, among others. It disproportionately affects immigrants, people of color, women, and low-income workers.

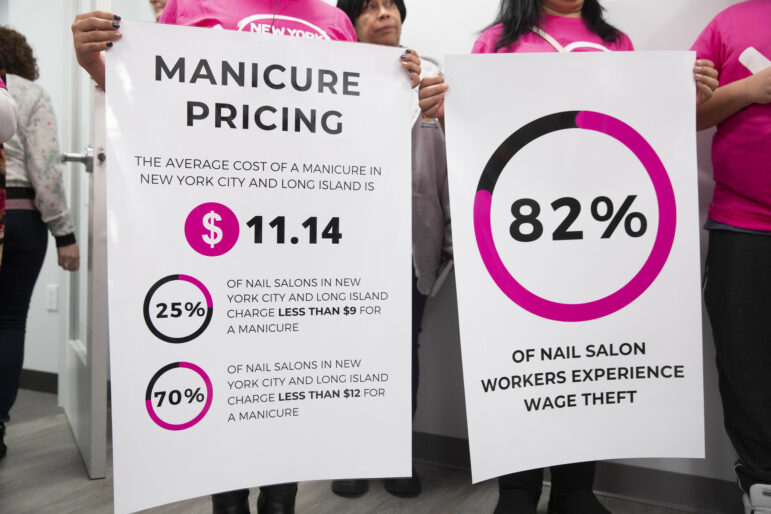

It affects “construction, hospitality and restaurant work, nail salons and domestic work—-any sector with a high concentration of low-wage or immigrant workers who may not know their rights, or may be afraid to seek recourse because of their immigration status,” explained Astrid Aune, communications director for Queens State Sen. Jessica Ramos, who sponsored the SWEAT bill in the State Senate.

John McCarten/NYC Council

Workers and city councilmembers held a rally about wage theft in the nail salon industry, February 2020.

Different versions of the bill have been introduced in the state legislature for years, have advanced out of committee and even been approved by lawmakers, but failed to become law. In 2020, for example, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo vetoed the legislation citing “due process concerns.” In 2021, the SWEAT bill passed the Assembly (where it had also passed in 2016 and 2019) but not the Senate.

The bill has recently been reintroduced in both chambers this year (A46/S1977).

“I will be working to pass it in the Assembly once again so it can make its way to Governor Hochul’s desk,” said Rosenthal, adding that periods of crisis and higher unemployment make low-wage workers more susceptible to wage theft.

“During the country’s recession in 2007-2009, these workers lost on average 20 percent of their hourly wage from minimum wage violations and it would not be surprising if the same proved to be true during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic,” the lawmaker said.

The Department of Labor (DOL) did not respond to City Limits’ questions about the number of wage theft cases it handled during the pandemic, directing inquiries to their Freedom of Information office. They said that they have recently added investigators to work on wage theft cases, though did not specify how many.

Gov. Hochul in July announced a state “crackdown” on wage theft that included the launch of a telephone hotline and online system where workers can report violations. Assemblywoman Latoya Joyner, chair of the Assembly Labor Committee, has also urged the DOL “to enhance transparency by creating a single searchable database for all of the wage theft complaints that NYSDOL and local prosecutors receive.” Such a tool does not yet exist, making it harder for lawmakers to adequately address the problem, advocates say.

Several of the workers’ groups that have been tracking cases internally have seen an increase in people reporting wage theft.

“We saw a huge increase in workers coming forward in 2022,” NMASS Organizer Jihye Song said in an email. “This doesn’t necessarily mean there was more wage theft in 2022 (workers who came forward that year reported that their wages had been stolen the previous years as well), but rather, speaks to workers’ increased willingness to fight back against this system of exploitation.”

The New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE), a workers organization that mostly serves construction, restaurant, domestic, and cleaning workers, said it managed 530 cases of wage theft in 2022 alone, totaling a little over a million dollars owed, most of it from construction workers’ petitions.

Over the last few years, NICE has noticed a steady increase as well: 357 cases in 2018; 377 cases in 2019; 410 cases in 2020; and 503 cases in 2021. “We saw an increase at the beginning of the pandemic,” said Sara Feldman, the group’s director of worker rights, though she too was cautious about making a widespread generalization. “More people heard about us during the pandemic, more people came and more spoke up.”

Three of the seven organizations in the database organize largely around home health aid workers, so the vast majority of their cases were related to this industry, which last year saw battles at the state and local level to increase wages for workers and outlaw 24-hour shifts. Those groups—CSWA, NMASS, and Flushing Workers Center—say they’ve handled complaints totaling $128 million owed to workers in 2022.

According to the seven groups, the cumulative amount of money owed to workers across all organizations that has still not been recouped grew from $12 million in 2020 to $130.5 million in 2022.

“As you can see the amount owed is increasing exponentially every year without SWEAT [bill] as a law,” said Laundry Workers Center Co-Executive Director Rosanna Rodríguez.

Since wage theft affects disproportionately low-wage workers who are living paycheck to paycheck, the money owed can mean the difference between their being able to pay bills or feed their families, advocates and legislators say.

“The process for workers to seek remedies for wage theft heavily favors employers who have more time and resources,” said Aune. “This is the precise reason we are fighting for SWEAT—workers need means to bring employers to the table to settle wage theft complaints.”