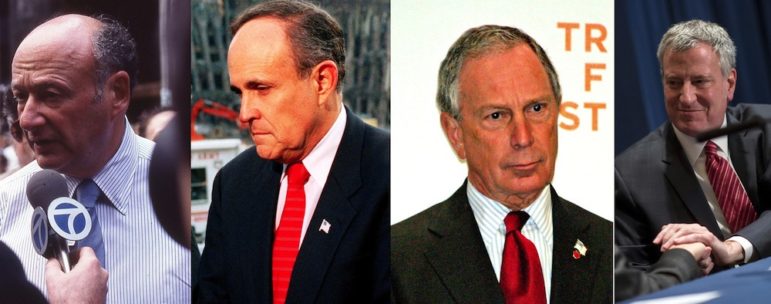

B. Golladay, DOD, D. Shankbone, E. Reed

A 1989 executive order by Mayor Koch was something Mayor Giuliani went to court to defend after 1996 federal law changes. Mayor Bloomberg issued the current executive order in 2003 restricting the collection and sharing of immigration information, and Mayor de Blasio has reiterated that those rules still apply.

Despite ramped up immigration enforcement and threatened federal funding cuts, New York City’s protections of the immigration status information of non-U.S. citizens who use city agencies—including homeless shelters—seem sturdy enough to withstand federal pressure, immigration law experts say.

Such protections are based on mayoral Executive Order 41, which establishes limits on the collection and release of confidential information, including immigration status, sexual orientation and status as a victim of domestic violence.

The order, issued by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2003 and reissued by Mayor Bill De Blasio, states that “No City officer or employee may disclose confidential information unless such disclosure is required by law,” adding that no City employee may disclose immigration status information unless the employee or their agency suspects an individual “of engaging in illegal activity, other than mere status as an undocumented alien.”

Key to understanding the threat that changes at the federal level mean for local government is the interpretation of existing federal law, which President Trump and conservative lawmakers maintain has the power to compel localities, as well as individual employees, to disclose the information protected by EO 41.

Reading code

Trump’s January 25th executive order on undocumented immigrants threatens funding cuts to so-called “sanctuary cities” based on Title 8 Section 1373 of U.S. Code. But Pratheepan Gulasekaram, a Santa Clara University law professor who specializes on the relationship between federal and local governments in immigration enforcement, says that bit of code lacks scope and authority.

“Right now, under federal law as currently written, I don’t see the ability to leverage or exert enough pressure to get localities or local agencies to comply with things they don’t want to comply with,” Gulasekaram says. “1373 has not been litigated and the federal government has not used it as a lever. There are no penalties or remedies for violations written into the law. It’s an open question whether 1373 is even constitutional or lawful in the first place.”

The first portion of 8 U.S.C 1373 states that “Notwithstanding any other provision of Federal, State, or local law, a Federal, State, or local government entity or official may not prohibit, or in any way restrict, any government entity or official from sending to, or receiving from, the Immigration and Naturalization Service information regarding the citizenship or immigration status, lawful or unlawful, of any individual.”

Though proponents for close collaboration among municipalities and federal immigration enforcement project 8 U.S.C. 1373 as a broad provision, Gulasekaram says “their position will almost certainly lose” when tested in court because the city could employ various arguments against the code, including invoking the law’s own “nothwithstanding” clause.

“The city might maintain that 1373 doesn’t apply to it by virtue of its prefatory clause ” he says. “That is, they might argue that EO 41 is an ‘other provision of local law.'”

In an analysis of Trump’s executive order on the deportation of undocumented immigrants, University of Virginia immigration law professor and former White House counsel David Martin also minimized the scope of 8 U.S.C.1373.

“Section 1373 is actually a rather modest federal law, which does not force broad cooperation on unwilling states or localities,” Martin wrote. “It merely says they may not forbid their employees from communicating immigration-related information to federal officials. The state or local law enforcement agency doesn’t have to collect or provide any requested information itself, and it can even remind its employees that they aren’t obligated to send such information. Section 1373 has been upheld by a leading circuit court case, but it has not been ruled on by the Supreme Court. It might still be vulnerable to a challenge under the Court’s anti-commandeering doctrine, which provides that the federal government may not dragoon states into enforcing federal laws.”

Safety in shelters

New York Coalition for Immigration Legal Services director Camille Mackler says the policy of not asking an individual’s immigration status remains an effective tool for resisting ICE incursions because the federal government cannot compel city agencies to collect immigration information in places like the homeless services system.

“As long as immigration status is not recorded then ICE won’t have probable cause to go into shelters,” Mackler says.

The Mayoral Executive Order prohibits immigration status inquiries except when determining program, service or benefit eligibility or the provision of City services. The city’s right-to-shelter mandate means that anyone qualifies for shelter regardless of origin or residence. However, the immigration status of individuals who utilize DHS shelters is sometimes noted by outreach workers and intake shelter case managers who are trying to determine an individual’s eligibility for housing programs.

This also enables DHS and its providers – the organizations that operate shelters funded by DHS – to coordinate services and track individuals throughout their stay in the shelter system.

Last Thursday, just over 60,000 individuals utilized DHS shelters and immigrants – who make up more than a third of New York City’s population – comprise a significant proportion of that shelter population, according to published reports.

Undocumented immigrants barred from federal, state and city housing programs like Section 8 or Living in Communities (LINC) Rental Assistance often turn to shelters as their lone option for consistent sleeping quarters. Meanwhile, some undocumented immigrants with diagnosed mental illnesses do not qualify for placement in supportive housing – permanent housing with on-site social services – and thus remain stranded in shelters.

Even when the city does record immigration status information, they are “extremely unlikely” to comply with federal government requests, especially given the vague interpretation of Trump’s executive order and existing immigration law, says Lenni Benson, a professor at New York Law School and director of the Safe Passage Project for undocumented immigrant youth.

“The importance of the details matter,” Benson says. “Until the federal government articulates rules and programs and specifics, I don’t think people should stay away from safe housing because they are afraid the city would have to turn over their records.”

“The people who need the essentials in life such as going to the hospital, going to school or going to the shelter, in New York City can do that with really good security that they’re not going to be apprehended,” she adds. “The city will not [hand over information] voluntarily or quickly. They’ve been really clear about that.”

DHS Spokesman Isaac McGinn said the city would not share immigration status information with the federal government.

“As always, we protect the privacy of any and all confidential client information shared with DHS for the purposes of determining program, service or benefit eligibility or the provision of city services,” McGinn said in an email.

ICE told City Limits that they have not focused on detaining immigrants at homeless shelters.

“U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has not conducted any enforcement actions in or around homeless shelters, nor does it maintain an ongoing relationship with the NYC Department of Homeless Services,” said ICE spokesperson Rachael Yong Yow in an email.

Unsettled law lingers

In 1996, the federal government passed a law stating that a locality could not prevent an employee from reporting undocumented immigrants. Though Mayor Rudy Giuliani fought it, the City lost when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the federal law.

In 2003, Bloomberg’s Executive Order 34 did enable the City to collaborate with federal immigration enforcement for the first time since the Ed Koch administration in order to comply with federal law.

A few months later, Bloomberg issued Executive Order 41 to prohibit disclosure of information pertaining to several other vulnerable classes in addition to undocumented immigrants. The broader directive enabled the order to withstand federal pressure because it prohibited disclosure to anyone, not just the federal government, Rutgers Law Professor Bernard Bell says.

Bell says he believes that the Appellate Court’s 1999 decision and 8 U.S.C. 1373 are both unconstitutional but have yet to be tested in higher court.

“There is a strong Tenth Amendment anti-commandeering argument that requiring localities to provide information and interfering with their control over their own employees is unconstitutional,” Bell says.

Despite the relative protections upheld by the city, anti-immigration policies and a xenophobic atmosphere throughout the country affect immigrants here, says Ernie Collette, an attorney with the nonprofit law firm MFY.

“A lot of immigrants in the shelter system have protections because they’re in New York City, but that doesn’t diminish the fear that they could be removed,” Collette says. “We have to make sure we really do back up what we say by protecting immigrants who are in the shelter system so they aren’t choosing between sleeping in a shelter or sleeping in the street because their rights are infringed.”

Following ICE raids on Central American families throughout the country in January 2016, the Mayor’s Office of Immigration Affairs released a statement affirming the city’s commitment to safeguarding residents’ immigration information under Executive Order 41.

“City agencies are forbidden by Executive Order 41 to ask about immigration status unless it is necessary to determine eligibility for a benefit or service,” the statement read. “If an individual does share his or her immigration status or other confidential information with city employees, city employees may not report this to anyone, except when it is necessary for the investigation of an illegal activity, other than mere status as an undocumented immigrant.”

City Limits coverage of housing policy is supported by the New York Community Trust and the Charles H. Revson Foundation.

2 thoughts on “Shelter System and Other NYC Services Should Be Safe for Migrants, Experts Say”

Joe Bialek from Cleveland, Ohio, writes to City Limits:

My grandfather Albert Joseph Bialek came to the United States from Poland

{Galicia} in 1910. Per the Ellis Island website he boarded the ship Kaiser

Wilhelm der Grosse in Bremen, Germany {formerly Prussia}. He had just

completed his service in the Austrian Army. Poland at that time was divided

into three spheres of influence by Austria, Prussia and Russia. Upon being

discharged he returned to his father’s farm. Officers from the Austrian

Army made an attempt to reenlist him but tradition dictated that he could

remain at home so long as he was sorely needed on the farm. Immediately

after the officers departed Albert’s father gave him his brother’s travel

documents and instructed him to immigrate to the United States. His father

knew that war was coming and he didn’t want to lose his son to it. It took

me longer to locate my grandfather on the passenger list because I had

forgotten he was traveling under the name Jan and not Albert. Given the

fact that Albert entered the United States under the name Jan Bialek and

later burned his immigration papers it is evident he was by definition a “illegal

immigrant.” He went on to become a very hard-working brick mason and

law-abiding citizen raising 12 children with the help of his Polish wife

Mary {nee Mazan} and the rest {as they say} is history.

Just as Cleveland {Ohio} is a city of neighborhoods so is the United States

a country of immigrants. In fact all the major cities of America {at one

time} served as incubators for immigrants to not only become accustomed

to the ways of this country but also to intermingle with each other {often

prohibited in their native homeland}. It’s a shame that the inner cities were

handed over to the absentee landlords following World War ll. Just imagine

how much stronger and united our country might have been had this unofficial

tradition continued. Gentrification is not the answer. Preventing immigration is

not the solution. Intense vetting is acceptable during these challenging times

but to unfairly deny one person access to the United States makes us all orphans

again. As a popular song goes: “let me in immigration man.”

Pingback: Lenni Benson, Safe Passage Founder, Quoted in The New Yorker and City Limits - Safe Passage Project